- 1903 article

-> My Collection, Also found at the Internet Archive Site. Link to first page of article.

New Year Edition 1903

(page 34-35)

I added images from my collection (framed in black), and procured the coloring of the images, source article had one pic used.

|

A WOMAN'S IMPRESSIONS OF A SHORT LINE TRIP |  |

"All Aboard!" - that old familiar call, that always sets one's wits to hurrying - and we were off for our first trip over the Short Line. The day was bright as gold - one of those incomparable early June days that can be matched nowhere outside of Colorado.

There was the usual hurry and scurry, for there are always the belated ones on any train, and presently the engine began breathing and puffing for the mighty spurt she was about to make around Pike's peak to the gold region.

My place was one of much envy, for it had fallen to my lot to ride in the cab beside the engineer. The engine was a beauty of burnished brass and steel, and she fairly exhilarated with life and energy. In a few minutes we were out of town, away from the belching mills and smelters, throwing miles behind us in the struggle with space.

The deep, guttural puffs of the engine soon subsided to a smooth, even breathing like the purring of a well-fed tigress. We were gliding over the tracks without a jostle of friction. It was like being on the back of some huge monster that crept, with velvety tread, up the mountains, as if climbing were the merest fun.

The way in which the engine took the steep grades and the grace with which we rounded the curves were a revelation. The one effort seemed to be to run ahead far enough to just keep from butting into the rocks that loomed before us, and at the same time to avoid running straight down the gorges that yawned below us.

A few miles made no impression on the peaks about us - they were there, exactly as far off, and of the same size. More miles still made no difference. Soon we were making acquaintance among the clouds, and the peaks looked frostily on, and, as we climbed, the peaks also climbed - there was no getting away from them now.

Up, way up, we could see the snow lying in great white patches on the shaded sides of the peaks; surely here were all seasons in a day, for winter peeped surlily out of the shadows and relented not a whit at the advances that summer was graciously making.

Unlike other mountain roads that creep along the valleys and gorges of the natural water-ways that nature has dug between the mountains, the Short Line hugs close to the crests of the mountains, and it is here that its distinctive characteristic lies.

You are away up, thousands of feet above the surrounding country, and the plains east and south of you stretch on in hazy indefiniteness, miles and miles of drab-colored monotony. Sometimes the plains country takes the appearance of a vast sea, and then again at other times, when the atmosphere is white and tremulous with quivering heat, it is no trick of the imagination to liken it to a desert, with Colorado Springs, Pueblo and the smaller towns that can be seen from the highest points as small oases of verdure.

The near-by scenery compares with nothing that one can remember having seen before. It is even unlike other mountain scenery. Usually one has to stare blankly upward at the mountains, and a few hundred feet tower mightily above man's stature.

But here we are on a parallel with the heights - as one might say - and we are darting from peak to peak, and all below us are dark, forbidding looking gorges and canons. Here everything is vast and overpowering.

The mountains are all about one - great monuments of silence that rest on the very foundations of the earth. Involuntarily a shade of sadness passes over one as we are reminded of our fleeting insignificance.

"What is this all about?" the mountains seem to say, scornfully; here to-day and to-morrow a memory with last summer's rose leaves, and yet man conquered the rude hills, and hewed a pathway across them that will endure as long as the hills themselves.

