-> My Collection, Also found at the HathiTrust Digital Library Site; Link to First page of article (at bottom of page).

I procured the coloring of the images.

HIGH up on the crest of a mountain in the Rockies there is a little huddle of houses. Not in the least like the picturesque Alpine villages, with their thatched roofs and time-softened tones, but garish and "beastly prosperous," as Matthew Arnold found Chicago.

Garish, in that a good part of the village is constructed of red building paper; prosperous, because every man willing to work earns four dollars a day, working only eight hours.

The location of human habitations depends largely upon what the surroundings may be made to yield. Four years back all the billowy country lying under the eye of Pike's Peak was tenanted mainly by the skulking coyote, the highsailing eagle. A few cattle pastured in the irregular valley down which Cripple Creek crept, sluggish and discolored with adobe clay.

The only human inhabitants were a few cowboys. Ten years before, in the time of Leadville's excitement over the discovery of Little Pittsburgh, a schemer planned to make a fortune here. He "salted" a hole upon Mount Pisgah - that is to say, sprinkled it with gold dust - and all El Paso County went daft.

The trick, though, was soon found out, and the gold seekers dispersed. Yet in 1893 that same prospector, patiently delving among the rocks, found the wonderful veins of gold that are Altman's reason of being. The veins are slender and winding as a ribbon.

Curiously, they are richest where most drawn out. Their richness may be guessed from the fact that a single mine, and that not the largest in the camp, shipped in the month of December, 1894, over thirty-five thousand dollars in gold, of which amount twenty thousand represented the month's clear dividend.

Of course the gold discovery brought the usual stampede. When it was established that the pay streaks encircled Great Bull Hill in the most surprising fashion, men began to think it good to live there. The result is a human eyrie clinging to the pinnacle of the mountain and rejoicing in the name of Altman.

It is certainly the highest incorporated town in Uncle Sam's domain, and makes a claim of being the highest in the world - though the claim is disputed by a perky village of the Andes. Altman folk, however, are quite sure they are nearer Mars by at least a few hundred yards.

Architecturally the place has not much to boast of; but that is not surprising when you remember that it was built in six weeks. The Westerner is a person of dispatch. He has not time to waste on bow windows and fancy porticoes. Instead he stacks up hewn spruce logs into one big sweet-smelling room, brings in his wife and babies, and lo ! he is at home.

Altman has neither graded streets nor cable cars, but it does have electric light to show off its crudities even at night. The projectors of it thought of nothing beyond housing their workingmen. Incidentally they achieved much more, for some of the grandest pictures possible are framed by its narrow windows. We seem to overlook the whole world - a strange, high, windy world, of white peaks and whiter slopes and duskily shadowed dippings; of dells and dark spruce forests and magically extending sky line.

We have three seasons. A bright boy from the East says they are "winter - and July and August." But what more can one expect at an altitude where pansies refuse to grow even under glass - where the boiling point of water will not cook beans or potatoes?

There is no spring. If she comes at all, the coy season, it is but to hover a moment on the mountain, counting the odds against her - the sunken coves that seem to hold storm winds asleep, the vast uplands numb in the grip of frost, the black-browed Peak frowning down upon it all - then go sighing away, halting it maybe for a peep in some sheltered valley that instantly quivers into new green life.

Summer comes tardily, with chills of sudden sleet, and quick, gusty snowfalls. Yet the quaking asp shakes out her brown tassels, the spruce forests and the pines thrill with sap to their new green tips. Then we know the snows are past. A little while, and the sleet softens into rain, wind flowers flutter on the hills, and like a happy dream the good season is with us.

It rains in the mountains as it does nowhere else on earth. The fall is a deluge that sets torrents running everywhere. And nowhere else I am sure does the lightning flare so brilliantly, the thunder bellow so hoarsely and terribly, as in the summer of our highlands. Throughout July and August, until mid-September in fact, there is a riot of green things over this upper world.

