-> My Collection; No source album to see. But, an online digital version can be found here on the Hathi Trust Library site.

(pages 147-154)

[Images used was not part of story]

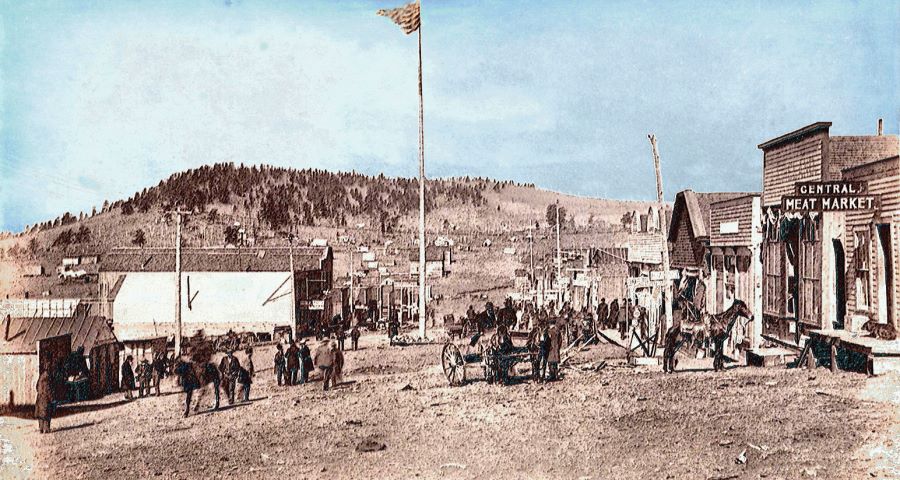

IN the earlier days of Cripple Creek—for Cripple Creek is yet in its early days—before the railroads which scented its riches had invaded its inner circle of hills, and before the great fire which ruthlessly licked up its ramshackle architecture had paved the way, so to speak, for the present more substantial and imposing city—one radiant September morning of that primitive epoch the Denver train rolled noisily up to the depot at Midland—the then nearest railroad point to the great gold camp—and among the passengers who alighted was a bright-faced little "tenderfoot," who stood irresolute on the depot platform and looked about her with a bewildered but half-amused expression in her soft brown eyes.

"I think this must be Miss Nellie Gray," said a kind-faced middle-aged gentleman, accosting her. "Dr. Dean asked me to look out for you. I am on my way out of the camp, but I can put you on the stage and tell the driver to drop you at the doctor's home."

"Oh, thank you," said Nellie, her face beaming.

"Here, Faro!" he cried, "hold that front place there. Got your stage ticket, Miss Gray? That's it; give it to this man. Now; don't you want to sit with the driver? Best place on the coach and less dust——"

"Oh, yes," said Nellie.

"Climb up on the wheel, then; I'll help you. Faro, take care of this young lady and let her down at Dr. Dean's."

"All right," drawled Faro, casting an eye of approval on his passenger and sprucing up in his seat.

Nellie sat perched high upon the old tally-ho, breathing the pure and fragrant morning air and drinking in the beauty of the mountain scene. She was fresh from a normal institute "back east" in Missouri, and was under contract to teach in the public schools of Cripple Creek; and—happily for her—there was a home for her there in the family of Dr. Dean, who had formerly lived in her native town. She was a pretty little thing, graceful and rosy-cheeked and with a habitual smile lurking about the corners of her mouth.

"I hope I won't be in the way here, Mr. Faro," she said.

"Not a bit," said Faro, gallantly. "Jest hold on tight when she rocks. Come, boys, wake up!" and the long whip whizzed through the air and flung out with a loud crack over the heads of the leaders. "Limber up, there, Moses; hey! you locoed bronchos, get up there into your collars!"

View of Hundley Stage with Cripple Creek in background, leaving over Tenderfoot Hill, c.1894.

View of Hundley Stage with Cripple Creek in background, leaving over Tenderfoot Hill, c.1894.

