-> My Collection; Magazine is not fully scanned, so no source album to see. But, an online digital version can be found here on the Hathi Trust Library site.

(pages 539-548)

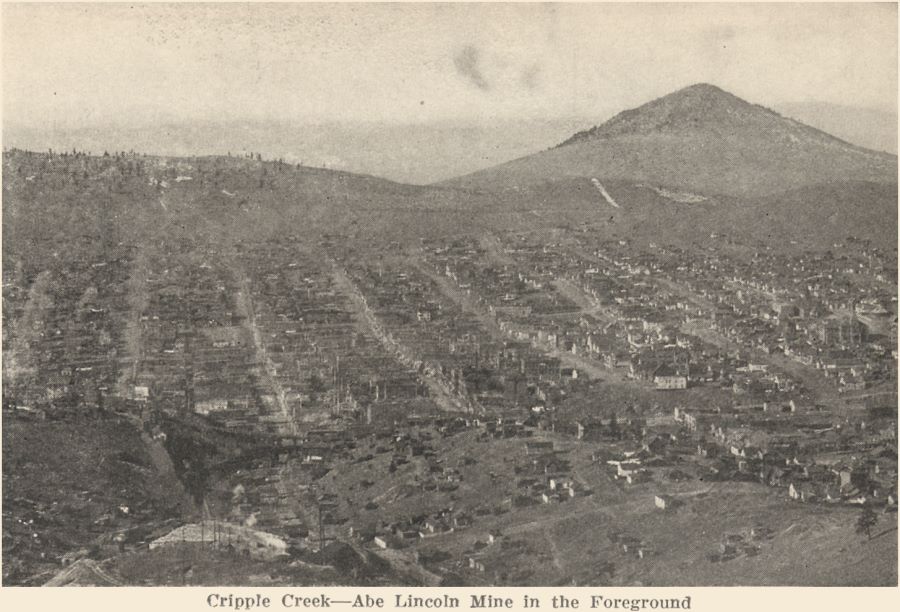

Cripple Crek - Abe Lincoln Mine in the foreground.

Cripple Crek - Abe Lincoln Mine in the foreground.

THE Western Federation of Miners has unionized nearly every metalliferous mine from Canada to Mexico. It has gathered into its ranks all the workingmen employed about the mines, from engineers and blacksmiths to miners and laborers. It has organized a rival body to the American Federation of Labor, through which it controls all the other unions about the camps - the American Labor Union.

The American Federation of Labor was too slow. When the miners wanted to boycott a store or put a newspaper out of business they did not like to have to go to Washington and wait until the "Gompers Machine" got ready to act. The American Labor Union believes in the power of money as well as the power of numbers. It has accumulated a big "defense fund," which is variously estimated at from one to three million dollars.

This new Federation is composed of "practical" men - "militant, alert, tireless, persistent," say their enemies, the Mine Owners, " and criminal," they add. But that is the question. The Governor has answered it in the affirmative. Nothing has yet been decided by the courts.

