-> My Collection, Also on

-> the Internet Archive Site; Link to article.

New Year Edition 1903

(pages 19-24)

I added images from my collection, and procured the coloring of the images, source article had only pic of the man himself

During the year just closed there died, in this state, a man whose name will forever be linked with the history and fortunes of this district, and who will be known and revered long after Cripple Creek shall have become a fading memory.

Winfield Scott Stratton is famed now for his surpassing achievements in the romantic and difficult world of mining, but in the ages to come he will be remembered best for his stupendous philanthropy, conceived, as it was, in love and affection for unfortunate members of his sorrowful, struggling, sinful race.

The world did not understand the quiet, taciturn, but busy man, who gave it the amazing production of his genius. Of necessity, he kept aloof from those whom he loved and for whom he planned during the silent watches of his nights.

By day he denied himself to many of the needy, but by night he worked out, in his active brain, how best he could serve them on a scale so big, so generous and so beneficial that philanthropists the world over were made to marvel at the revelation of love and good will.

This toiling man had but one ambition in life - to help the helpless, irrespective of creed, race, sex or condition. The years before, when the necessities and comforts of life were denied him and the want of them became, at times, so urgent as to cause physical suffering, were but few and it seemed to him but a hazy yesterday.

He knew what it was to be pinched by hunger and to suffer the pain of cold and exposure. He did not forget. How could he?

For twenty long years he dug into the hills and looked up to their summits through a rayless night of failure and hope deferred.

But at length success came, not through blind chance, as many have ignorantly stated, but by dint of marvelous perseverance, almost superhuman toil, study and the exercise of shrewd business judgment. Success came as the natural sequence of a series of effects bearing upon every branch of endeavor in the one direction. He possessed a fine analytical mind and remarkable acquisitive powers.

He applied himself to the difficult field of technical knowledge, of the formation of the barren rocks and their relation to mineral bearing. He took a course in college, and he mastered the blow-pipe.

He engaged to work in a smelter at Breckenridge, and at night, in his cabin in the hills, he stained the pages of pocket manuals of mining with candle grease, studying the intricate details of the business he had set himself the task of mastering.

When he came to Colorado, in 1872, he was a good carpenter, being a natural mechanic and an accomplished draughtsman. But that did not help much in the field of mining. But be used his skill as a carpenter to win bread and meat while he applied the hours not necessary in this in the other branch of endeavor.

His accomplishment in this direction is an impressive, earnest of what a man can do when he sticks everlastingly at a thing.

And then, after failures covering a period of twenty years of suffering and hardship, disappointment and deprivation, success amazing in its scope came to the toiler and student. Almost any other man would have boasted of the achievement and would have thought that it was the test of merit. But Stratton, after all these years of effort and work, remarked to an intimate friend at Colorado Springs, when he was sure of the tremendous success of the Independence mine, that he located and developed:

"This wealth is not mine: it has been given to me to help others, and I will."

This was his shibboleth and his incentive. Every act of this big-hearted, broad-minded man, after wealth came to him, was with this lofty end in view.

Let the many who, since and even before his death, sought, through public print, to malign this wondrous man, calling him a misanthrope and seeking by all sorts of means to place him in a wrong light before the public, because of his silence and retiring disposition, point to a single act in his life, and even in his last will and testament, which is not in entire harmony with the utterance to the Colorado Springs friend.

Let them compare him with other men of similar station who became suddenly rich and see how he contrasted. Great riches did not carry with it the thirst for power, either political or social, that was so common with others.

So far from seeking political preferment, he shunned even the beginnings of it. He had no ambition to become a power along the lines that were such temptation to other men who grew rich in a few years.

He did not want a yacht, nor did he desire a stable of race horses. He did not seek or desire entrance into any coterie where he would have been most welcome.

