-> Found at the HathiTrust Digital Library site. Or direct to the First Page of the text.

July 31, 1920 (pages 149-150)

Source had no images, so I used some images from my collection.

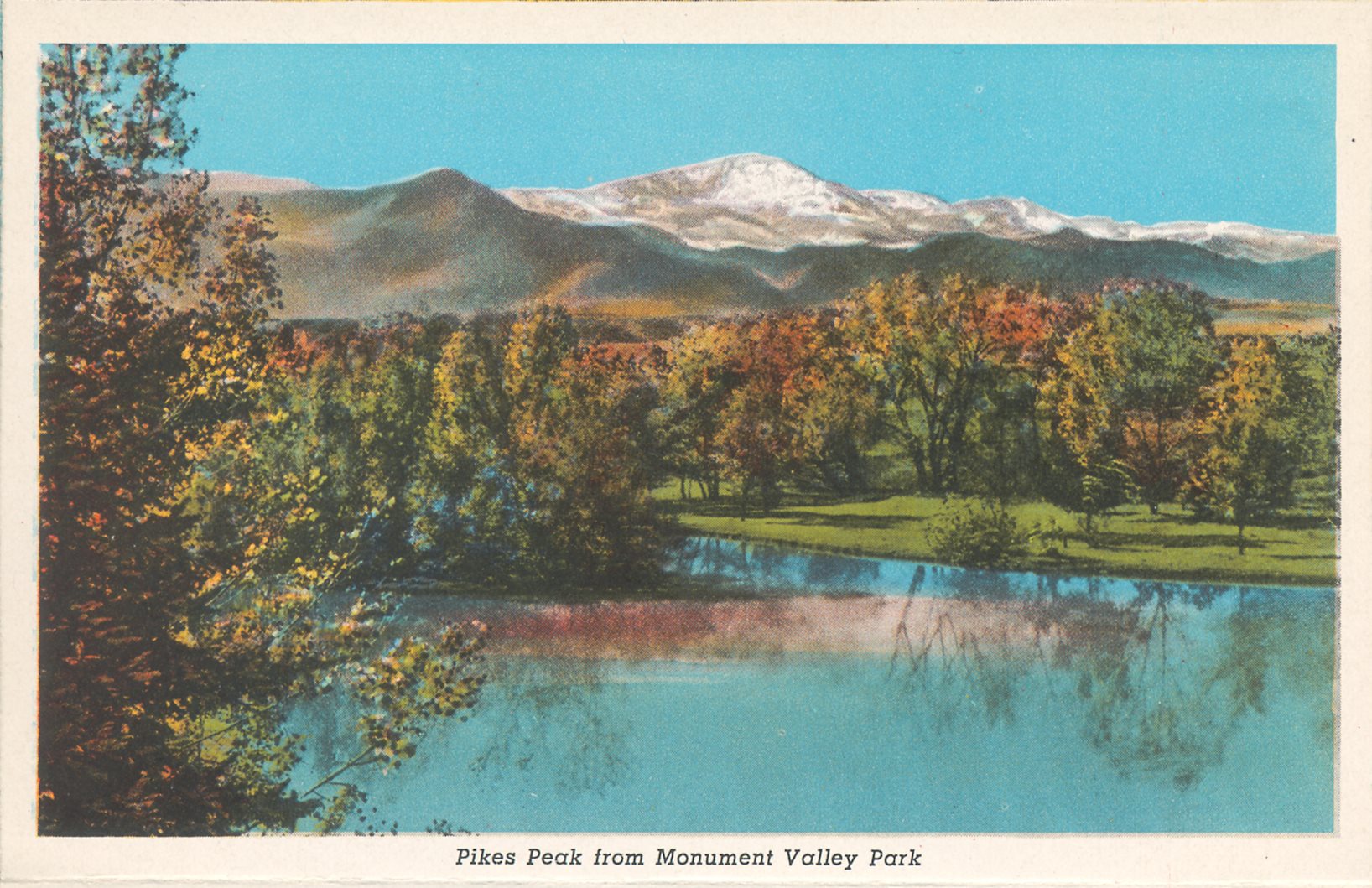

On July 14 the centenary of the first ascent of Pike's Peak was celebrated at Colorado Springs. The event provokes a retrospect. The soldier explorer, Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike, who discovered and named the mountain, was not the first to ascend it, that honor being claimed by Dr. Frank James, a member of an expedition under Major Long, who has likewise given his name to one of those hoary sentinels that look down upon the Prairie around Denver. Dr. James ascended Pike's Peak on July 14, 1820, starting from Fountain creek, la fontaine qui bouille, the spring that bubbles, as it was called by the French trappers long before Manitou Springs came into existence.

