-> My Collection; No source to show as I've not shared/scanned the Mining Journal as an album.

But, here is a link to first page on Hathi Trust Digital Library website.

September, 1896 (page 59->60)

Source had no images, so I used some images from my collection.

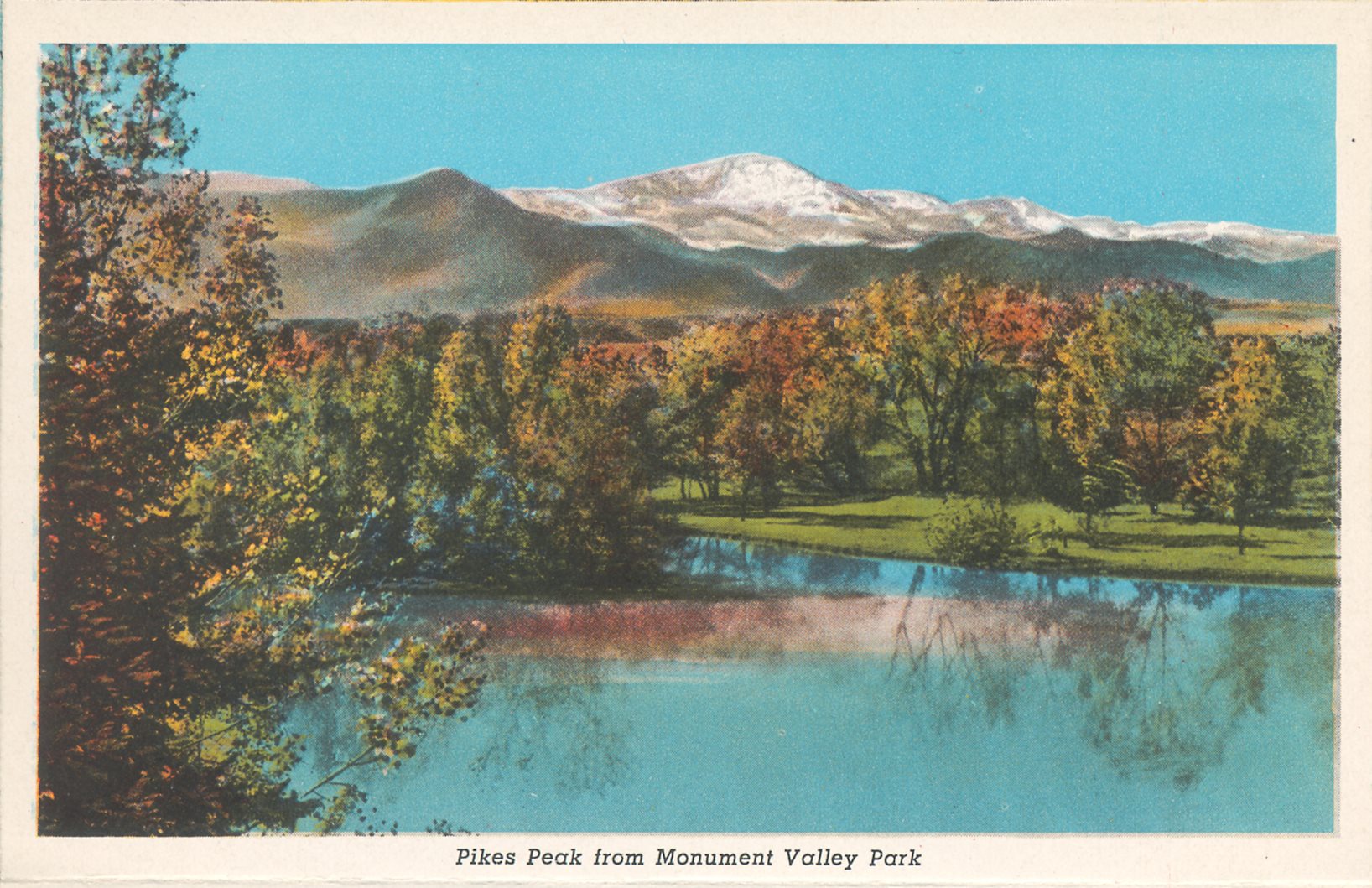

Pike's peak is perhaps the best known mountain of the Rockies. It was the goal of the early pioneers "in the days of '49" and was supposed by the visionary "forty-niner" to be an El Dorado which if once reached, riches were sure, hence his prairie schooner wore the title "Pike's peak or bust." Yet, singularly enough, of all the prominent mountains of Colorado this has hitherto proved one of the least productive in itself, though Cripple creek, which lies on its western skirts and is located on the same granite system and mass as the peak, might have realized some of the most visionary hopes of the forty-niner if the latter had only lit upon the locality.