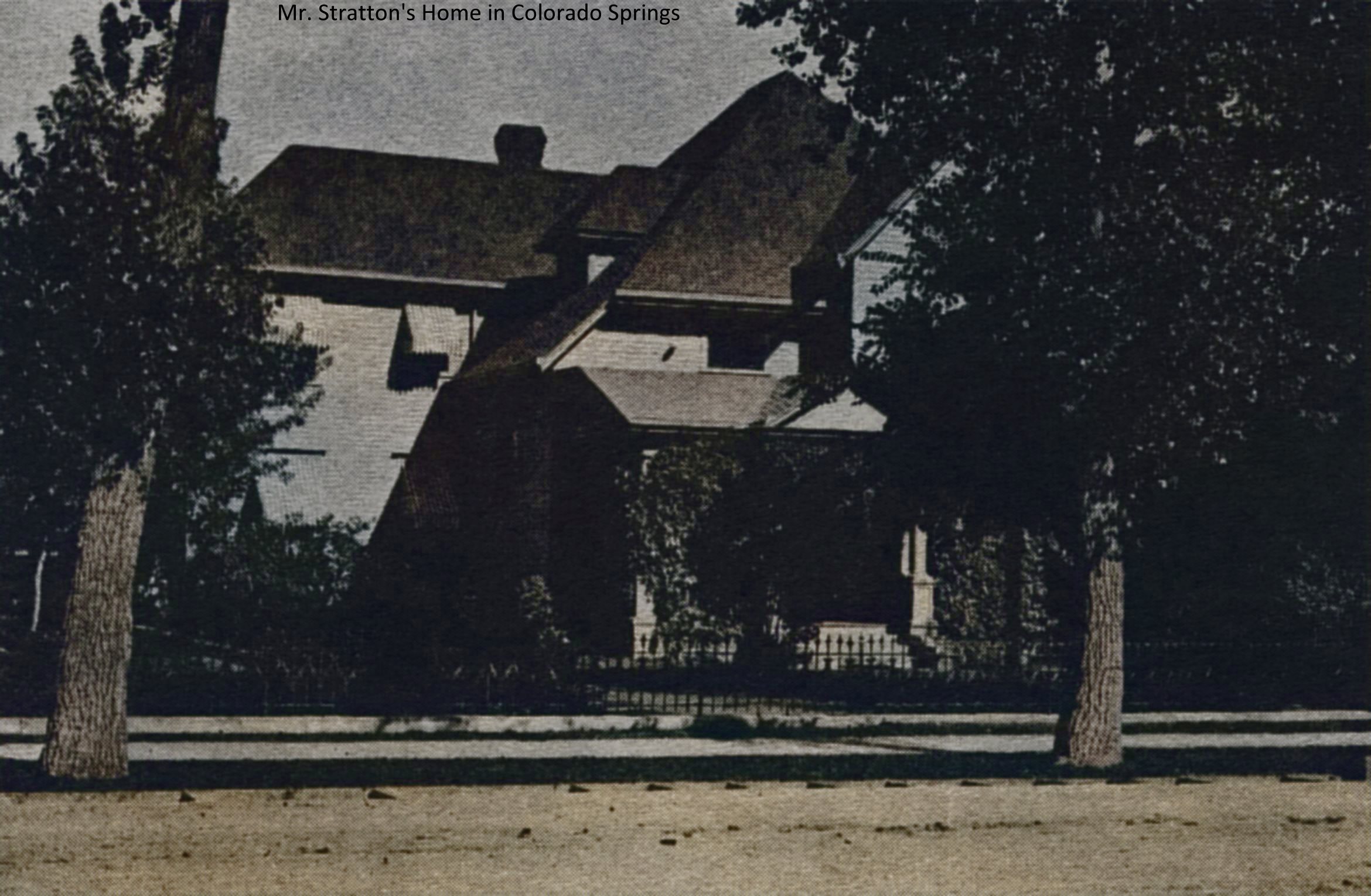

Rather than follow any of these modes of enjoyment for which his keen insight and his great wealth would have entitled and equipped him, he preferred the quiet abode of his modest out elegant home in Colorado Springs. He spent his days at his office in that city planning for the people he wanted to help, and his evenings in his almost humble home, compared with the seats of lavish luxury and finery so common to multi-millionaires.

The home of Mr. Stratton, at 115 North Weber street, Colorado Springs, is perhaps the best index of the man's gentle and retiring nature. The house is modesty itself, the exterior being no better in appearance than the homes of a number of men in the neighborhood who lived on a salary. But on the interior is where the visitor gets the true impression of the strange genius who lived so unostentatiously in it.

He loved music, although he could not perform upon any instrument. But he was an acute critic, and he could not be fooled by technique or the arts thereof. In his home is a magnificent piano, where those of his friends who could perform well used to come and entertain Mr. Stratton with sweet melody.

There were times when he would have none other than the simple tunes that seemed to have gushed from the heart of the composer:

"Like showers from clouds of summer

Or tears from eye-lids start."

These wore the times when his soul longed for rest. The more difficult and complicated music he would call for when his busy brain did not need repose. Then he would enjoy the music that portrayed martial conquest and mighty endeavor.

Some time before his death Mr. Stratton began the work of fitting up one of the largest rooms in the house with exquisite hand paintings. This work, by some of the most celebrated artists in the country, was begun under the critical eye of Mr. Stratton.

There were other pieces of art which he designed in the outline, and the selection of which was made by him. Many of his friends were not aware of this trait in the man. They did not know that a man with such poor early advantages could conceive such purely artistic creations.

Had Mr. Stratton lived this room would have in time become one of the marvels of the West for its superb artistic beauty. The decorations, as far as they went, are marvels of beauty and, although the perfection of the whole would have been necessary to round out the effect upon the eye and the mind, there is enough to indicate that, by nature, the miner who spent so many years digging in the lonely hills was a true artist, and one who loved the combinations that make for unsurpassed beauty in the handiwork of nature's God.

The Stratton home impresses the visitor, on the first entrance, as the place of abode of a cultivated and refined man, and one who has always lived in homes of refinement and has never been warped in his nature by feelings of inferiority. There is in the house just enough of furniture and decoration and bric-a-brac.

There is an entire absence of that overcrowding so prevalent in the homes of men who, having been born in humble circumstances, became suddenly rich and reveal in such arrangement a weakness for display. The furnishing and the decorations throughout are as delicate and as refined as if a lady descended from generations of refined mothers and fathers had made the selections and placed them.

This is in great contrast to the popular idea that Mr. Stratton was a coarse, brusque miner who accidently stumbled upon riches through sheer good luck.

Here in his home are the infallible signs of gentle birth and gentle nature. As those make the least pretensions to respect who have the greatest title to it, so Stratton must be now acknowledged as a man who, though not educated in the colleges or universities, was educated because he thought as he toiled and read and studied in the greater and more impressive school of life and endeavor.

The diploma he received, that of a ripe experience and a true understanding of the great secret of activity in some of the most difficult as well as the broadest fields of trying effort, was the most difficult kind to win.

Others of Mr. Stratton's distinguishing traits were his love for little children and his sympathy for the afflicted, the distressed, the bowed down and the cast off. All of the little tots in the neighborhood knew Mr. Stratton, and as he returned from his office, they would run to greet him and sometimes he would engage in their romps and share in their amusements.

Thus, it was that a poor person with children never went from the tender-hearted millionaire empty-handed.

Mr. Stratton could never resist the appeal of a person who appeared to be suffering. If there were the evidences of affliction, if they were halt, lame or blind, or if they seemed to be in poor health, Mr. Stratton's great heart went out to them in true sympathy.

The thousands of this class of mendicants that he helped will hear testimony to his princely generosity. When one of these got Mr. Stratton's ear, he could not resist his or her appeal.

Often, he was moved to tears by the recital of their woe, and after their departure, when his clerks and secretaries would enter his office, they noticed that his eyes were red with weeping.

Up to a certain time, Mr. Stratton's clerks and secretaries were instructed never to deny him to any one who seemed to them deserving. That is, unless such persons were known to them as impostors, they should be permitted to see the millionaire.