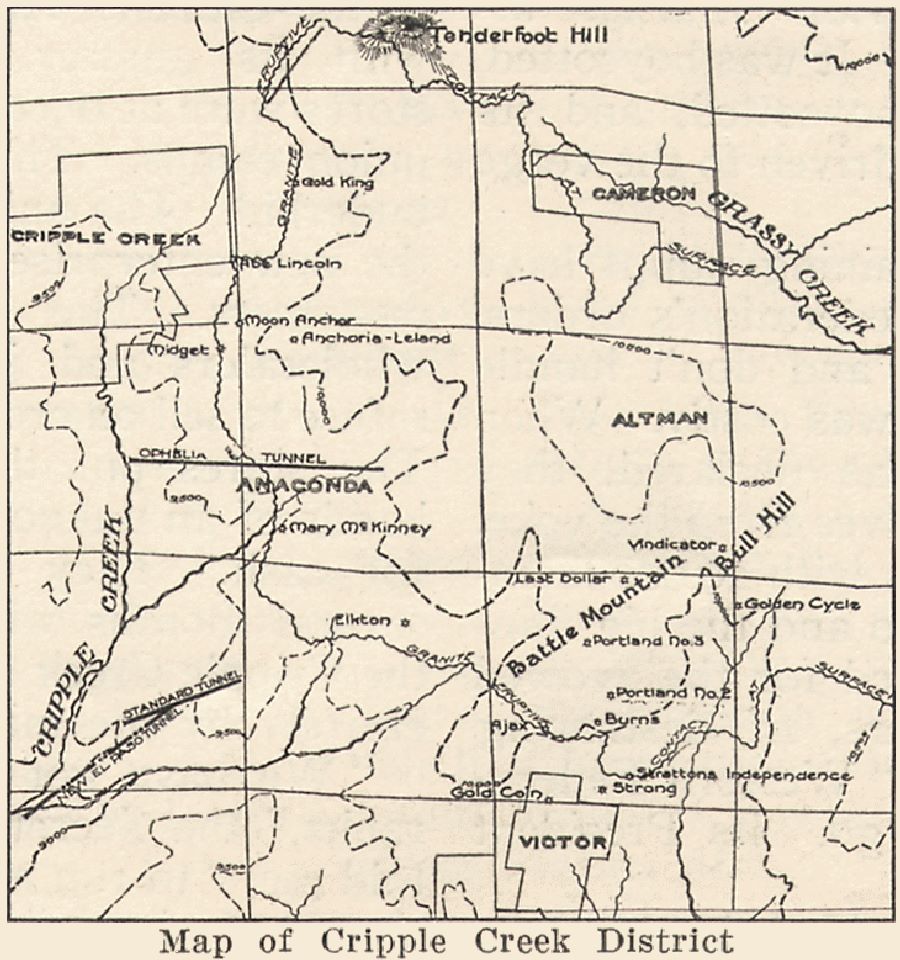

Basic Map of the

Basic Map of theCripple Creek District

The Federation is unquestionably militant. The Denver Post published an article two years ago derogatory to the president of the Telluride union. In three days the paper lost 1,500 subscribers. The writer of the article was discharged. The Telluride Journal attacked the Federation. It was boycotted, its advertisers were boycotted, and its editor and owner was driven to the verge of ruin.

The stores in the mining camps have been subject to the Federation's orders. "It was, handle this and don't handle that," they say. This was costly. When the present strike was declared, they decided to free themselves from the yoke. The Citizens' Alliances, with 29,000 members in Denver, Pueblo and the big mining camps, were created for the avowed purpose, among others, of destroying the Federation. The "Western Federation of Miners must go," its President said.

The Mine Owners joined the Alliance, the bankers and lawyers joined it, and non-union men were cordially invited to become members. A large membership guaranteed patronage for the stores, but to make sure of the loyalty of the merchants they and the financial institutions entered into close contracts to resist all dictation from the unions thenceforth. Next, they refused credit to union men on the assumption that the Mine Owners would succeed in " non-unionizing" the industry.

As usual, the Federation was awake. It had seen for some time the up-growth of the Citizens' Alliance, and was ready with its answer. Union co-operative stores were at once started in each of the union camps. The old stores began to underbid. The union poured money into the new enterprises, and they held their customers.

The Alliance then got the wholesalers and jobbers of Denver to refuse to sell on credit to the union stores. The stores put their purchases in the hands of an unknown person and bought for cash. They had been in business several months when I visited them in the Cripple Creek district. They are run entirely by the miners themselves.

"We have got enough talent in our ranks," the Secretary of the Federation told me, "to run anything from a barber shop to a bank." The Federation has gathered to itself thousands of adventurous prospectors, who differ from many of the Mine Owners only in that they have not been lucky enough to make a "strike." They come from every social class, every occupation and every section. They are of the most diverse character - from the mere adventurer to the enterprising and hardy pioneer. But they have these things in common: They are Americans, they are of an independent temper, and they have seen something of life and the world. They are not much disposed to take anything for granted, and they don't know the meaning of defeat.

The Federation is governed by an Executive Board that sits occasionally in Denver. It is also governed by referendums and conventions, but most of all, it is governed by a triumvirate of executive officers:

Charles H. Moyer, President.

John M. O'Neill, Treasurer.

W. D. Haywood, Secretary.

Haywood plans, O'Neill writes and Moyer executes.

O'Neill edits the Miners' Magazine, that is read weekly in every mining camp of the Rockies. The magazine stands for Socialism first and Unionism afterward - as "an educational force," Mr. O'Neill explained to me. The Federation motto is on the outside cover: "Labor produces all wealth; wealth belongs to the producer thereof." This is also to be found on the back of every union card, "lest we forget," the men explain.

Already the Federation has secured industrial and political control over many of the mining towns. Industrially it has grown strong enough in some cases to exclude non-unionists from the camp. A year or so ago a sign appeared in the mines at Cripple Creek to the effect that the union would not hold itself responsible for scabs that appeared in the mines after that date.

Politically also many of the towns are in the union's hands. Mayors, sheriffs and judges, if not nominated by the unions, owe their election to them. By conviction or interest, their decisions have undoubtedly been friendly. The press in the camps and at Denver was equally well disposed. But when the Federation went against the big corporations at the capital it failed.

A favorite measure for years with the Federation has been an eight-hour law for mines and smelters. Last year they secured, by a majority of 40,000 votes, the adoption of an amendment to the Constitution of Colorado making this measure possible. The political platforms of both parties declared in favor of the proposed law, but through "underground influences," the unions claim, the law was not passed.

The union then decided on a strike against the Legislature. This would accomplish a double purpose. It would serve as a lesson to enemies of the union and it would unionize the mills and smelters. The industrial power of the union also had been threatened in its citadel at Cripple Creek.