In honor of the first ascent, Major Long named the mountain James Peak, but as the earlier trappers and plainsmen had called it Pike's Peak as far back as 1810, this name survived, and Dr. James conferred his name upon a peak to the north, not far from that which was named after his chief, overlooking Boulder and Estes Park.

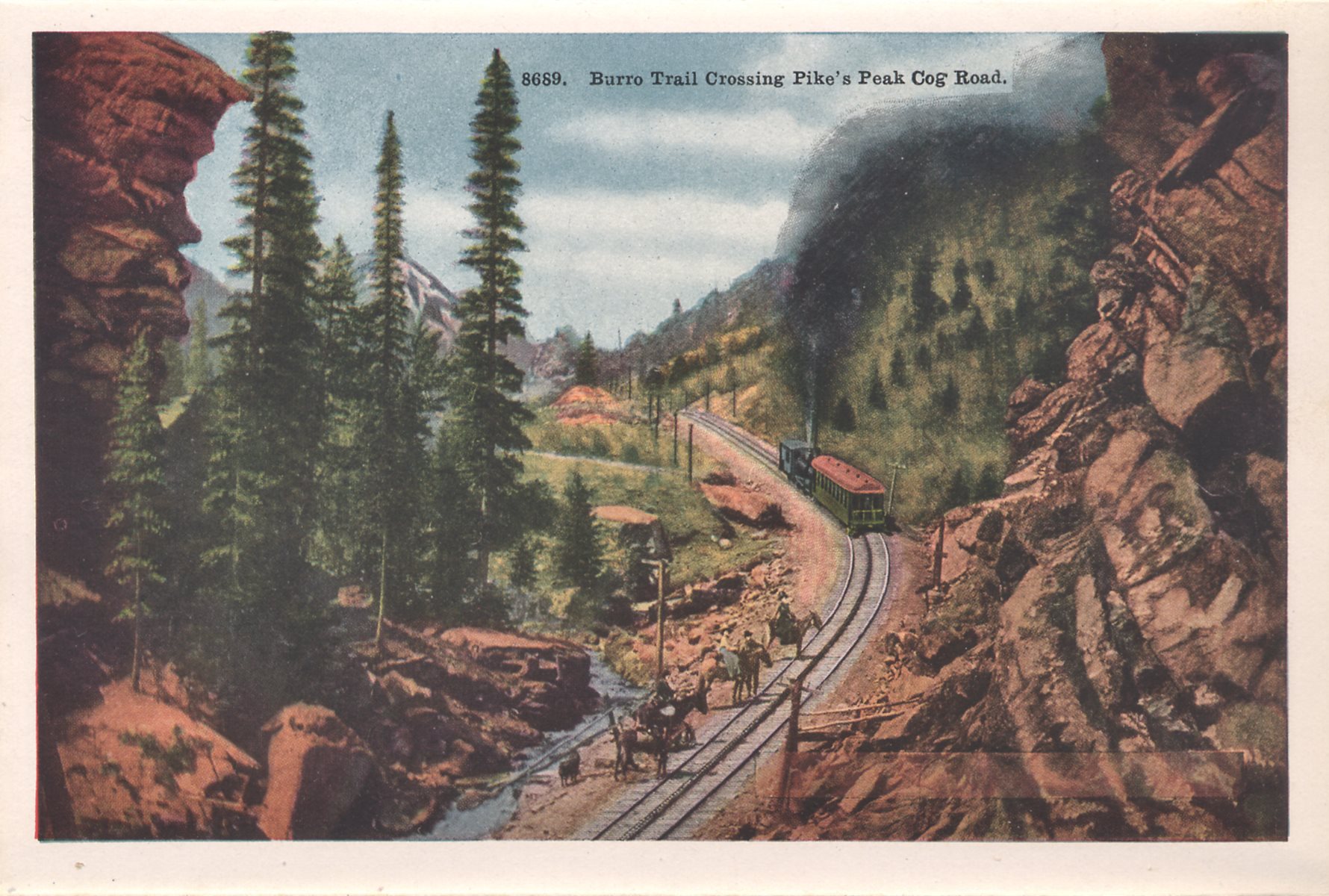

Since then a bridle-path, a wagon-road, a railroad, and an automobile road have been built successively to the summit for the benefit of the thousands of tourists that go thither every year.