Naturally, such visitations took up a great deal of valuable time from Mr. Stratton, and a corresponding large amount of money, but he gave it freely, and really enjoyed helping personally. The tears of gratitude and "God bless yous" he received were a part of the chiefest pleasures of his life. But in time it came to be known that Mr. Stratton was being imposed upon by undeserving beggars who swarmed his office and his home.

Many impostors had taken advantage of the largeness of the man's heart to tell him lies about imaginary misfortunes and thus got contributions that pauperized them and supported them in lazy idleness. Mendicants would accost Mr. Stratton on the streets and would annoy him summer evenings as he sat out upon his broad veranda.

His condition became almost intolerable and he was forced to begin steps which finally withdrew him personally from the people and which grieved him much.

At heart he wanted to keep in touch with the unfortunates and needy, and help them with his money as well as with a kind word of cheer which he had learned from experience oftentimes helped as much as the financial assistance.

Then a horde of adventurers, blackmailers and swindlers sought to get in their dastardly work. Men whom Mr. Stratton had never seen would have the assurance to make all sorts of pretensions for the purpose of frightening or badgering the millionaire into giving money, solely for the purpose of getting rid of them.

A part of their scheme would be persistence and the making of threats, hoping thereby to extort money. This only resulted in closing the doors upon them, and at length it was necessary to require all coming to run the gamut of shrewd clerks and secretaries before getting to Mr. Stratton.

No matter who came, if the person were not known to the men in front, he or she would have to reveal their business and that in such a straightforward way that it carried conviction.

The result of this was a sore trial to Mr. Stratton. Such seclusion was not in keeping with his sympathetic, democratic spirit, but he recognized that it was absolutely necessary.

Thus, the latter years of his withdrawal, almost absolutely from the public, began, and lasted to his death. Even when he went to other cities it was necessary to keep up a strict incognito. He never registered at the hotels in any city in the country, and when he went about the streets, he used a close carriage. Otherwise it would have been impossible for him to have avoided all sorts of embarrassing scenes created by impostors and beggars.

This brought pain to the man who loved his fellow man and who sorrowed for those in distress. The man who loved the freedom of the hills and the companionship of the stars, to whom nature in all her glory and simplicity and grandeur was a delight and a joy always, was now driven into the solitudes of the city and required to withdraw from the participation in the open life of the communities he loved and for the upbuilding and improvement of which he was devoting his time, talents and riches.

This seclusion and many recurring evidences of the necessity of it preyed upon his mind, and almost embittered his declining years. He wanted to help those who needed it, yet he was placed in a position where he had to do it almost in spite of the very people for whom he had such solicitude.

But that even did not deter him, for it was during these years that he planned his magnificent charity. Denied the pleasure of giving to those who came to ask, he worked out in his brain the details of the wonderful scheme for giving a home to the homeless, where, as the years sapped their strength, they would be enabled to approach their graves in peace and free from that chill penury, the pangs of which he knew so well in his other days of bitter toil.

Riches did not bring happiness to Mr. Stratton, for we have it from his own lips. The only happiness that it brought to him was what it enabled him to do for others.

He builded for suffering and sorrowing sons and daughters of the earth from which he dug his wealth. He planned for those, many of whom, failing to understand him, spoke harshly of him, and he gave them his life in the midst of busy work, the fruition of which was to lighten the burdens of the weary and heavy-laden.

While preparing a sweet rest for the tired, he lay down into eternal sleep.

That riches did not bring him happiness, except that it enabled him to plan to help others, is shown by a remark made to another intimate friend in Colorado Springs, to whom he sometimes unbosomed himself, and loosed the thought and reflection which thronged his mighty heart and brain.

To this man he said:

"If you ever get a chance to sell your mining property for from $50,000 to $100,000, take my advice and do it. I once gave an option on the Independence and Washington mines both for $125,000, and a thousand times I have wished that the holders of it had taken it up, for then 1 would have retired from mining and lived on that money. Too much money is not good for any man; I have too much, and it is not good for me. A hundred thousand dollars is as much as any man should have, if he wants to be happy and free from the bitterness and heart-aches that come with great wealth. And I believe that a hundred thousand dollars is as much money as the man of ordinary intelligence can take care of. Large wealth has been the ruin of many a young man. I would be doing a dear one of mine a positive injury to leave him more money than he is able to take care of."

During the six years prior to the death of Mr. Stratton, the only ray of sunshine in his gloomy life was the thought of his great human beneficence. The planning of this was his recreation, and the adding to his fortune, already almost beyond computation, in order that he might carry out his gigantic dream of philanthropy to its fullest extent; was his chiefest joy.

Those who had become quite intimate with him, though he had few confidants, could detect when this pleasant contemplation crossed his active mind. His dark and solemn countenance would light up with pleasurable anticipation whenever he had a moment for thought on this subject. This was when his heart was mellowed, and when his nature seemed to soften with affection for the whole world.

Mr. Stratton loved to plan, and to work out in his remarkable head the intricate details of a difficult problem. The more difficult, the more he enjoyed working it out to the most minute part. Thus it was that he loved to sit in the twilight, and under the evening lamp, and think about the good that would be derived by those who would be the beneficiaries of his home for the indigent, which was born in his large heart and nurtured by his sympathetic mind.

More than six years ago, while sitting in his home at Colorado Springs, conversing with his favorite sister, Mrs. J. S. Cobb, formerly of San Jose, California, but now living in her brother's home at the Springs, the subject of the home for the poor arose for the first time.

He had expressed to her in outline his earnest desire to establish some sort of institution that would be a blessing to the indigent. He had confided to this thoughtful, sympathetic sister his belief that he had no right to use his great wealth to his own personal enjoyment beyond a certain extent, and certainly not to his own aggrandizement.

She knew, for she had heard it from his own lips, that he wished to apply his fortune in the true interest of the greatest good to the greatest number of suffering mankind. He was not a communicative man, nor a gushing brother, and rarely ever uttered an idle word or a frivolous sentiment. Thus, when he in this wise unbosomed himself to her, and made known to her something of his innermost thoughts, she was interested, and set herself to thinking how she could help him.