Ever since its big victory in 1894, E. A. Coburn, owner of the Ajax and Strong mines, waged war against it. He refused to unionize his mine. But he was compelled to employ union men to complete his force. Among 400 men employed at one time he told me he had 80 unionists. The foreman complained that they were not only restricting their own output, but compelling the non-union men and were forcing them to do the same.

"I could do nothing with them," he said "so one day I had all eighty discharged. The output of the mine was greater next day than it had been when these men were at work." This is one way the union fights. In this case it failed.

But with the mines and smelters in the Federation's hands, it would be possible to force the unionization of every mine that shipped to them in the mountain region. Mr. Coburn was the backbone of hostility to the unions at Cripple Creek. If he could be defeated the biggest mining camp in the United States would be completely in the Federation's power. It was a prize worth contending for, for the output of Cripple Creek is more than $20,000,000, two-thirds of the yearly product of the State of Colorado.

But the Federation reckoned without its host. The smelters were controlled by the American Smelting & Refining Company. The strikes in both Denver and Pueblo failed. The largest mills were at Colorado City, and here the unions had better success.

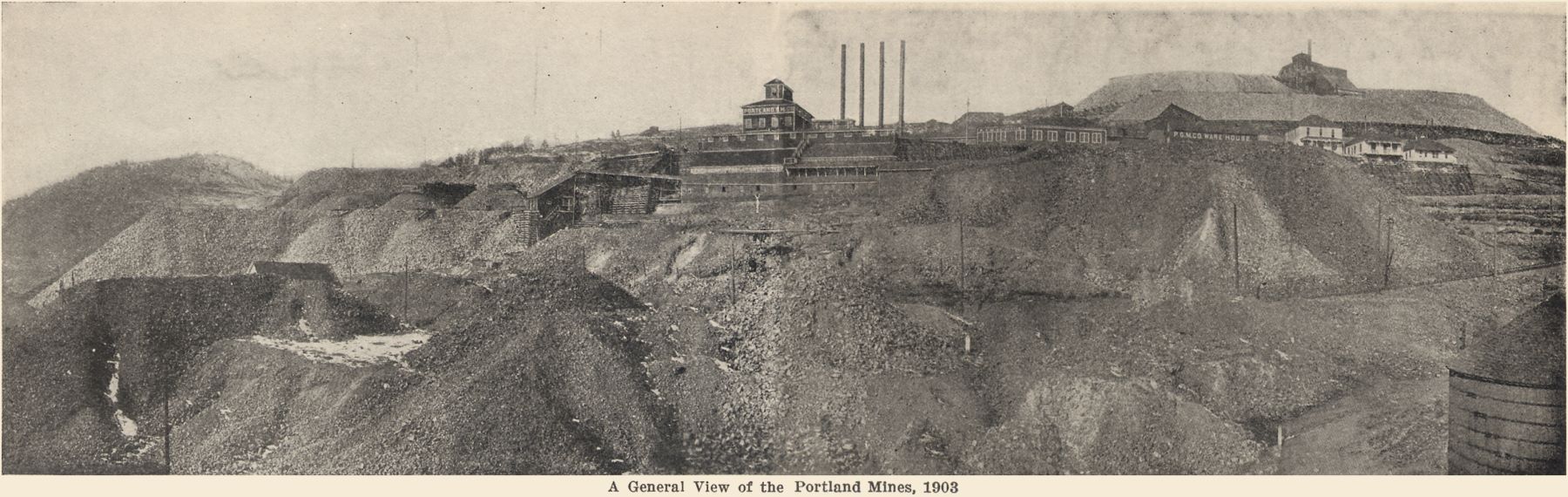

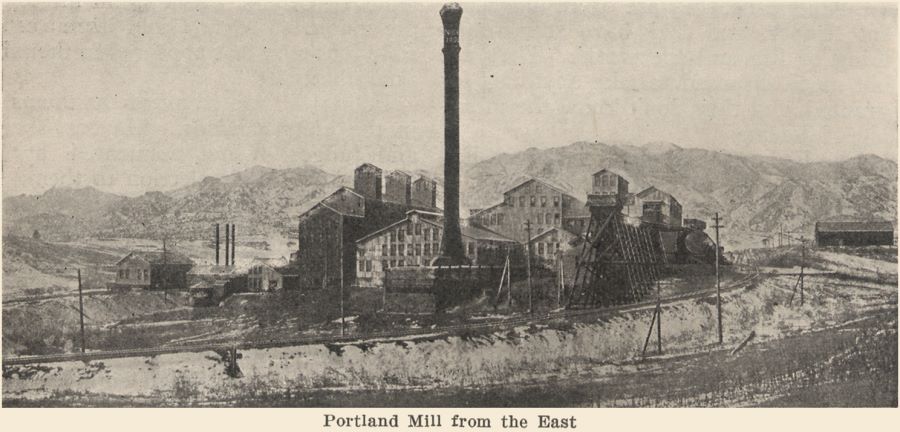

Portland Mill, in Colorado Springs, from the East.