The leaves shake out in mad gladness inexpressible. One who has not seen the mountain aspen can scarcely imagine its beauty, or upon what lightly quivering stems its leaves dance and whisper through the time of sunshine. Underneath are the wild flowers, so strangely brilliant, so sturdy, so beautiful, I dare not let myself discourse of them if I am to leave space for ugly Altman.

Frost comes in mid-September. Ten days later we are in fairyland. It is a golden world - we have only tones of yellow - pure gold, chrome, ripened corn, buff, golden bronze - all in exquisite gradation, and in contrast more exquisite with the constant winter greenery. Of course it does not last - that is the worst of all fairylands.

But we can scarcely mourn for it, since it has taken us on to long bright days, when the far hills are steeped in amethyst; when the sun rides on a sea of sparkling blue; when the new moon comes early above the old Peak to show as a golden horn against the night sky's purple velvet.

Then, too, the wild raspberries ripen on the hills, taking from sun and mountain shale a rare wild savor to delight the gods sylvan, if any such there be.

Swiftly—all too swiftly—the bright days pale into the cold of winter. It is long and bitter. The Peak puts on his cloud mantle woven of vapors brought him by winds from the four quarters. But the strong wind comes out of the west.

His home is the Pacific, and every tree upon an unsheltered slope bears mute witness to his fury. He seizes the cloud and sifts from it a hail of bitter crystals upon the face of all the mountain land. Woe to man or beast without shelter at such a time ! The burro is the only animate thing which can brave one of these snowstorms.

He makes for any pretense of shelter, bows his back, throws forward his plentiful bang and goes calmly to sleep as becomes one of his philosophy. He was born to this - nothing better ! Why, then, should he quarrel with fate ? Most likely he came into being upon just such a day - grassy meadows and sweet waters he knows not - hence his contentment with a meal of tin cans, with a bit of gunny sack by way of dessert.

The region has a human type as characteristic as the burro. It belongs to the genus nomad, and usually to the species miner. Its tents are pitched always within hail of the last strike. It contributes generously to Altman's population; a population likewise variegated with saloon keepers - in the vernacular mixologists - "tin horn" gamblers and faded soiled doves. Naturally there is the most utter scorn of convention.

In this city in the clouds one can be as wicked or as pious as one pleases without in the least disturbing one's neighbors. Taken in bulk, the men have a sort of swaggering pride in their own grotesqueness both of appearance and of speech.

The miner wears invariably a juniper and trousers of blue denim. He carries a dinner pail in one hand, in the other a peculiar sort of candlestick. It has a strong sharp prong by which it may be thrust into a crevice of rock. The same prong makes it a deadly weapon either for attack or defense if by chance need arises.

His dwelling, like himself, has a nomadic tendency. It is built, indeed, with an eye single to later journeyings on wheels. Indeed, a thoroughbred Bull Hill cabin is a hopeless gadabout. In some cases the roving instinct is so developed, cabins are moved from one side of town to another. The correct thing, however, is, while you are about it, to move to another town.

They have big hearts and generous, those same miners. If you doubt it, hear this tale of a benefit ball in our elevated borough.

It was got up for a miner who had "gone and got hisself blowed up, foolin' with a hung shot," as the managers expressed it.

A hung shot, be it understood, is a cartridge which fails to explode after being set in place. It is delicate and deadly work, for which money cannot pay adequately, and usually undertaken as a matter of professional pride as much as of necessity.

This particular hung shot came near costing the man who touched it off his sight. His eyes were so fearfully burned that it was necessary to give him three months of treatment in a Chicago hospital.

Every man, woman and child in Altman went to the ball. Babies were, in fact, so much in evidence, a stranger would have inclined to the belief that a number had been specially chartered for the occasion. But he would have been mistaken - all were local productions who divined with infantile sagacity that they had a night and a right to squall under their own vine and fig tree.