Thus, it was that Mrs. Cobb, when for the second time, and in the sanctity of their home, her brother referred to the matter that lay so near his heart, suggested a home for the poor. The interest which the humanitarian showed in the words of his devoted sister proved to her that he had already thought of such a beneficence, and he was pleased that she had thought of it, too.

He wanted to know what her plans were, but, like a true sister, she told him that he could plan far better than she, and that she was quite willing to leave that phase of the matter to him. He said very little else on the subject, and, indeed, talked but little more on any subject that night; but Mrs. Cobb knew her brother well enough to see that the matter had sunk very deeply in his heart.

And there were times after that when she, with her womanly intuition, divined that she could interpret his thoughts, as they wandered over the details of his scheme in behalf of helpless men and women. It became an absorbing thought as the months lapsed into years. The peace that passeth understanding came with the child of his love and affection for his people, the fruits of a union blest, indeed.

At times the silent, thoughtful man's countenance would light up with a joy ineffable, and his great eyes, as blue as the Mediterranean is blue, would give forth a lustre that bespoke an ecstasy of satisfaction.

Those who knew Mr. Stratton best, scout the idea that he was influenced by any one in the making of his will, and the establishing of his great charity.

He rarely ever mentioned the matter to any one. He had learned in the yester-years, when he was struggling to unearth the golden treasure that he believed to be in the ancient hills, to keep his own counsel. He had learned to do without advice, and he had never learned to share either his joys or his sorrows with any one. He had never had really a friend of his bosom, his married life covering only a period of but a few months, and the most of that time he was alone, digging in the hills.

So, this Myron Stratton home was the child of his own brain, and the inspiration of his own heart.

The greatest disappointment of the life of the great humanitarian was his fatal illness, because it precluded the possibility of his inaugurating his philanthropy.

It was his intention to purchase the site and get the home started and established before he died. When he learned that his days were numbered, and quite few at that, the trace of pain that crossed his countenance was not on account of the waste of life, but the loss of the opportunity to see with his own eyes the beginning of a work which he firmly believed would lessen the sum of human misery and add a large share to the total of human joy.

Shortly before his death Mr. Stratton had already made the initiatory beginnings upon the Myron Stratton home, and a few more years of life in his short span would have seen the culmination of the crowning aspiration of a life so pregnant with achievement.

The years following the sale of the Independence mine were by Mr. Stratton devoted to investing the money derived so that the moths of time could not corrupt, nor thieves of carelessness or indifference or greed break through and steal.

Then he wanted to so invest his money that his beloved adopted state could derive all of the benefit possible. There were many ways open to him that left Colorado out of consideration, but he would have none of these.

He put nearly every dollar of his great wealth into this state, and invested it so wisely that the revenue from it would be ample to sustain his charity, and yet leave enough to satisfy, as he thought, those who, because their blood was his blood, felt entitled to consideration. These he fully believed he had done justice by when he made his last will.

He had about finished the great task of investing his money derived from the sale of the independence, within the narrow limitations outlined, and was entering upon the work of establishing the home, when the Grim Reaper cut him down.

The only alternative left for him was to leave behind him directions for carrying out the humanitarian work he had planned and begun. If that work is left undone, it will not be the fault of the benefactor, nor the fault of those whom he regarded as worthy of taking it up where he laid it down.

If after all that has been said of the selfish rich and the grave responsibility resting upon those who hold, as stewards, the wealth that has been given to them for a purpose which they seemed to be unable to discern, it will be a sad commentary upon the institutions of this America of ours if the sublime object for which this one exception to the rich men of the nation gave the best and last blood of his life, is dissipated or defeated.

Here was a man who appreciated the responsibility of holding great riches, and he reached the high mark of the calling of that stewardship.

Will the state do her part? Or will the state make it impossible for an exhibition of man's humanity to man so true and so loyal as intended in the years to make countless thousands rejoice, to live and bless generations yet unborn?