The long team of eight horses got into action. The pony leaders reared and plunged, the slightly heavier followers capered somewhat less alarmingly, the next pair simply marked time nervously, while the sedate wheel horses bent to their task, and the heavy coach, with its close to twenty passengers, besides baggage and mail sacks, was in motion.

A short, exhilarating gallop along a level stretch, and Faro pulled in the horses for the long, hard climb over the divide. He turned to his companion, after assuring himself that the men on the next seat were engaged in animated conversation—he had not failed to note a titter from that direction when Miss Gray addressed him—and in a subdued and apologetic tone took up the thread of remark where it had been broken by the necessity of getting under way.

"But my name ain't Mister Faro," he said. "My name's Mister Dunn—James Dunn. You see I'm jest called Faro for short."

"Oh!" exclaimed Nellie. She rather liked Faro; at least she liked to hear him talk, so she proceeded to argue the question. "But I can't see," she said, "that Faro is any shorter than your real name."

"That's so," answered Faro, abashed. "But, you see, all uv us drivers—that is them that's on the mail runs—is called somethin' or other besides our real names, an' they call me Faro on account of the game. You see I beat the game at Nolon's las' summer—won nine hundred dollars in one evenin'."

Nellie was considerably mystified. "You won all that money playing a game?" she asked.

"Yep," said Faro, grinning and slapping his knee in the pleasurable thrill of the recollection. "They couldn't whipsaw me no way."

"But you gave the money back, didn't you?" ventured Nellie.

"Yep," said Faro, with a long drawn sigh; "I give it back, an' some more, too—but not that evenin'."

The driver's immediate responsibilities served to divert him from that later and sadder recollection, and he gathered the reins tighter. They were now coming upon many freighting teams traveling in both directions. The coach was also beginning the ascent of a "zigzag" road up a slope which stood at about a forty-five degree incline. The road did not curve, but lay in acute angles, one plain above another, and it required skill to pilot an eight-horse team on those sharp turns. The dust, raised by the tramping feet of hundreds of horses, became stifling and almost blinding; and the track was narrow, with only an occasional widening for the meeting of teams. At almost every point where the road broadened, teams stood waiting for the coach to pass. The United States mails, both by law and by courtesy, had the right of way. But occasionally—principally on account of the dust which obscured a long vision—Faro found himself in a tight place, and only avoided a hopeless blockade or an accident by a dexterous handling of the reins and a judicious use of mild profanity.

They had almost reached the top of the slope, and were close to the last sharp turn, when they passed a wagon hitched to six robust mules headed in their own direction. The team was drawn to one side to make way for the stage.

"Hello, Robert!" called Faro to the driver of the freight outfit, a stalwart, dust-begrimmed young man who sat enthroned upon an enormous load of merchandise.

"Good morning, Faro," answered the young man, and lifted his sombrero as he espied the lady beside the stage driver.

"Awful nice chap," commented Faro, as he began to swing his leaders out for the turn; "he owns them mules an' he's got some mighty promisin' claims in the best location on Raven hill. Ain't worked 'em much yet, but he makes money freightin' and puts it all in the ground. He'll strike it there yet if he—— H———l!"

Faro had thus far managed to keep his vocabulary of profanity within less expressive limits. But there stood a freighting outfit, the wagon filled to the brim of its five-foot sideboards with ore, drawn up against the inner side of the road. The stage had made the turn, and to back around it was out of the question; and the ore team, with a four-ton load, was as powerless to retreat up hill.

"Why in thunder didn't you stay back there at the turnout?" roared Faro.

"Couldn't see yuh fur the dust," shouted the freighter. "Mebby I kin git up a little closter."

He drew his wagon a few inches nearer the bank. It now seemed that there was possibly enough room for the coach to pass, and Faro cautiously approached. He must get by somehow. He was a good driver, and a cautious one, but the mails must not be delayed. He piloted the coach carefully along until it was abreast of the freight wagon, and then it was seen that neither vehicle could advance without locking hind wheels.