But Cripple Creek is Cripple Creek and Pike's peak is Pike's peak, and there is no very strong connection between the two. Cripple Creek seems to keep its mineral wealth pretty well to itself and within the boundaries of its own phonolitic and andesitic eruptions, which do not extend far into the Pike's peak mass proper, and though of late the peak and its surroundings have been pretty well prospected, only a few ore bearing veins have so far been found, and no mine of large importance has yet been opened.

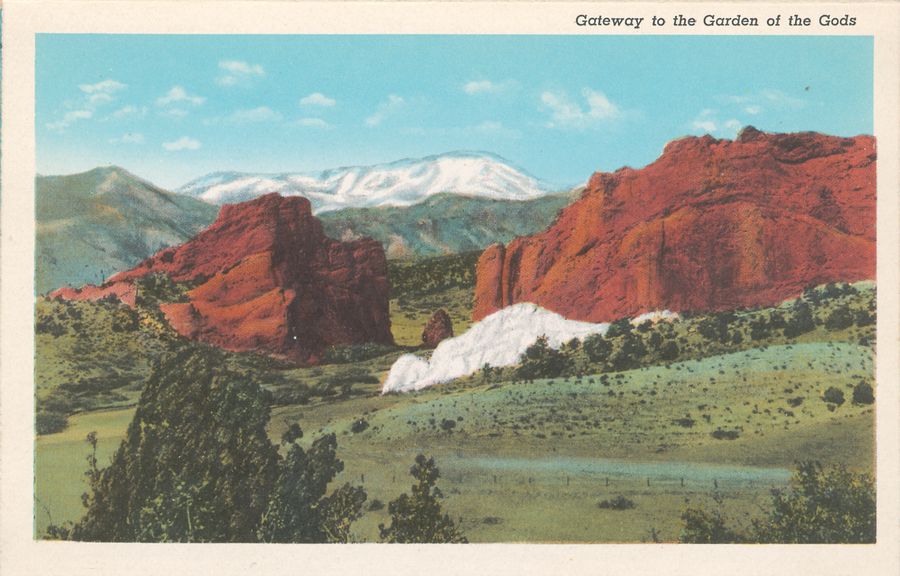

Pike's peak, or rather Pike's mountain, is a huge mountain mass of red and very massive granite rising from the wave-like zone of sedimentary hogbacks or ridges constituting the foothills bordering the great prairie. These ridges which follow one another like the crests of successive waves, represent the uplifted beds of primaeval oceans of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras from the Cambrian to the close of the Cretaceous. During a portion of these eras Pike's peak was doubtless a low granite island which at a later period was elevated into the rank of a mountain mass, dragging up with it and tilting the marine and other sedimentary bods that had accumulated through many ages along its flanks and base.

Subsequent erosion cut down and wore away these uplifted strata to the level of ridges and hogbacks and wore them into the grotesque and picturesque forms familiar to us on Glen Eyrie and the Garden of the Gods at Manitou.

Passing over this zone of wave-like uplifts we enter the granite itself. Just before the contact we find the Cambrian and Silurian and Lower Carboniferous sandstones and limestones the same as at Leadville and Aspen, but here unaltered by heat and not penetrated by eruptive rocks and hence without metal veins or concentration of ore bodies.

THE PIKE'S PEAK GRANITE.

The so-called red granite of the mountain is more strictly a red syenite or syenitic granite than an orthodox granite. Hornblende amongst its constituent minerals predominates over mica. The principal elements are a red orthoclase feldspar and a white or gray quartz. Locally, and as specimens, quite a number of other minerals occur in veins and seams, such as the beautiful bright green Amazon stone, which is a feldspar stained green by some kind of mineral solution ; with these, occur crystals of all sizes of smoky quartz, from an inch to two or three feet in length and as much as a foot in diameter, quartz crystals of dark transparent smoky tint; occasionally, but rarely, genuine pure topazes are found, some of the finest in this country.

The peculiar aluminium bearing mineral called cryolite is found locally in pockets, but not in commercial quantity or value. Garnets, tourmalines, beryls, and numerous other gems of more or less value are found in veins and crevices or washed down in the sands of streams.

The syenitic granite on the lower portion of the mountain is quite coarse and breaks up in a wonderful manner into coarse gravel. In the higher reaches and toward the summit the granite becomes finer grained and more porphyritic, i.e., the rock has a finer grained ground mass or paste of feldspar in which large individual crystals of feldspar occur, like plums in a pudding.

These crystals, by reason of their superior hardness, often stand out in relief from the surface of the rock, giving it a rough appearance. There appears to be here, as at Cripple Creek, two varieties of granite of different dates of eruption. An older and coarser variety forming the main mountain mass is cut by a newer and finer grained granite, the narrow dykes of which often stand out in prominent relief and long red veins above the older and softer species.