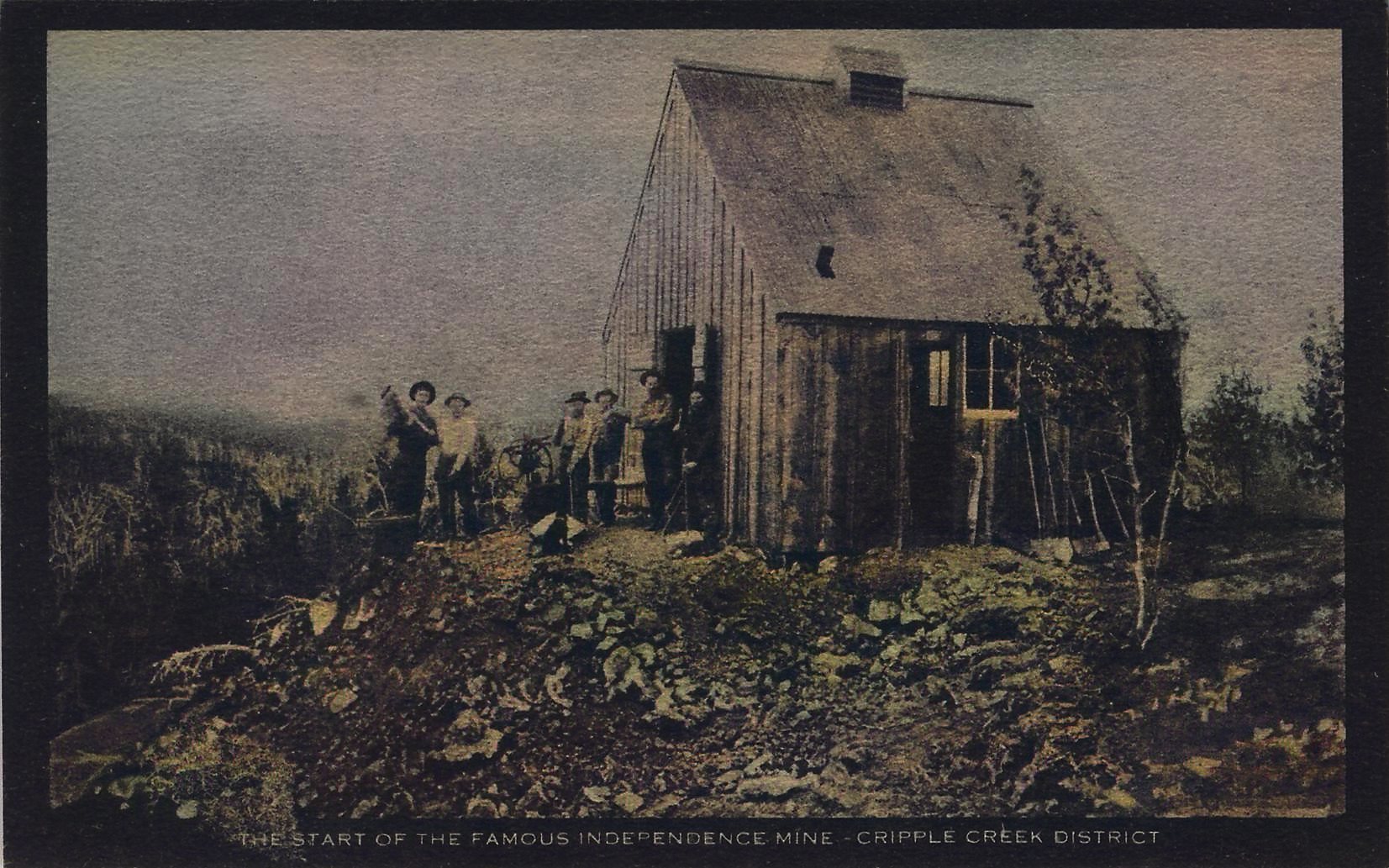

After Mr. Stratton located the Washington and Independence mines, in July, 1892, he returned thither and began development work. Fortunately, perhaps, he began work on the Washington first. He did not find as much mineral as he expected, though rewarded in a measure at a little depth.

He was at that time entirely without money, and in debt besides, having expended all of the savings of the winter before from his carpentering, in grub-staking himself and locating the claims he had discovered.

About this time he sold the Washington for $80,000, and received $10,000 cash. This enabled him to pay his debts, and which he speedily did before he returned to begin work on the Independence. He went to Colorado Springs with his $10,000, and went around through the city and out over the country and settled with everyone who had been good enough to indulge a poor prospector, who for nineteen years had dug into the hills without success.

Many a man would have waited until he got more money out of the other claim, and would have secreted the $10.000 against a "rainy" day.

But that was not Stratton's way. He wanted to show his appreciation for favors shown, and he has often said that it was the happiest moment of his life when he was able to pay out of his earnings as a miner the debts that he owed. After paying everything he owed, he had less than $2,000 left.

This incident is in strange contrast to the many claims for unpaid bills which have been filed against the Stratton estate since the death of the great miner.

Many of those claims are based upon alleged unredeemed promises to pay, yet with minions at his command, we must believe that he died refusing to meet honest obligations simply for a lack of inclination to render unto every man his due.

This is one of the many irreconcilable things that have occurred since Stratton's life work was ended, and finish was written to a record as romantic as fiction, and as marvelous as truth.

It is an interesting fact that when Mr. Stratton first came to Colorado, in the summer of 1872, he was possessed of an ambition to become a lawyer. Before leaving Eddyville, Iowa, where he was for a short time employed as a druggist's clerk, he submitted to an examination by a phrenologist, who prophesied that he had the head to make a great lawyer, and the idea impressed him.

In that plastic state of youth the ambition seized him, and this one thing, more than any other, induced him to come to Colorado, where he hoped to make quickly enough money at mining to study law. His father, Myron Stratton, then a member of the boat-building firm of Logan & Stratton, at Jeffersonville, Indiana, where the son, Winfield Scott, was born, July 22, 1848, being one of twelve children, four boys and eight girls, could not afford to give his son a college education.

But when the youth decided to start out to make his own fortune, his father gave him $500, a liberal sum under the circumstances. This was the only son who grew to man hood, the other three dying as children.

Young Stratton had been apprenticed to a carpenter, and was well equipped for making his way with the capital he had. He worked at his trade at Omaha, Lincoln and Sioux City, where he spent the years that intervened between the time when he left home and 1872, when he came to Colorado Springs.

That summer, soon after his arrival at Colorado Springs, he went out and dug in the hills not far from the city, and thus so early began the years of prospecting and study of the formations of the rocks which finally resulted, in 1891, at Cripple Creek, so successfully.

He would spend the winters working at his trade by day, and at night studying the intricacies of mining. The summer months were each year devoted to prospecting in the hills all around, almost from one end of the range to the other.

Thus, every summer, for nineteen years, he toiled and endured the hardships of the life, persevering with almost superhuman endurance, and working as few men had the capacity and constancy to do.

This fact alone will answer the statements that Mr. Stratton was the recipient of blind chance or sheer luck. From the systematic manner in which he went at the work of prospecting, and the days he put in at study, both of books and the hills, as he found them, there must be the fixed belief that had he applied the same methods to almost any other line of endeavor, he would have succeeded sooner than he did at mining, and almost in as great a volume of result financially.

The fact that a mine as rich as the Independence should belong to one man is no more marvelous than the achievements of the owner. He did not believe in partners. At one time in his life he had a partner who served him badly and betrayed his confidences.

And Mr. Stratton was the kind of a man who never made the same mistake twice. Thus it was that he held on to the Independence as sole owner, and developed and organized the work along that line and on that principle.

The romantic story of the building of Mr. Stratton's fortune has been often told and will not be repeated now. The object of this publication was to deal more especially with the remarkable character of the man, and to turn the light of publicity, to some extent, upon the dark places of his Titanic mind and heart.