Portland Mill, in Colorado Springs, from the East.

The Governor sent the militia to the scene of action, but after continued protest on the part of the citizens and the officers of El Paso County it was recalled. The owners of the largest three mills, the Standard, the Telluride and the Portland, agreed to the shorter working day and promised not to discriminate against union men. The Portland, all agree, kept its contract.

But the Standard took the union men back, they claim, only at a lower rate than that at which they went out. The miners then called another strike. But the mill had been filled with non-union men, and they were again threatened with failure.

The Federation had staked everything on this fight. But it could do nothing against the "Open Shop." As a last resort it demanded of the mines at Cripple Creek that they cease shipping to the Standard mill.

"The mill men," they said, "belong to the Western Federation of Miners. We don't work with non-union men."

The Mine Owners had been anticipating trouble. Under the presidency of Mr. Coburn they were organized and ready for the fight. They refused to close down at the union's bidding, and thereupon 5,000 union miners in the district threw down their tools. The public called it a sympathetic strike, but the Mine Owners say that there was no discontent among the men. There is no question that the employers were the more dissatisfied.

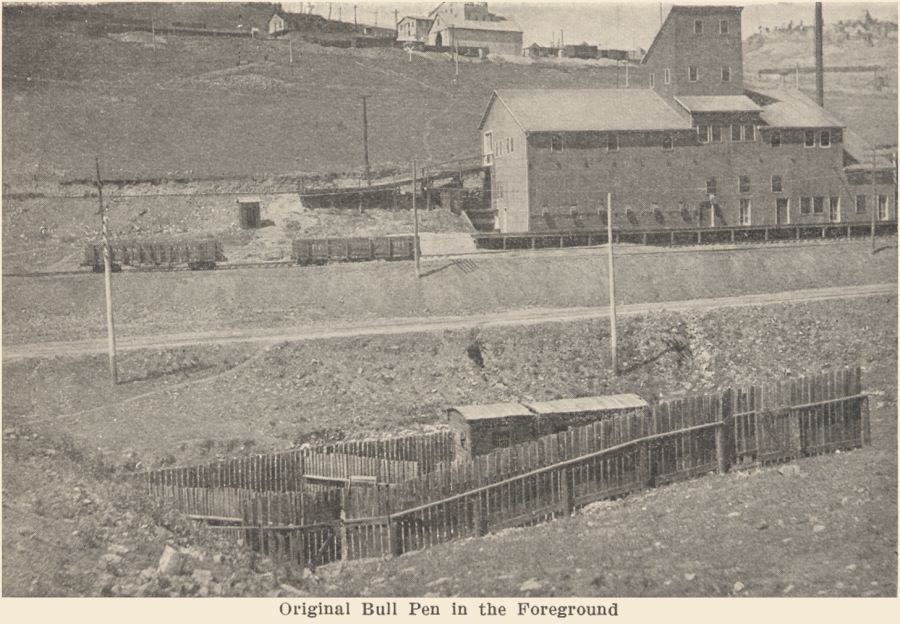

View National Sampler, along Golden Circle, with Eagle Sampler up on hill in background and the Original Bull Ben in the foreground, at Goldfield.

View National Sampler, along Golden Circle, with Eagle Sampler up on hill in background and the Original Bull Ben in the foreground, at Goldfield.

Since 1894 the whole camp has been operated on the basis of the agreement of that year made by Governor Waite. In 1894 the miners won a victory. All the usual methods and paraphernalia of the Rocky Mountain strike were employed. Men were warned to leave town by both sides, bull-pens were operated by the Mine Owners, stockades built by the men, sheriffs were employed by one side and militia by the other, radicals on both sides expressing a private preference for vigilance committees and anonymous threats.

But there was a difference between that strike and the present one. At that time the Mine Owners controlled the county and the Populists controlled the State, while now the miners control the county and the Republicans govern the State. In 1894 the Mine Owners raised $125,000, armed 1,000 deputy sheriffs and were about to move on the stockade where the men were entrenched. At this point the Governor appeared with militia and the county officers were superseded by those of the State.

Governor Waite went first to the union, procured its terms and then proceeded to the Mine Owners. The present agreement was the result. Its terms require laborers to be paid $3 for an eight-hour day and machine men $4 and in some cases more.

Ever since this conflict there has been growing discontent among Mine Owners. At the present moment of industrial depression, when stockholders are becoming more clamorous for conservative policies, directors more suspicious of a showy overproduction in the mines, employers are redoubling their efforts to cheapen and increase production. They are met by the union at every turn. Some have been growing desperate.