A caterpillar tractor reached the summit last year and shortly thereafter an aeroplane sailed over the mountain, so that all the fascination of aloofness and loftiness has been taken from poor old Pike's Peak, but the essential romance remains.

In the early years of the last century the snowy crest of this granitic massif served as a beacon to the voyageurs and explorers who preceded the advance of civilization westward; in 1849 a party of Georgians, led by the Russell brothers, camped on Cherry creek, near the present site of Denver, on their way to Downieville, California.

In 1858 some of the members of this party returned to Colorado and uncovered the gold veins of Clear Creek and Gilpin counties. In 1857 a financial panic had broken the moorings of thousands of enterprising spirits and had incited a wave of popular migration westward across the prairies until it broke against the ramparts of the Rocky Mountains. In their progress across the plains the leaders riding in front of the wagon trains would seek with shaded eye for the first glimpse of the beacon mountain whose white crest on the far horizon gave promise of the land of gold.

'Pike's Peak or Bust', the motto of the adventurers of 1857 and 1858, sounds but mock-heroic in our ears, yet it expresses something of the mingled humor and daring of the men who pierced the unknown wilderness which was then the borderland of the Territory of Kansas. Thus the immigration that marked the birth of Colorado's mining industry was called "the Pike's Peak excitement"; but it expressed a delusion.

No noteworthy discoveries of gold were made at that time in the canyons or on the hills surrounding the peak. Important finds of gold and silver ore were made about 70 miles northward, under the protecting shadows of Long and James peaks. Although mines were started in many parts of Colorado during the succeeding twenty years, the silence of the Pike's Peak region remained unbroken. The cattle grazed on the sunny western slopes while towns and railways were being built amid the foothills of the eastern approach, but the prospector found nothing to justify the tradition of gold in the granitic battlements that rose above the line where the pines ceased to climb into the snowfields.

Suddenly, in the spring of 1884, rumors came of a great discovery of gold ore on the southern side of Pike's Peak. During the darkness of an April night a horde of prospectors stole swiftly away in obedience to the vague hints that had been scattered among the saloons of Leadville and the neighboring mining camps. Each party aimed to be first on the ground. The dawn of the next day found an excited crowd of four thousand men gathering at the foot of a pine-clad slope.

This became known as the Mt. Pisgah fiasco. Among the hills, which like a flock of sheep cluster at the southern base of Pike's Peak, there is a dark cone standing in solitude above its smaller brethren. This is Mt. Pisgah. In 1884 the miners who rushed thither could find no gold save in the prospect holes made by the first locators. Salting was suspected, the man who had instigated the rush had decamped, an accomplice was caught with a bottle of yellow stuff in his pocket. It was not whisky, but its quondam antidote, the chloride of gold.

Angry feelings found vent in threats of lynching, but in the failure to lay hand on the real perpetrator of the fraud, the affair was turned into a big picnic and a general drunk. A little digging had been done, one or two veins had been uncovered, but the poverty of the ore only added bitterness to the general disappointment. The prospectors disappeared as quickly as they had come.