This feature of his life is interesting, because so little of him was really known, and much that has been printed is not true.

Mr. Stratton's first investment in a mining venture was in the winter of 1873-1874, when he put $3,000, all of the money he had, in the Yretaba mine, near Silverton, purchasing a fifth interest. This proved a flat failure, and Mr. Stratton lost every cent of his money earned at carpentering at the Springs; but he was not discouraged.

Indeed, it seemed impossible to discourage such a man, so persistent was he.

The next summer found him again out in the hills with his pick. The formation of the mountain, the relations of ore-bearing to barren rock, he studied with interest and care. Besides, he was a close student of books.

He mastered the blow-pipe, and took a regular course in assaying in Colorado College. To further equip himself for his struggle with nature, he secured employment in the Nashold mill, at Breckenridge, where he got a good idea of the technical knowledge which was to serve him so well at Cripple Creek in the years before him.

So it will be seen that Mr. Stratton did not leave undone anything that would make him an intelligent prospector.

In the early spring of 1891 he was found over on Cheyenne mountain, where he prospected without success, as he had done for eighteen years; but, undismayed, he pressed on.

He pulled up in May, 1891, with his burros, at a point in the mountains which is now so well known as Cripple Creek. He had the false alarm of Pisgah mountain to dishearten him here, and, besides, the mining engineers had looked over the country and had wisely shaken their heads, saying there was no mineral there.

It was impossible, because it was contrary to all theory and precedent. But Mr. Stratton had learned enough to know that theories in mining were made by discoveries of gold in the hills.

He believed, in spite of all that was said, that the geological formation and structure of the rocks, the dyke formation, and all the indications pointed to the fact that here was a great mining region, and he threw his fortune with Cripple Creek.

Stratton was one of the first three experienced miners to visit Cripple Creek, all of whom were at his death millionaires and men prominent in their state.

Mr. Stratton first stuck his pick in the ground near the head of Wilson creek and located four claims. He found some rich ore, but the relations of the veins and dykes to the contact between the granite and eruptive rocks did not impress him as a formation that would prove to be of reliable or permanent value, and he abandoned his claims.

Some of them have since been developed into great mines.

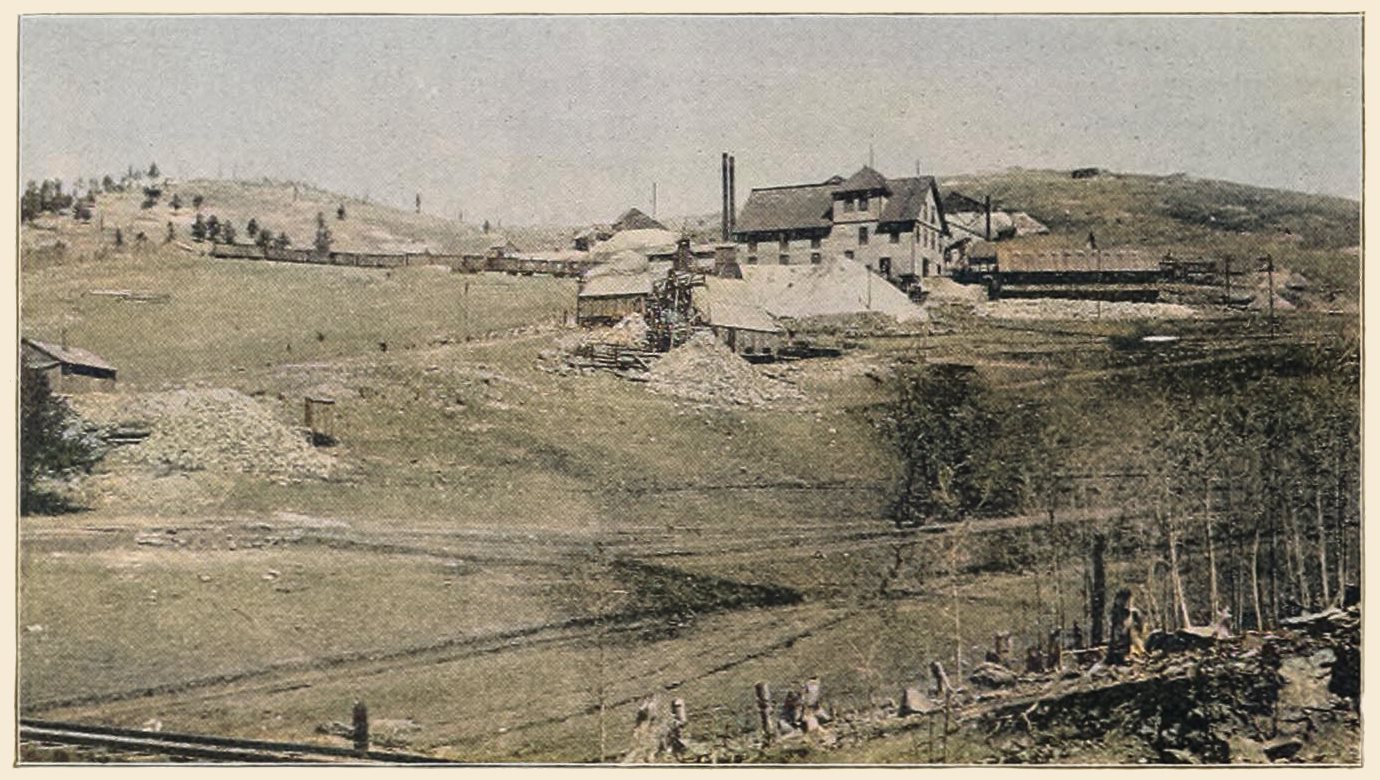

The following June Mr. Stratton prospected the slope of Battle mountain, then not considered as being mineral bearing. Here, at the base of the mountain, he first saw the big Independence dyke, an immense rib of rock that had been forced up through the surrounding and older formations. The trend of this dyke was directly at right angles with the line of contact between the two characteristic rocks. This fact, and the formation of the region, fitted in with Mr. Stratton's theory.