Now, the strike had not been on long before the merchants and business men became desperate also. In Telluride 80 per cent, of the business of the town had vanished. When the Citizens' Alliance was formed, they flocked into it almost in a body. "We call the Western Federation of Miners the Western Federation of Murderers," the President of the Citizens' Alliance said to me. The tone of the publications that were circulated in the camp is not dissimilar to that of the Miners' Magazine. One of them says:

"The purpose of Moyer and Haywood is to turn Colorado into a hell-hole for Socialism. ... This dastardly crew is trying to disrupt our entire industrial world.... Colorado is a battle-ground. Every citizen in the State is now on one side or the other. The preliminary skirmishing is over, and both armies are lined up for the supreme test of strength."

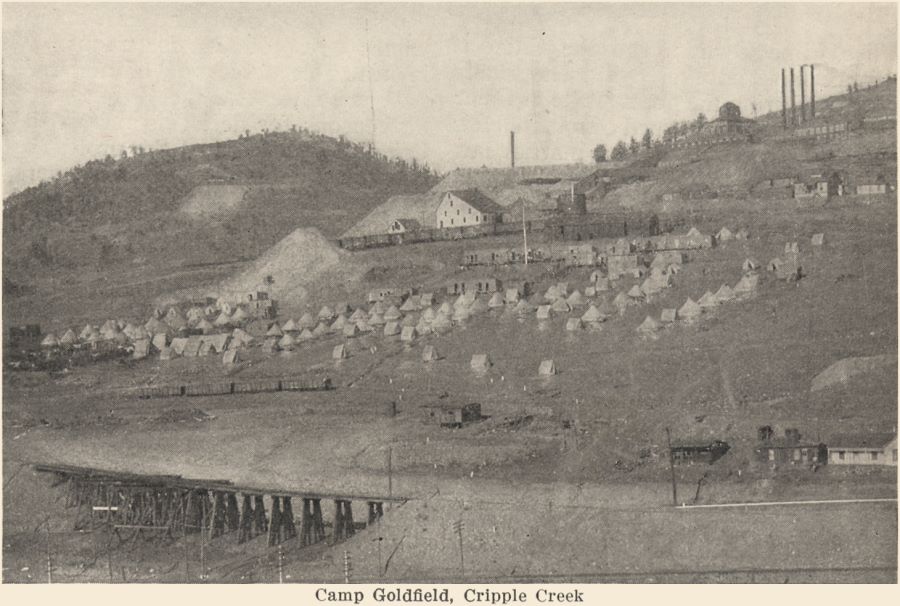

Camp Goldfield, located on Battle Mountain.

Camp Goldfield, located on Battle Mountain.

The Mine Owners and the Citizens' Alliance have uncovered a pretty shady history. During the great strike at Coeur d'Alene, in which a crowd of miners blew up a mine in daylight, and martial law was declared, Governor Steunenberg and the former President of the Federation, Edward Boyce, made a speech, in which he advised every union to have a rifle club," so that in two years we can hear the inspiring music of the martial tread of 25,000 men in labor's ranks." "It is sometimes necessary to blow up a mine and kill a man or two to secure the recognition of the union," was the comment of the Federation's journal the day after the crime.

This was in 1899. The next trouble broke out in Colorado. Two years ago the non-union night shift in the Smuggler Union mine at Telluride was forced

by a body of armed miners to cross the hills at the point of the rifle and leave the county. Several were seriously wounded. It developed that 250 rifles and 50,000 cartridges had been bought from a Denver firm. The order and the draft paying for the supplies were signed by St. John, the president of the union. It was on this occasion that a State Senator sent the Governor this famous dispatch : "No occasion for troops. Mines in peaceable possession of miners."

When I went to the Governor to ask his reasons for declaring martial law in Cripple Creek against the protest of the Sheriff and County Commissioners, he laid emphasis on this past record of the organization. He was especially impressed with an outrage that had occurred about two years before. The Governor had been influenced in declaring martial law rather by the Citizens' Alliance than by the Mine Owners' Association. Himself a banker, he would naturally listen to a plea that had the general support of the banking and business community.