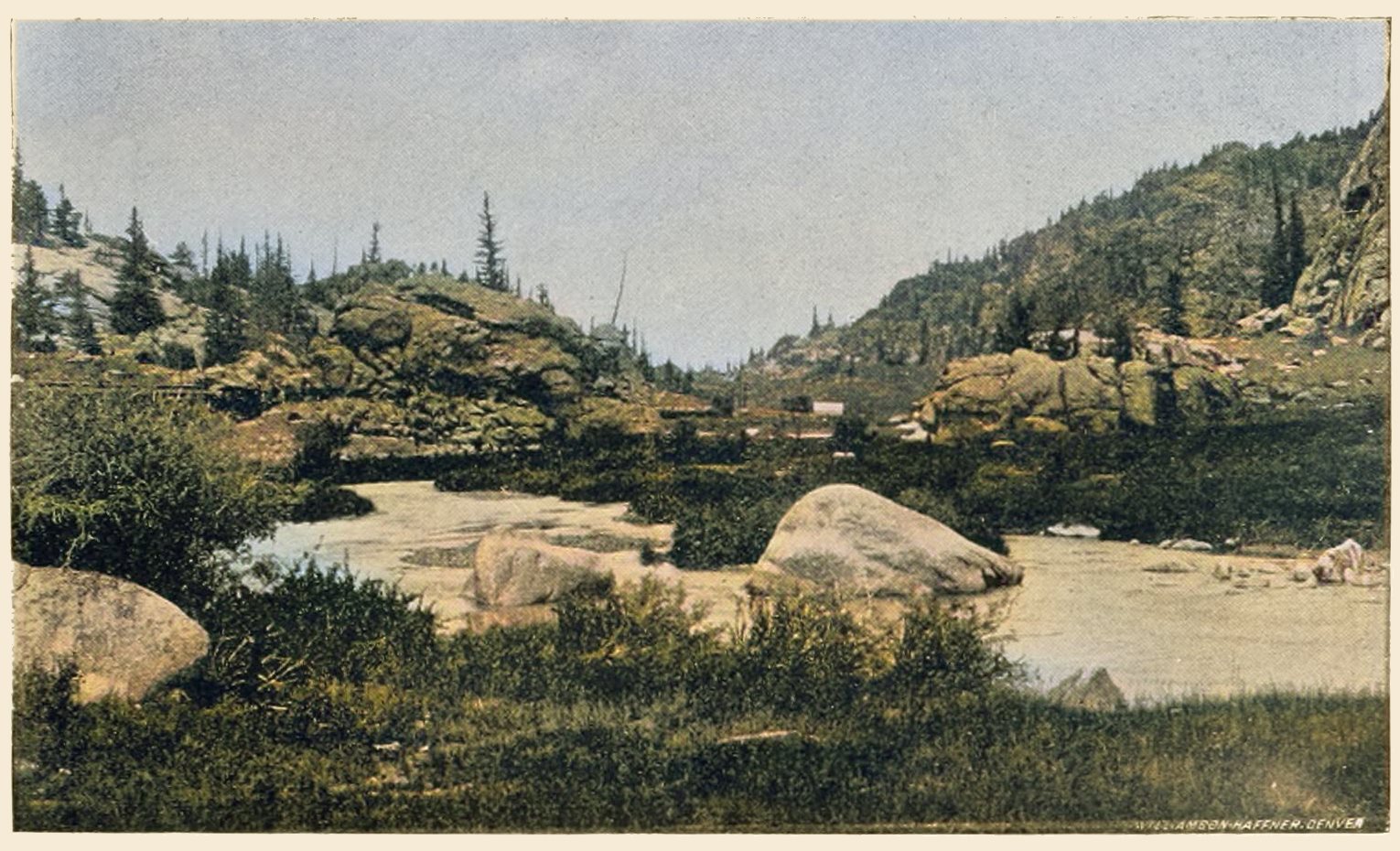

At one of the most beautiful places of the trip the train stopped for several minutes. Some one has aptly called the place Point Sublime. Many of the passengers alighted to get a better view. Sublime it surely was - a sheer, unbroken declivity of pinkish red granite, fully a half a mile in height, the lower part covered with the tender green of the aspen, and higher up came the darker verdure of the pines and cedars, and here and there was a flowering cherry or a haw bush, and exquisitely blended with all was the russet browns and deep reds of the granite crags that jutted above the verdure.

Was there ever a picture painted half so beautiful? - and yet all that had eyes could possess it. It was ours for the mere looking. The view from here makes one's heart swell with the joy of merely living and having eyes with which to see the wondrous beauties of the world that God has created for us.

All about you are the spires and steeples of a vast city of cathedrals, and at a wide break between two peaks one can see the plains that stretch beyond, miles and miles of the short grass country flattened out to meet the horizon, and the imagination stops to wonder what lies beyond.

On the north side of the rocks the snows on the shaded sides made a picture of extreme contrast to the appearance of the sunny slopes, where anemones and gentians bloomed in rare perfection. The forgetmenots are also found in this altitude.

Sometimes the flowers grow apparently right out of the rocks. Seeds lodge in granite crannies, and are housed and warmed there to bloom, when other breezes come along to carry the seed still farther. One of us had picked a bunch of flowers, and among them was a particularly fine columbine, and just as we were about to board the train along came an impudent bee, which swooped down on the flower with the manner of a cavalier, and after taking his tribute off he buzzed, leaving us reflecting - but those reflections are another story.