He took some small samples of rock and tested them, after returning to his home at Colorado Springs. He found some gold, and, as he gave more thought to the dyke, the more he became impressed with the idea it was valuable, and was, in fact, what he had sought for nineteen years.

On July 4th he returned to Battle mountain and located two mining claims on the big dyke. In honor of the day he named one the Independence and the other Washington. Then followed the hardest and the most trying work of all the years he had devoted to mining. There were many obstacles in the development of the mines.

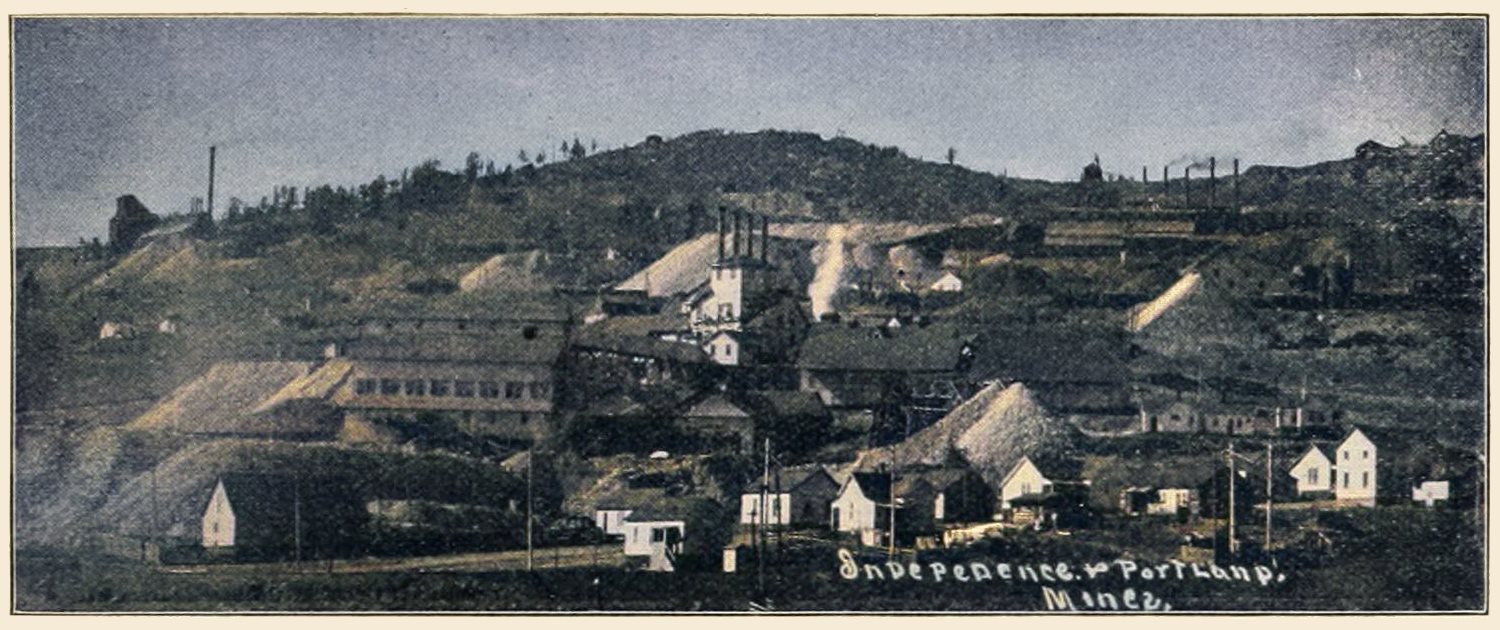

This part of Mr. Stratton's achievement is considered by mining men of experience the most creditable and truly remarkable of it all. The sale of the Washington enabled him to go ahead, keep out of entangling alliances.

He aided in the organization of the Portland and, by a consolidation which he effected, added to the value of the property $4,000,000. This was regarded as the shrewdest piece of mining financiering of the time.

Mr. Stratton had had no experience in mine development but the work on the Independence, all of which was done under his personal direction and the beginnings with his own hand, was considered by all mining engineers as a model of its kind, which old mining men copied and are still copying.

An English mining engineer who had served in South Africa pronounced it, after inspection, the finest piece of development work he had ever seen, saying:

"The Independence, with its miles of levels and thousands of feet of development work, is remarkable for its skillful direction and, on account of the excellent system followed, is as easily reviewed and inspected as the ordinary prospect hole."

Mr. Stratton worked and builded better than he ever dreamed of in his earlier days. To a friend he remarked that he had no desire or thought of opening up such a stupendous mining property as the Independence.

It was his ambition, he said, to find a good mine and, by the use of an old Mexican arastra, grind out about $10 per day. He would have been thoroughly satisfied, he said, to have accomplished this.

As an illustration of Mr. Stratton's reliance upon a settled idea of his own as to where gold could be found, a friend relates that, when he first returned from prospecting on Battle mountain with his samples of rock, he found nothing in them that would impress a less determined and informed miner.

He brought back with him 180 different samples of ore which, on the evening of July 3, 1891, he had assayed. The best assay yielded only $1.80.

Yet, he went to bed that night determined to fight it out on that line.

His couch was tossed, and it was late before he got to sleep, but tired nature nursed the tender thought to reason, and on reason built resolve. The next morning, he saddled his horse and went back and located the great Independence on that slender showing. This he did in the face of the fact that he was worse than bankrupt, for he was in debt, with no assets but willing hands and an honest heart.

Mr. Stratton used to tell an amusing incident of his first visit to where Cripple Creek is now. He loaded up three burros with tools, provisions and supplies for the summer's work at prospecting. When he was about ready to start the agents of the Humane Society got after him for overloading the beasts. He was detained some time, but finally eluded their vigilance.

Those burros earned several large contributions for the society, which it received in later years. This showed that Mr. Stratton had at least a forgiving, if not a forgetting, spirit.