The ground below the road was not very steep, and just off the edge of the bank, close to the front wheel of the coach, lay a small boulder. If he could throw his front wheel onto that, it would turn the coach so that the wagon could clear. He backed a little, took in the slack between the horses, threw his wheelers out over the bank and dropped the wheel onto the stone without seriously careening the coach. It would be an easy matter, after the freight outfit had taken its unwelcome presence down the hill, to turn the wheel horses sharply across the road and regain the safe highway.

Before the heavy wagon could be got well out of the way, however, the stone upon which the safety of the coach depended began to slip. Faro swore furiously, and vigorously jerked his horses in an attempt to regain the road; but it was too late. The stone settled inexorably, the coach leaned more and more, while those of the passengers who were not too frightened scrambled frantically out of the sinking ship.

Soon the coach lost its equilibrium and rolled heavily over, but was caught by a small tree before it quite lay on its side. The shock of contact threw Nellie, who had not realized the danger in time to act, straight out into the air, and she landed forcefully in the arms of the young man who owned the mules, who had left his team when he saw the impending trouble.

"Never touched me!" said the young man, jocularly, disengaging his clasp.

"Oh!" gasped Nellie, and then smiled entrancingly on her rescuer.

"Sit down on the ground and get back your breath," said he, "while I see if anyone is hurt."

Luckily, no one was injured; and with the help of the male passengers and the score of freighters who had congregated, the coach was righted and placed on the road. It was found to be fit for travel, and after the scattered baggage and mail sacks had been collected, the passengers began to clambor aboard.

"Let me help you to your seat," said the dust-begrimed freighter, re-approaching Nellie.

"I want to thank you first," she replied. "You probably saved my life."

"I am right glad I was there to break your fall," he said. "If you had struck the ground at the rate you were coming, it might have been serious indeed."

"I am sure of it," returned Nellie. "I don't know how to thank you properly. I—" and, at loss for words, she finished the more eloquently with a smile of such radiance that the young man stood as if transfixed with wonder.

"All aboard!" called Faro.

Nellie held out her hand to the young man, who was gazing at her with such frank admiration that she felt somewhat embarrassed. He took the little gloved hand tenderly, and, without removing his eyes from her own, said: "I want you to tell me your name."

"Oh!" exclaimed Nellie, confused and hesitating. "Why—yes—I will give you my card"; and diving into the pocket of her jacket, she produced a little purse and handed him a small white card with "Nellie Gray" engraved upon it.

"All aboard!" shouted Faro again.

"Thank you," said the young man. "Let me lift you up. Good-bye!" and the coach was off.

The freighter walked toward his team, with his eyes fixed on the small pasteboard between his fingers. "Just the thing!" he exclaimed enthusiastically, "just the thing! Wonder what such a little beauty is doing here. But of course she is only visiting. Or it may be that she is one of those newspaper women who come here to write up the camp—though she don't look it.

Anyway, it is not likely that she will stay in Cripple Creek. She will never know."

Home among the Pines.

Home among the Pines.

Nellie entered upon her frontier life with a brave heart. It was all new and strange to her, but a genuine home with old friends proved a great boon. Her duties were pleasant, and she soon came to take a real delight in the glorious climate and in the grandeur and beauty of the mountains. Christmas, with its joys—not unmixed with sadness for those who have loved ones far away—came and went its way, and her life moved on with little to break its peaceful monotony.