Another noticeable feature is a local schistose structure of the granite produced by "shearing" and faulting movements by which the rock is divided up into a series of parallel sheets along certain zones.

MINERAL VEINS.

It is mostly in the crevices of these shearing zones that what few mineral veins have so far been discovered, occur. These veins carry pyrite, assaying more or less in gold. Sometimes a very distinct vein is seen of pure white quartz, as a rule too white, nice, and pure to carry much, if any, of the precious metal. These veins may occupy fissures caused by jointing or cleavage planes, such as are common in most mountain regions, resulting from contraction or cooling of the mountain mass or from general upheaval.

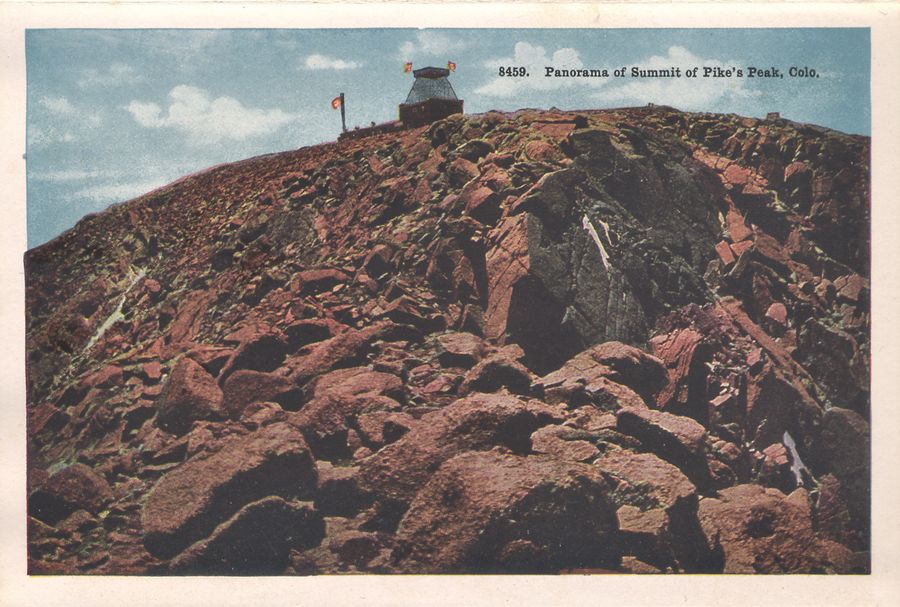

The granite of the Peak is exceedingly homogeneous and uniform and very massive, offering comparatively few cracks, crevices, or other weak places for ore solutions to penetrate. The upper part of the mountain is cloven by steep cliffs and hollowed out into punchbowls by glacial agencies. These expose the granite in large unbroken surfaces, and would readily show any prominent vein or ore deposit that might exist without the trouble of prospecting for it. But few of such veins have been found, and though some may be discovered of value, the mountain, as a whole, offers comparatively few inducements to the prospector or probabilities of its becoming at any time an important mining center despite its past mythical golden reputation.

DISINTEGRATION OF THE GRANITE.

One of the most remarkable features of the mountain is the rapid decay and disintegration of the granite into a coarse gravel, with which the slopes of the lower portion are deeply covered. The process of disintegration in all its stages is observable on all sides. The point of weakness, or the weak element in the granite, appears to be the black iron-bearing mineral called hornblende. The lustre of this is everywhere tarnished and rusted by oxidation, and the rocks are pitted with little holes where this constituent mineral has oxidized entirely put.

These cavities admit moisture into the rock and disintegration follows rapidly. First the feldspars go, then the quartz, and the rock passes into a loose gravel. A peculiar and common result of this disintegration is the forming of curious mushroom-like monuments of granite. A hardened rusty outer crust on top is eaten away and undermined from beneath, leaving a mushroom-like cap. It would seem that the water and moisture falling on and quickly shed from a smooth sloping or rounded surface of granite, oxidizes this crust into a hard and comparatively impervious material.