Laundry work pays in Altman as in other mining camps. A smart and lucky woman easily makes her six dollars a day. Caste is not unknown among the dames of the suds. Laundry Belle, who owns the shack she occupies on Main Street, holds her head ever so much above Mrs. Dooley, who has nothing but a tent and toils over miners' flannels - especially since the luckiest prospector in camp led the grand march at the ball with the Belle upon his arm, while Mrs. Dooley and her unsoaped brood gaped undistinguished at one side.

Of course the ball had its aristocratic clique. It was made up of the wives of the shift bosses from the various mines. Mighty fine they were, in Chine silk, white slippers and white gloves.

They huddled exclusively in one corner, keeping jealous eyes upon their dancing cards. It was intensely comic to see the frozen stare with which one of them paralyzed a good-natured forgeworker from her husband's mine. He was a stout fellow, who had made a heroic effort to look smart, and had only succeeded in washing off streaks of the smithy grime. He asked for a waltz. What he got was harder than a stone.

The town seamstress was there in the glory of an Eton jacket—the which festive garment has just reached this altitude. "The whole shooting match" has fallen victim to it. The seamstress had black velvet over what the miners call "a b'iled rag," that is to say, a white frock. Mrs. Dooley's was lightish corduroy, and in her judgment smartened noticeably her faded brown cotton alpaca.

The Cousin Jacks turned out to a man. Let me explain that Cousin Jacks are Cornish miners, and very plentiful hereabout. One whose hair was of the true carrot tinge they told us had been a dancing master back in Cornwall. His partner was small and meek-looking - a waiter girl from the Smuggler boarding house. She was terribly embarrassed by finding herself unable to keep up with the pace he set. His was truly a fantastic toe, though it lacked much of being light.

A pretty creature, rosy as rosy-fingered morn, sat alone, a little way from our party. She was distinguished by not wearing the pervading Eton jacket, so we were certain she had come from the other side of the Peak, where fashions are three months behind Altman. She had a sleeping baby, as fat and rosy as herself, cuddled in one arm. With the other hand she beat time disconsolately to the music.

"Do you like to dance?" I asked her, tentatively.

She gave an emphatic nod, saying: "Now don't I ! Jest—— But I woon't git the chance. My man he don't dance, and he woon't keep the baby ! I say it ain't much fun listenin' to music when you know you cain't shake yer foot. They're playin' the pokey now. O-oo ! Don't I love it ! I'd 'bout as soon be licked as ter come here an' look at the rest an' not git ter dunce the pokey."

"You shall dance it," I said, holding out my arms for the sleeper.

In two minutes she was heel-and-toeing along-side a tall Dutchman.

"Look at that fellow," some one said at my elbow. "You know, after the strike last summer, the superintendents had orders, when the mines re-opened, to employ no man who had been conspicuous in the riots. Well, one day this fellow presented himself to a superintendent I know, and demanded a job. 'What claim have you ?' my friend asked. The Dutchman struck an attitude of conscious power.

'I ought to be gif do job ef any man vos,' he protested. 'I haf hear der vighting ish to be count, and I vos in efery scrap dey did haf.'"

An odd couple followed the Dutchman and the polka enthusiast. The man was very tall, with an evil face and a disfiguring stoop. It was not strange to hear that he was suspected of many dark deed?, but unaccountable that he had thus far escaped Judge Lynch and rough-and-ready Western justice. His partner was likewise tall, and had been magnificently handsome.

Now there was something ghastly in the livid, sunken, twitching throat left bare and exposed by her low-cut pink bodice.

All the air was heavy with cheap loud odors. The good company had been lavish of perfume and pomade. Then, too, everybody was chewing gum. One could almost believe a gum peddler had stood in the door and found a customer in each of the merrymakers. But what were such trifles beside the solid fact of money enough in the treasurer's hands to insure the disabled man his three months in the care of a specialist ?

Since the miner's war of last summer Altman children have a new and favorite game. "Miners and deputies" they call it, and it is needless to add the miners get the best of it. The Western Federation of Labor has things pretty much its own way here. It dictates with impunity when and how a man shall work his own property. Altman is, indeed, the ideal home for such a body.