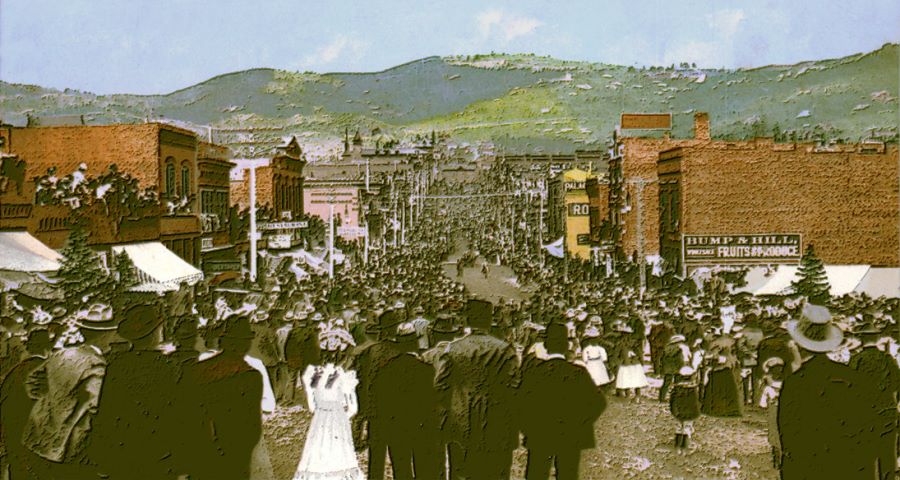

Looking West along Main Street, Cripple Creek.

Looking West along Main Street, Cripple Creek.

One afternoon—it was about five months after her arrival in Cripple Creek—her duties being over for the day, she walked down into the business portion of the town to leave a letter at the post office. She had accomplished her errand, and was walking westward along Bennett avenue towards home, when she was startled by hearing her name shouted from far up the street.

She stopped abruptly and looked wonderingly in the direction. The cry came again— a jumbled mass of words in which "Nellie Gray" were only intelligible. She soon divined that it was a street arab hawking the evening edition of the Daily Blast. But what could he be shouting about her?

The urchin was coming nearer. What was that? Did she hear aright? Was it something about "Nellie Gray raving?" Horrors! No, that was not it. It sounded like "Nellie Gray raising"— Raising what?

She strained her ear to listen. Merciful heavens! Her brain reeled and she would have collapsed had not another youngster— one with a more intelligible articulation—issued from a side street near her and she heard the message plainly:

"Evening Blast—all about the rich strike in the Nellie Gray on Raven Hill!"

"Hill!" gasped Nellie, recovering herself with an effort. "It was hill!"

Then she began to feel amazingly indignant. "I could almost choke that man!" she cried inwardy. "What right had he—whoever he is—to give my name to his old mine and allow it to be shouted about the streets in that outrageous manner!" Nellie was angry. She could scarcely suppress the tears. She walked rapidly homeward and burst in upon the doctor and his wife like a tragedy queen.

"Why, what on earth is the matter?" asked the doctor, as he caught sight of the flushed face and trembling lip.

Nellie hysterically told her story. Mrs. Dean was inclined to be sympathetic, but the doctor laughed. "Why, that's nothing," he said. "Scores of mines about here have girls' names. There's the Annie Lee, on Battle mountain—one of the richest in the camp—and I could mention quite a number among the less prominent mines. Many a prospector gives the name of his sweetheart to his most promising claim; and naturally enough, it seems to me."

"Well, this one didn't," said Nellie, blushing.

"Oh, you don't know," returned the doctor, chafingly. "There may be more Nellie Grays, you know. I used to hear a song about 'My Pretty Nellie Gray.' Colored girl, I think."

Nellie smiled a little.

"I heard about that Nellie Gray strike and saw a specimen of the ore down at the Palace hotel," went on the doctor. "It is wonderful. Free gold in quartz formation; and they say there is lots of it. I didn't learn who owns the claim, but he's a lucky fellow."

"Here is the paper," said Mrs. Dean, bringing it from the porch, where the carrier had just deposited it. The doctor glanced over the headings. "Here it is," he said. " 'R. W. Morrison'—that's the owner —'Steady and industrious young man —general favorite—Little development work on claim—owner obliged to depend on his exertions elsewhere to provide money for assessment work and patents—patents now nearly ready—strike made at only sixteen feet—good seam of high grade ore assaying as high as $23,000—owner refused an offer of $75,000 from Moffet this morning—active operations from now on—another bonanza,' etc., etc."