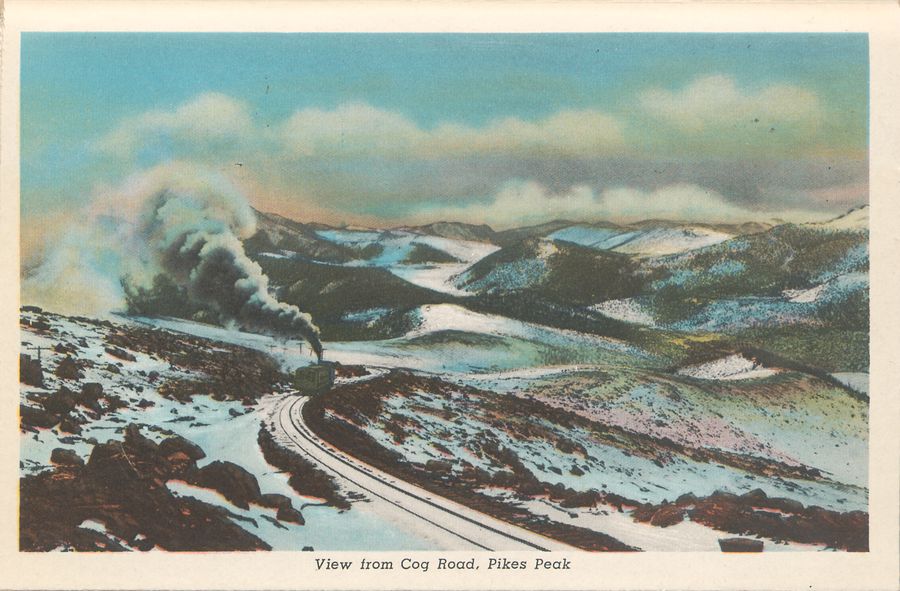

The elements then attack the rock from below and on the side most exposed to the prevailing winds and storms. This disintegration is most observable in the lower thousand feet of the mountain. Towards the top, a harder, finer grained variety of granite sets in and the top of the peak is an area of large broken blocks of fine red granite. These would seem to be broken up by the action of frost from the snow, which lies on the summit during several months in the year. Erosion, in past times, has been on a grand scale, principally through the medium of glaciers. The area immediately surrounding the peak, is honey-combed with deep punchbowls and amphitheatres, the bottoms often occupied by emerald lakelets.

These hollows were the homes and starting places of the glaciers, where they first accumulated as neve, or snowball ice, later passing by pressure into pure blue glacial ice and descending as ice rivers or glaciers through many deep and radiating ravines. At times the glaciers descended steep step-like cliffs over 500 feet deep ; as they bent over these, doubtless the ice sheets cracked open in crevasses above, whilst below, the ice planed and smoothed the granite into the rounded forms peculiar to glaciated regions called "roches moutonnees" or "sheep backs."

At other places in its descent it hollowed rocky basins, or threw dams of debris across the drainage of ravines in its retreat, which now are filled by beautiful lakelets yielding the water supply of Colorado Springs city. The track of the ancient glaciers is everywhere apparent by these signs, together with the banks of huge boulders which it left in its path as it melted. The erosion, begun on so liberal a scale by the glaciers, has later been carried on by streams, rain, snow and moisture.

THE FOOTHILLS AND HOGBACKS.

The foothill zone bordering on the base of the mountain celebrated for its remarkable scenic beauty and picturesque rock forms, as shown in Glen Eyrie, in the Garden of the Gods, and at Monument creek, has little attraction from a mining or prospecting point of view.

The Cambrian sandstones and Silurian and Carboniferous limestones are more remarkable for their wonderful caves and stalactites than they are ever likely to be for mineral wealth. True they belong to precisely the same series and the same geological ages as the silver bearing rocks higher up in the mountains at Leadville and Aspen, and it may well be asked, why are they therefore not metalliferous?

The answer appears to be the local absence of any eruptive rocks or of the influence of metamorphic heat, which seem inseparable from ore occurrence. The Cambrian rocks that rest on the old weather beaten granite shore line of the peak, red, white and greenish sandstones and limestones, are almost as unaltered by heat as in the days when they were deposited by the ancient seas, whilst at Leadville and Aspen these same rocks in similar relation to the granite are highly crystallized into quartzites and sometimes into marble, and are everywhere penetrated by fiery tongues, sheets and dykes of eruptive porphyry, which are totally absent from the region in question, and in fact, even in the great granite mass of the peak, despite its semi-igneous origin, we noticed but two well defined dykes of true dark igneous rocks other than the granites we have alluded to. Such a marked absence of igneous rocks is in Colorado an unfavorable sign for expecting mineral deposits.

As a receptacle for ore the limestones around the base of the peak present every convenience. They are traversed by innumerable joints, fractures, and bedding planes, which here and there have been enlarged by percolating waters, into considerable chains of caverns, but the ore bringer, or ore promoter, the hot porphyry, was not present. The tea cup is here but no teapot to pour out the tea. A lesson which shows us that it is not so much the rocks of any particular kind, or geological age, that are in themselves ore bearing and productive, as other circumstances outside of themselves that may make them recipients of the precious metals, principally local heat, metamorphism and eruptive activity.