Mr. Stratton was a nervous, high-tempered, impulsive and sensitive man. He was quick to get angry, and as soon over it, and ever ready to make the amende honorable. He was reserved and retiring to a remarkable degree, and generous to a fault. His modesty was perhaps his most distinguishing trait. He could never tolerate show or display.

When he aided needy persons, he always requested that they should not tell it to anyone. If they violated this injunction, they could never again receive any benefit from him. Mr. Stratton gave away several fortunes during the ten years that he was accounted a rich man. His benefactions will never be known in their entirety.

His gifts to public institutions were numerous and were always made on the same conditions, that he hedged about the rest—secrecy.

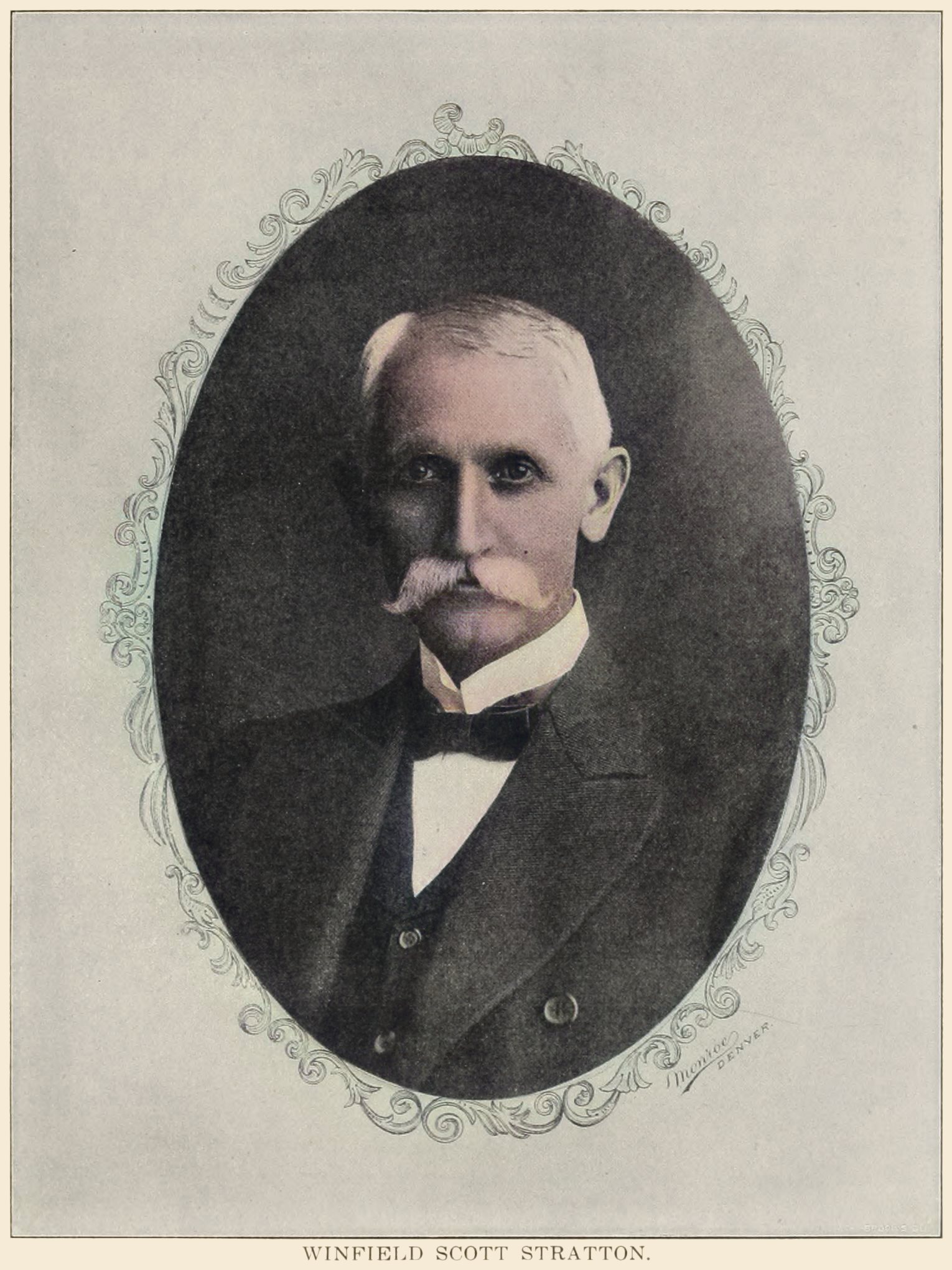

He was a quiet, taciturn, self-contained man of the simplest manners. He vied with Diogones in the ability to reduce his wants as the occasion of health and fortune required. He was of medium size, in stature, rather slender, sinewy and of a nervous temperament. His hair and mustache turned gray prematurely, and with his deep blue eyes, pale patrician features, and snowy hair, made a picture of refined elegance rarely seen in a man of the world, and one who had been buffeted about by fortune as he was.

His manner was plain, straight-forward and unaffected. He was the one man whom success and riches could not alter, either in modes of life or disposition. It was said truly of him that he was a man absolutely devoid of vanity, perhaps the rarest trait known to humankind.

In his days of great prosperity, he never forgot any of the friends of his toiling, suffering days and remembered them substantially. And, whenever he had a quiet evening with friends at home, the board separated him from many a man who was unused to such distinguished attention.

Winfield Scott Stratton is no more, and we shall not see his likes again in many a generation to come. The world that he loved did not observe the ancient injunction of the wise old Roman, "Nil nisi de mortuis bonum est," and some have gone further and said things about him that were not only not good but not true.

But those who know him best honor his memory most, and that is the truest test. It is their verdict that all of the world can point to him and say, "he was a man."

Let time and its mutations work as they will, they can not touch the harvest of a suffering people's love, garnered beyond them.

_battle-mnt,washington-mine_strght-crpd-colored-scld1980.jpg)