First School of the

First School of theCripple Creek District.

Nellie was by no means reconciled by the doctor's reasoning. But the subject was dropped, and the episode soon ceased to trouble her. The winter wore away; the school term drew to a close and her thoughts were occupied with plans for the future. She was assured of her position for the following winter, but she was undecided as to the intervening summer months. If she could procure some suitable employment there, she would elect to remain in Cripple Creek rather than incur the expense of a trip to her old home. The chances for employment suited to a young lady of Nellie's discrimination, however, were very meager, and she had about decided on the latter course when a circumstance occurred which changed her plans.

It was a couple of days after her school duties were over for the term. She was again walking on Bennett avenue, and again she heard her name shouted by a youthful vender of the news. This time the words seemed to bear an ominous ring, and her indignation was held in check while she listened breathlessly. The next shout was distinct: "Dreadful accident in the Nellie Gray mine! Owner thought to be fatally injured by a premature blast!"

Nellie was appalled. She felt no resentment now. It affected her as a matter of personal concern. She seemed to feel almost an individual responsibility. She hurried homeward, her thoughts intent on the man who lay mangled, perhaps dying, and who had met his awful fate in the Nellie Gray.

Dr. Dean reached home shortly after her arrival and called her into his study.

"Do you still feel resentment against the man who gave your name to his mine?" he asked.

"Oh, no! I have just heard about the accident. It is dreadful."

"You have been wishing that you had some employment during your vacation," went on the doctor. "If you care to take it, I can furnish you some which I do not consider will be unsuitable and which will pay you well. The owner of the Nellie Gray mine is badly injured; but I think he will recover, though he will probably lose his eyesight. He has been brought into town and is now at a private hospital quite near here. He is rich and there need be no sparing of expense in caring for him; but there have been so many accidents lately that there are not enough nurses to supply the demand. I want one in this case,—an assistant nurse to act under the direction of the professional nurse. The duties will be very light and will only be required in the day time. Will you help me out by undertaking this work ?"

"Yes," said Nellie, impulsively.

The following morning she accompanied the doctor and was installed in the sick room. The wounded man lay motionless upon the bed with his eyes tightly bandaged. Nellie felt an awe in approaching him.

"I have brought another nurse to help Mr. Lane take care of you," said the doctor.

"Thank you," returned the patient, faintly.

Nellie's duties were to administer medicines and to feed the patient when he was hungry. The professional nurse, who was on constant duty during the night, slept within call. It was a somewhat trying ordeal for her, shut up there in a dark, silent room with a wounded man who lay so still that she often bent over him to assure herself that he was alive. But she soon became accustomed to the situation. The invalid was very little trouble. He was patient and never uttered a sound of distress or complaint, and Nellie felt the irksomeness of the confinement grow less as her sympathy with the sufferer increased.

Dr. Dean and a young physician called twice a day to treat the patient's wounds. The eyes were the principal concern—the danger from the other hurts having soon passed—and upon their condition the patient always questioned the doctors anxiously. After a time they were able to assure him that he would eventually see as well as ever, but told him that his eyes would have to be kept bandaged —perhaps for a good many days to come.

After that he required more attention. He was getting better, and, the danger of blindness being past, he wanted to talk and wanted to hear his nurse talk. To gratify him she read aloud a great deal, and he seemed never to tire of hearing her voice. It puzzled him; he felt that he had heard it somewhere before. But he refrained from questioning her on that point, and, as the doctor never chanced to address her by her name in his hearing, he continued to call her "Nurse" and remained in ignorance.

There came a time, however, when the bandages were removed. The room was still kept quite dark, to be lightened very gradually as his eyes grew stronger; and he now occupied himself in gazing at the dim figure of his nurse as she busied herself about the room or read to him by the light of an inclosed lamp.