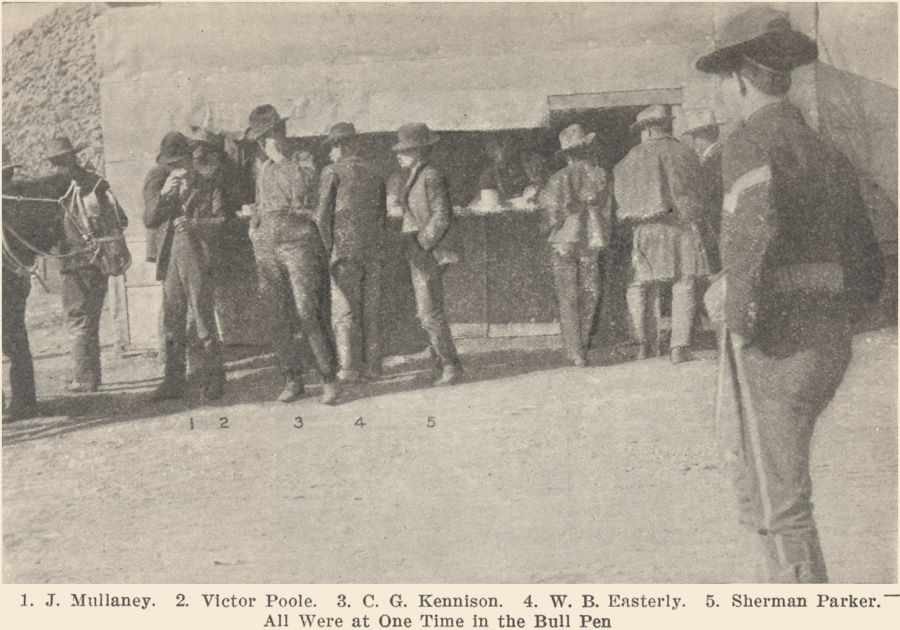

People, 5 is numbered & named, they where all at one time in the Bull Pen.

People, 5 is numbered & named, they where all at one time in the Bull Pen.

But the Citizens' Alliances have been more radical than the Mine Owners. At Pueblo they woke up the president of the Federation and warned him to leave town before morning. A few days later he returned by the special invitation of the Mayor.

At Idaho Springs a mob of Citizens' Alliance members, after the explosion at the Sun and Moon mine, escorted fifteen union men at the point of the rifle outside of the town. It seemed that a lynching was imminent. Every one of these fifteen men has since been exonerated. When new companies were enlisted to serve at the mining camps it was the Citizens' Alliance that furnished the men.

From August, when the militia appeared, to November the strike had no remarkable features. On the 21st of November one of the shafts of the Vindicator mine was blown up and the superintendent and the shift boss lost their lives.

About the same time a rail was removed from the track connecting Cripple Creek with Florence. The first train that came along contained militia returning from a ball. But it was signaled and no harm was done.

The Mine Owners at once attributed both these deeds to the union. But the coroner's jury found no trace of evidence about the mine. There have been no court proceedings which as yet implicated any one in the attempt of the derailing of the train.

The union, which had previously issued orders for the strict preservation of the law, disclaimed any possible connection with either of these events. They pointed to the fact that such accidents as the explosion were common in the mines. On the same day on which this accident occurred a similar one had taken place at Silverton, which, had it occurred a few minutes later, would have killed a number of men. The superintendent of one of the largest mines assured me that these accidents were in no way out of the ordinary.

The Mine Owners and Citizens' Alliance at once applied to the Governor for a declaration of martial law, and it was granted on the 4th of December. Teller County was declared "in a state of insurrection and rebellion." The Citizens' Alliance had convinced the Governor that the State was in danger of revolutionary disturbances. The past record of the union, or, at least, of its members, and its revolutionary utterances had already aroused him to a state of anxiety and fear. His proclamation shows that he, too, was convinced that the Federation of Miners must go.

"There are in Teller County, Colorado," the proclamation states, " one or more organizations controlled by desperate men who are intimidating civil authorities and setting at defiance the Constitution of the State. These authorities appear to be either unable or unwilling to control or prevent the destruction of property or other acts of violence."

The Governor then gives as the immediate cause for the proclamation the fact that certain persons blew up the Vindicator mine, thus denying flatly the evidence of the coroner's jury.

Martial law, not the militia, is the issue in Colorado. Martial law means that property can be taken and persons imprisoned, exiled or even shot without any legal safeguard. A military dictator replaces the administration, the law and the courts. When the militia were put in control they did not delay the exercise of their absolute power. Newspapers were seized and censored, the statements of the Western Federation of Miners were forbidden to be published, houses were searched for arms, saloons were regulated, and in Telluride a curfew law was declared. The offices of the Mayor and Chief of Police were invaded and they were told they must submit themselves to the military. The colonels in command became governors of the military district of Teller and San Miguel counties.

"The militia," said General Chase, " will remain in Cripple Creek until every vestige of unionism is wiped out. Major Naylor explained to me in January the causes 'why we have not yet been able to put an end to the strike.'"