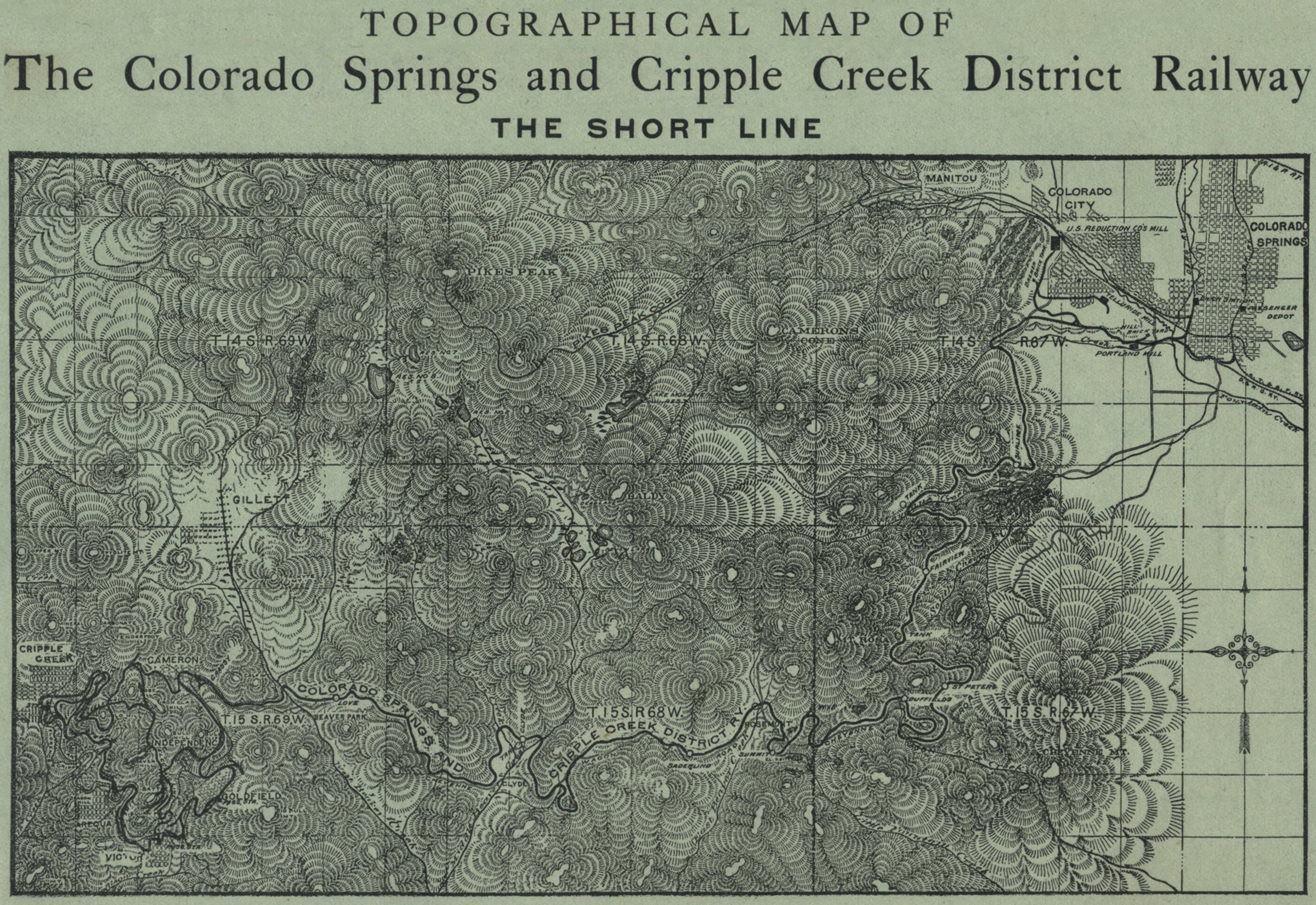

A map of the Short Line must look very like a spiral twisted into the shape of some grotesque Chinese character, for there is scarcely a half mile of straight track along the entire route. Certainly the man who planned possessed a poet's imagination and the daring of an adventurer.

The way circles, reverses and curves in a manner that is an astonishing feat of engineering.

Just as we were passing through one of the wildest portions of the mountains suddenly there was a great commotion throughout the train. For a moment we thought of outlaws and train robbers, and then - well, there wasn't time for another thought when we saw a deer - certainly one of the most graceful animals in creation - standing momentarily still, looking at the train in startled amazement, then off it dashed, its antlers hewing a path through the green thicket.

We saw it as in a flash, then we didn't; but the trainmen declare that during the unleafly season of the year it is no uncommon sight to see deer along the routes, and they may be frequently seen far down near the streams that wedge their way between the mountains. But for us the sight was decidedly a western one, and we appreciated it.

Soon we had reached the highest point of the route, some 10,000 feet, and presently the engine ceased puffing and went along silently as if tired out - but the fact was, the grade being decidedly a downward one, the momentum of the train almost kept it going for the rest of the trip.

The mountains moulded themselves upon another and sort of spread out. They are less awesome, and there is less of contrast, or perhaps the mind has become so used to great heights and fearful depths that only the most superlative exaggerations could still make an impression.

We were now on the other side of the range, and Cripple Creek is only a matter of a few miles distant. Away off, possibly - but it is better to be prudent and spare the ridicule of a hazarded guess - away off lay a rim of evenly serrated mountains - the Sangre de Cristo range - a range of mountains that look as if they might be the end of the earth.

Certainly some such thought must have been in the minds of the first pioneers, for here was a gigantic stockade which nature had erected, and it seems as if there was no getting beyond them - they stretch north and south as far as the eye can see.

The north side of each peak is a sheet of snowy whiteness, and the south side is blue of various tints, and so they alternate for two or three hundred miles. It is a sight alone worth coming to see.

And here, at last, down below in a great bowl-shaped valley, lies Cripple Creek, a good sized checkerboard - that is what the town looks like to us who are several hundred feet above it. But Cripple Creek is another story, and a decidedly unique one at that.

Now, what would you not give to have your enthusiasm whetted and exhilarated with all the keen delights of vivid first impressions?

The trip over the Short Line, at any time of the year, is a bracer for your enthusiasm like nothing else, and, no matter what may be the seasons down below, there are views along that route that can be matched nowhere else.