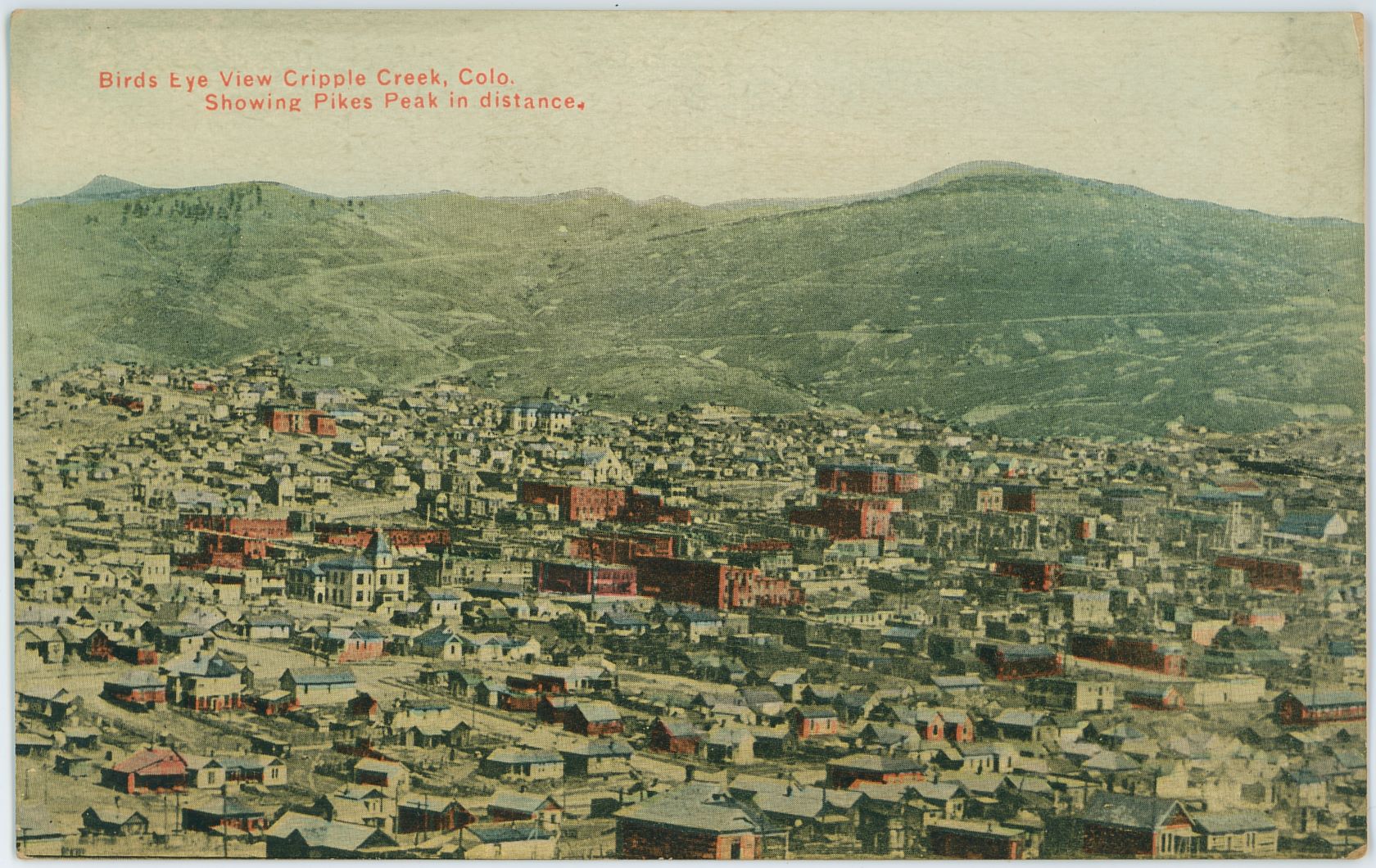

The hillsides resumed the quiet aspect of the cattle range for which they seemed best fitted. Pike's Peak was no mining district; it was left to the cows and the tourists. Nevertheless within ten years Mt. Pisgah overlooked the very streets of the town of Cripple Creek with its 20,000 inhabitants, and on the surrounding ridges the smoking shaft-houses bespoke a long series of rich mines.

The lodes of Cripple Creek were discovered in 1891, seven years after the Mt. Pisgah fiasco. During the interval prospectors had wandered over the hills from Colorado Springs and Florissant; indeed, it is said that a shallow shaft, dug by the pioneers even before 1884, was found just above the site of the Victor mine, which was one of the first to rise into importance during the early 'nineties.

Some of the cowboys employed by the cattle-men did a little desultory prospecting after the rains, when float is easy to detect. Among these was Robert Womack, who discovered the vein, in Poverty gulch, on which the Gold King mine was based.

That was in 1888 or thereabouts; in February 1891 he showed his find to E. M. de la Vergne and F. F. Frisbee, of Colorado Springs, both experienced miners.

Then came Stratton's discovery of the Independence on July 4, 1891. That event marked the birth of Cripple Creek, which two years later, in 1893, attracted thousands of miners thrown out of work by the collapse of the silver market. In 1891 Cripple Creek produced $2060; in 1898. $13,507,349; in 1900, $18,147,081.

The tradition of Pike's Peak was fulfilled.