Here they can throw up a fort, garrison it with a handful of miners, and might calmly defy our Uncle Sam's army if it did not bring along with it plenty of Gatling guns.

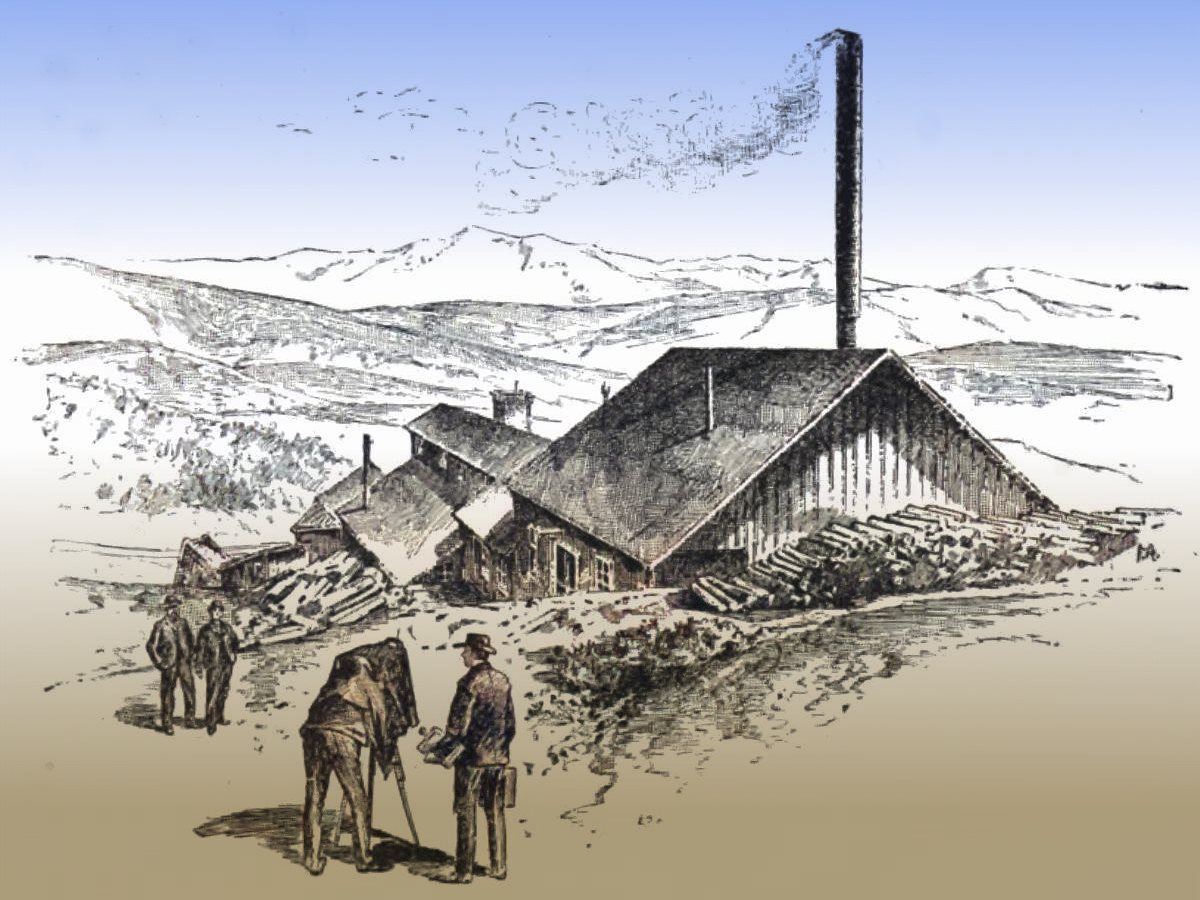

![Click for larger view, more info Zenobia Mine & Town of Altman. {Erroneous Called Buena Vista Mine]](/04library/images/frank-leslies-popular-monthly/1896-05-p543-crpd_zenobia-mine-colored_i-00193.jpg)