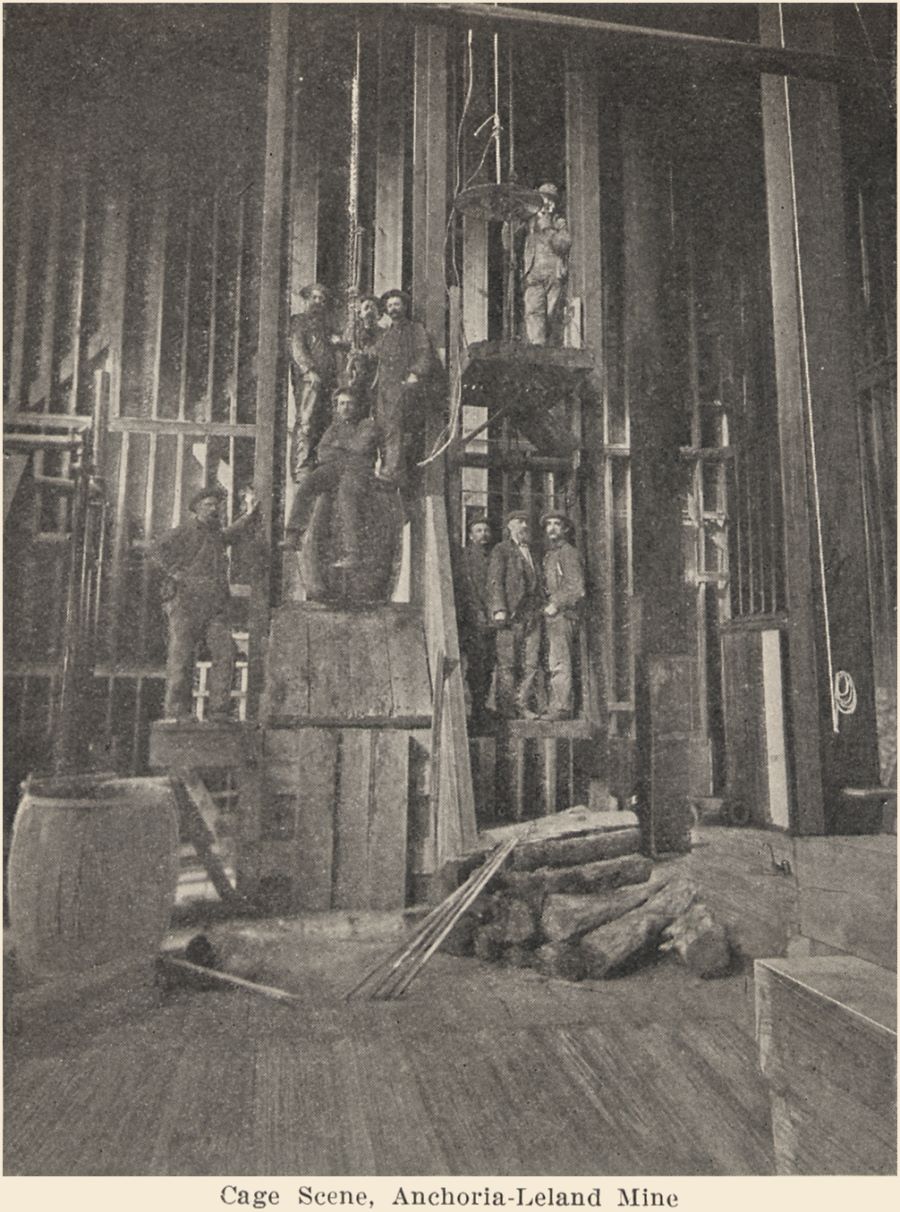

Big Cage Scene at Anchoria-Leland Mine.

Big Cage Scene at Anchoria-Leland Mine.

At no time during the trouble at Cripple Creek have there been mobs or riots, and in no case has there been any murder, with the single instance of a certain woman who was killed in a commonplace dance-hall brawl. Outside unionists were forbidden to enter the county, and nearly all the leaders of the strike were arrested without any special evidence as "dangerous persons " and locked up in the bullpen. Sherman Parker was arrested three times. When his case came up before Judge Hallett of the Federal Court the Judge stated that twice Parker was arrested without any charge being preferred against him and without warrant and due process of law.

At first the men were released by writs of habeas corpus from the Civil Courts. Thereupon the Governor suspended the writ of habeas corpus and the jurisdiction of the Civil Courts was denied. Then came the vagrancy orders and wholesale deportations of union men.

All idle men in the two counties were to be deported. Seventy-three men were exiled from Telluride with no criminal charges against them. They are still refused admission into the county. Included in this number are several who are the owners of comfortable homes and others who own wholly or in part mining claims in the camp. James Teller, the Senator's brother, has undertaken their case against the State.

Senators Teller and Patterson have both denounced the Governor's action. Senator Patterson has gone so far as to demand an investigation by Congress. Former Governor Thomas, in a careful and comprehensive letter, says that there was nothing "bordering on insurrection," that the Constitution does not give the executive the power to declare martial law, that martial law when declared is "qualified " only by the will of the military.

"To declare that, because the law is not enforced, we should have no law at all is to deny the possibility of self-government. The results of political elections are uncertain. We may in time have an executive who will take a lesson from present troubles and better the instruction. His soldiers may gore the other ox."

Governor Peabody has paved the way for a political upheaval. The Socialists all over the country take a grim delight in his action. Their chief organ, with a circulation of several hundred thousand, got out a special issue on the "Class War in Colorado," with large imaginary cuts of outrages and bloodshed.

If the unions are going into politics one of the first fields of conflict will be Colorado. Martial law, tho still enforced in Telluride, has been suspended at Cripple Creek.

The battle is not over. Some of the largest mines are in operation entirely with non-union men. Employers claim to have won the fight, but the Federation says that the battle is drawn and that time is on its side.