One morning she arrived to find the blinds wide open and her patient smiling up at her as she at last looked clearly into his face. It must have been a handsome face, she thought, and perhaps would be again, for the scars were rapidly healing. There was a cut high up on the forehead, where a rock had caromed against his skull and where he would carry a mark for many a day; but he had just been shaved and the lower part of his face was smooth and unscarred. He gazed at her with absorbing attention.

"And it is you!" he exclaimed finally. "It was awfully good of you to come to me when I was so helpless."

There was a familiarity about his manner of addressing her which Nellie did not understand.

"Why didn't you tell me?" he went on.

"Tell you what?"

"That you were Nellie Gray."

"Why—I don't understand you. How did you know—

"Do you mean to tell me,"he asked, "that you did not know who you were nursing?"

"I knew your name, of course," answered Nellie. "I also knew that you had given to a mining claim a name which is the same as mine—and I was a good deal vexed, too, when. I first learned that—but I knew nothing else whatever concerning you."

The convalescent looked somewhat crestfallen.

"It was rather an inexcusable thing to do," he said, "but I didn't think you would ever hear of it."

"I would ever hear of it?"

"Yes. You see, I had your card. That's where I got the name for my mine."

"My card! Where did you get it?"

"You gave it to me."

"Why, I never saw you in my life," declared Nellie, "until I saw you lying there!"

"Oh, yes, you did," said he airily. "My face did not look so much like a battlefield then, and it is cleaner now. But have you forgotten when the stage tipped over?"

"Oh!" cried Nellie, her eyes dilating. "And it was you who saved me? How stupid of me not to remember you. And you took my card and tacked it on a discovery stake just to save yourself the trouble of finding a name for your mine," she said reproachfully.

"Well, not exactly," replied her patient. "When I saw you over there I felt sure that there must be luck in a smile like that; and I was right. I had other claims, but I worked on that one because of the name it bore, and it has turned out to be the one with the rich ore chute."

Nellie felt that she must discourage such bland and unbridled flattery. "I am glad," she said, with befitting dignity, "that I have been able to do something here to repay your service to me."

"Yes, you have done pretty well so far," returned the young man complacently.

"I fear I can do but little more," said Nellie, not knowing whether she ought to feel amused or affronted.

"Why, I am not nearly well yet," he rejoined. "You surely will take care of me until I am able to be around."

"You will soon be well," she said.

"Oh, no, I won't. I feel like having a relapse."

Nellie could not suppress a smile. "I can't help it," she returned; "I go back to teaching school soon, and I must have a little time to brush up what scanty learning I possess. Now I want you to eat your breakfast and then go to sleep. You have talked too much."

He was a discerning young man, and he saw the possibility of her leaving him very quickly if he allowed his admiration to have too free expression. So he ate his breakfast, thanked his nurse for it, turned on his pillow, and, whispering to himself that she was the dearest little thing on the footstool of heaven, soon went to sleep.

The beginning of the school term drew near and Nellie felt that she must be relieved from nurse duty. She frankly confessed to herself that she was loath to leave him. He had been behaving admirably, "considering everything," she reflected. But he no longer needed her "professionally," she commented in her mental summing up of the situation. Dr. Dean agreed that she should be relieved, and so she told the patient one evening that the next day must be her last.

"Sorry," he observed with a good deal of cheerfulness.

"He does not care so much," she told herself, and somehow she did not feel quite so light-hearted as usual.

When she arrived the next morning he was dressed and seated in a big rocking chair and was conversing with a man who proved to be his mine superintendent and who soon withdrew. Several letters lay on a table beside the invalid.

"I had to get up to-day," he explained, "as there is some neglected correspondence to attend to. But I find that my right hand is still a little lame, and I am going to ask you to do some writing for me."