"Every scheme of the Mine Owners," they say, " has failed. Intimidation did not, as was expected, stir up the unions to violence. Arrests of leaders failed to discourage the men, and wholesale deportation did not work."

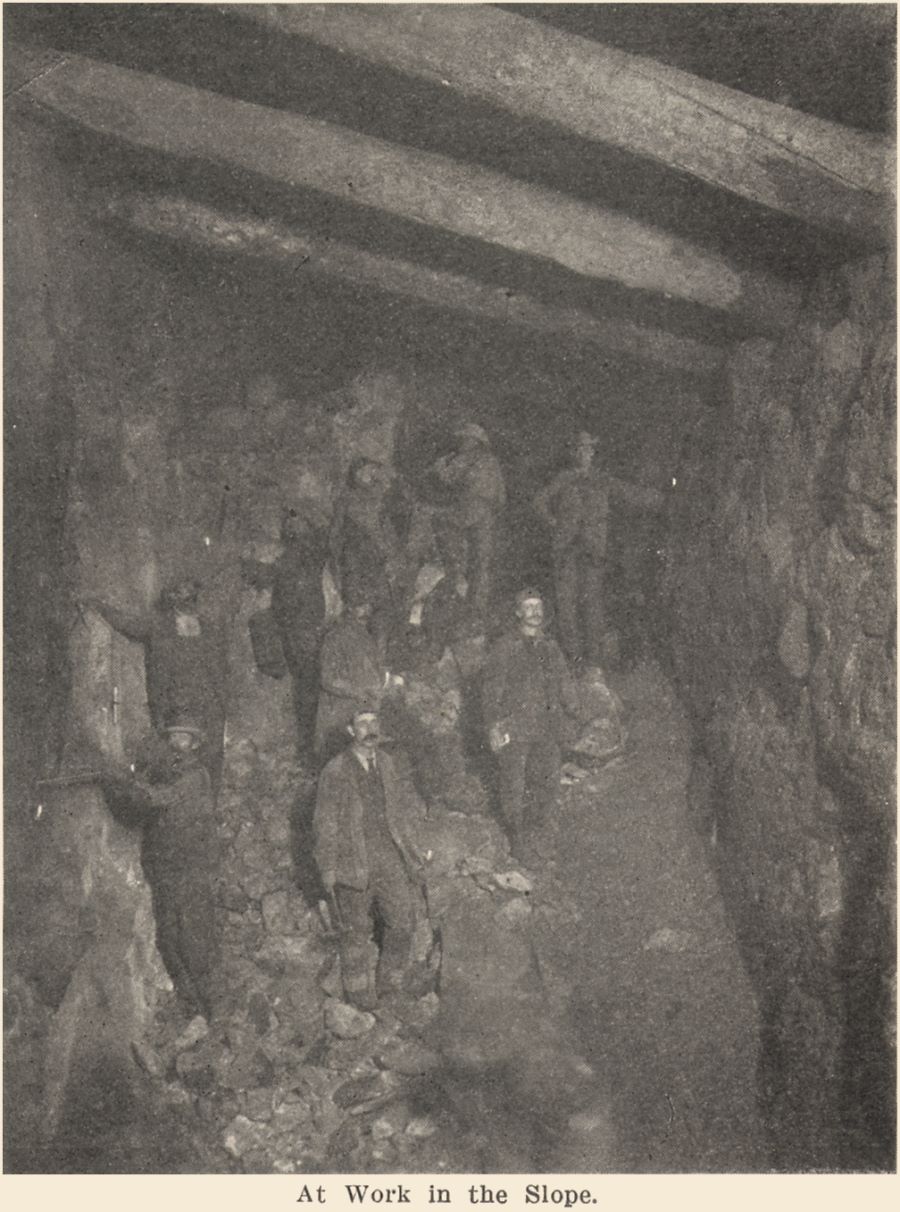

At Work in the Slope.

At Work in the Slope.

There is some evidence in support of the miners' claim. Under the added difficulties of operating with the new men some mines have suspended and others have cut down their force. Instead of 5,000, less than 3,000 men are now employed. Of these nearly 1,000 are unionists. There are perhaps 1,500 unemployed unionists in camp. The mines are running at an increased expense; the output has been reduced. The superintendent of the largest mine in the district, the Portland, showed me evidence that he was producing with union men at a cost of almost $1 a ton less than his neighbor and rival, Stratton's Independence, which now employs only non-unionists.

"We have never had any serious trouble whatever with the unions, "the manager and superintendent assured me," and we find the best workmen are union men." The Portland, with its own union mill at Colorado City, and a controlling interest in the Short-Line, is a thorn in the flesh of the Mine Owners.

Whatever the outcome, the situation is ominous. If the mines are again unionized and Governor Peabody defeated, Unionism in Colorado will be stronger and more aggressive than before. If the strike is lost the spirit of discontent and class hatred it has engendered will be a peril to the industrial future of the State.

—NEW YORK CITY.