"Certainly," said Nellie. She took the writing materials which had already been brought for his use, seated herself near the window with a large book on her knee and awaited instructions.

He took up the bundle of letters and dictated the answers to several of them without pausing. Then he opened the last and sat pondering over it. "Here is an important one," he said. "My eyes are growing weary. Won't you read it to me?"

Nellie brought the letter to her seat and read aloud. It was dated at Colorado Springs, and, following the preliminary greetings and congratulations to the recipient on his reported convalescence, ran as follows:

"I trust that you are now sufficiently recovered to give immediate attention to my proposition, as the conditions of my arrangements with the gentlemen associated with me require it. I have been successful in arranging for the formation of a company, and can offer you $150,000 in cash and one-eighth of the company's capitalization in its stock for a title to your Nellie Gray claim. To insure the fulfillment of this proposition, it will be necessary to have your acceptance in writing by three o'clock on the 20th inst. Truly yours, NORWOOD SMITH."

"What a lot of money!" exclaimed Nellie. "Is the mine really worth so much?"

"That's hard to tell. It is a very promising property, but sometimes gold mines pinch out. What date is this?"

"The nineteenth."

"I must send him an answer, then, to-day."

"Will you sell?" asked Nellie eagerly.

"I must let you decide that," he said.

"Me?"

"Yes. You see, I am getting rather tired of this mining camp existence, and, besides, I have a feeling that I will always be afraid of giant powder hereafter. I couldn't think of giving up my Nellie Gray unless I could get another; but if you would be willing to go back to civilization with me I think I could let it go without much regret."

"Why, Mr. Morrison!" exclaimed Nellie. "I—you astonish me."

"Yes, I know it," he said coolly. "But the question is, Nellie Gray, will you marry me?"

"Certainly not."

He looked up with provoking serenity.

"The idea!" she went on, but in a gradually softening tone. "Why, you have known me such a short time, and------"

"I love you," he said tenderly, as she hesitated, "and I know all about you—as much as I care to know."

"Well, then you have the advantage of me," she returned with an exasperating smile, "for I don't know all about you, you know."

"Why, that's a fact," he said, musingly. "Well," he went on presently, "we must get on with this correspondence. Norwood Smith, Esquire, Colorado Springs, Col.," and waited until Nellie had recovered from her surprise at his sudden change of mood and had transferred his words to a fresh sheet of paper.

"Dear Sir," he continued. "Your offer has been duly received and considered. I have decided not to part with the mine. Thanking you, I remain, truly yours."

"I will sign the letters now if you will bring them to the table," he said, as she finished. "Then you may address the envelopes, if you will be so kind. I want to get the letters off before the stage goes out."

Whatever Nellie thought, she kept it to herself—then. She silently gave him the letters, silently addressed the envelopes, sealed and stamped them, and then stood irresolute before him.

"Shall I take them to the post office?" she asked.

"Oh, no," he answered. "Mr. McIntyre will be back soon and he can take them down. Besides, this is your last day here, you know, and I want to keep you through all of it." He smiled and spoke tenderly, and Nellie's heart smote her—though it felt lighter, for all that.

"I am tired now," he said languidly. "I think I had better lie down."

"Shall I call Mr. Lane?" asked Nellie.

"Oh, no; I can walk all right, you see. But I think you had better put a bandage around my head."

"Does it hurt?" inquired Nellie, solicitously.

"A little." He stretched himself wearily upon a sofa and Nellie wound a band of cloth gently but solidly about his temples.

"Does that feel better?"

"Much better," he said, and thanked her.

"When will Mr. Mclntyre come?" she asked as she lingered over him.

"He said he would be back about eleven o'clock."

Cripple Creek Celebrating.

Cripple Creek Celebrating.

"Don't you think there would be time to write another letter to Mr. Norwood Smith?" she asked softly.

He looked up rapturously. "Nellie Gray!" he cried.

She was on her knees beside him, and—well, the school board had to discover another teacher.