-> My Collection; Magazine is not fully scanned, so no source album to see.

(pages 256-260)

[colored views not part of article]

Among the Clouds

Among the Clouds

"OVER canyon and crag to the land of the clouds." It sounded attractive. The day was hot and murky, the city noisy and dirty and dull, and life one long "demnition grind."

I looked at my friend. A gleam of interest was in her eye.

"Let's go!"

"To the clouds? how, in a balloon? if so, dearly as I love you, I shall have to decline, I am too much of a coward."

"But how if we go by rail ?"

"Then I am with you."

"Come, then, let us waste no time, for 'vacations are short and time is fleeting'."

In less time than it would have taken a woman of the old school to pack a bag and do up her back hair, our plans were laid, our tickets bought, and we were speeding away to "cloudland."

At the pretty, picturesque little city of Colorado Spring, which lies nestling at the very foot of Pike's Peak, we boarded a train on the Short Line. Then the really interesting part of our journey began.

Starting from a level of 6,000 feet we climbed straight up to something over 10,000 as smoothly and apparently as easily as if running over prairie roads. For a little way, upon the green level of the prairies, we caught glimpses of what was before us, as the vast pile of mountains, range upon range, and peak above peak, rose up against the wonderful, metallic blue of the sky, with Pike's Peak, white-capped and solemn, standing like a guardian at the portals.

"You don't mean to tell me we are going up there in—in a train?" I gasped.

"Sure," answered the conductor, with a cheerful grin; "to the very tops of some of them, and over the tops of the rest."

We exchanged glances, and I think both our thoughts recurred to the insurance policies that were reposing in the top drawer of the desk at home.

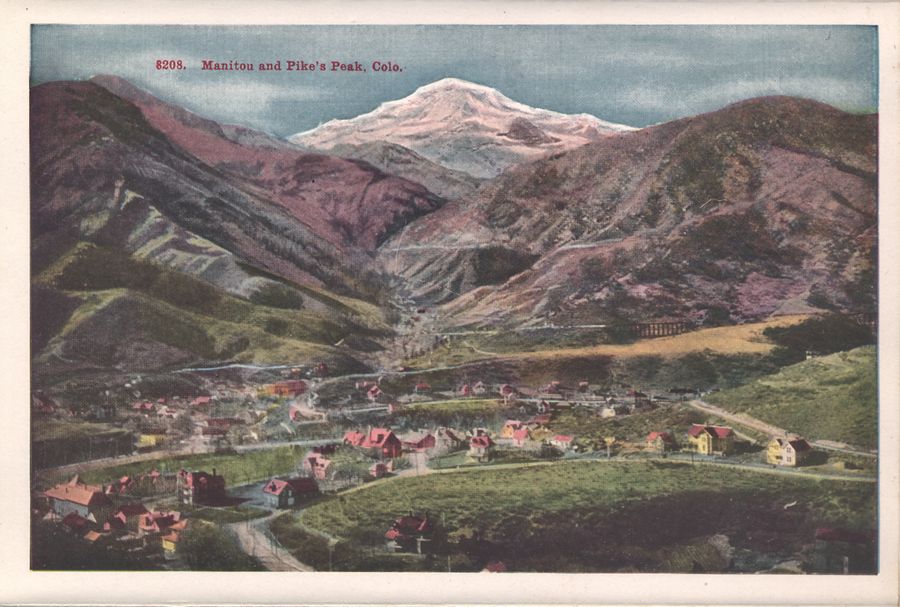

Manitou & Pike's Peak

Manitou & Pike's Peak

As the train whirled on, we caught a sight of Colorado City, the first capital of Colorado, and of the famous "Spa of America," Manitou, nestling in a cleft of the mountains where they first begin to rise from the plains. A little further on and my friend grabbed my arm and cried, "the Garden of the Gods!" with the same air as one might exclaim "the Parthenon!." We gazed out at the gigantic, wind-worn, fantastically-shaped towers and piles of red rock until the train whirled around a curve, and we caught our breath as the first real view of the Rocky Mountains burst upon our view.

"Rocky" mountains they are truly!

Such masses, piles, spires, towers, and chaotic heaps of rocks I had never even imagined. Gigantic trees of pine, fir, and hemlock, as straight as arrows, tapering as spires, and many of them seventy-five and a hundred feet high, towered up from the mountain-side and reared their green tops from the canyon below, through which tumbled, and roared, and rioted, the mountain stream. The beautiful canyon, far beneath us, where we could see many people wandering in the shady glades, was the world-famous Cheyenne Canyon, where Helen Hunt is buried, and which is visited by thousands of tourists every year.

We had little time to gaze down into Cheyenne Canyon, for dashing over trestles and bridges, we emerged from between two rocky walls and Point Sublime burst upon our eyes.

Point Sublime - "in the distance glittered a little crescent-shaped jewel"

Point Sublime - "in the distance glittered a little crescent-shaped jewel"

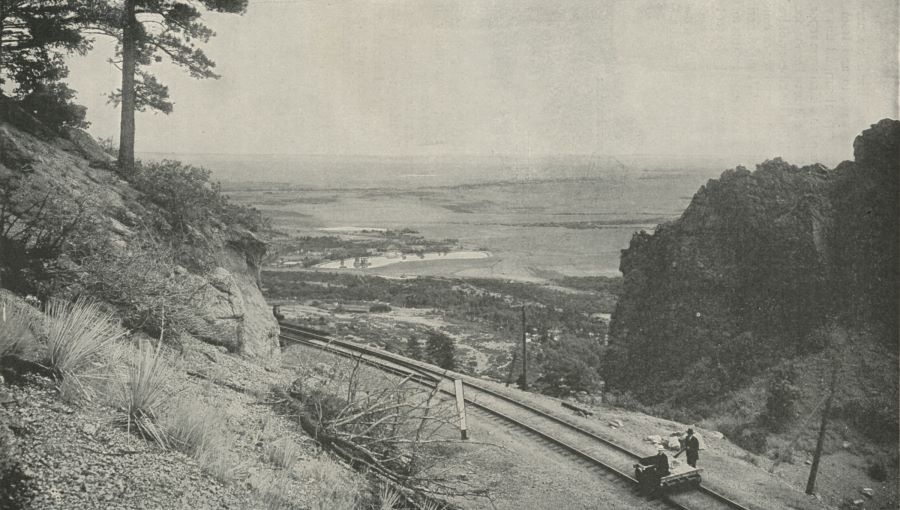

We both cried out, and Elizabeth grasped my hand with a grip like a vise. It is said that this view is one of the most magnificent in the known world, and certainly there are no words which can adequately describe it. Between two vast, rugged, jagged gateways of granite, surrounded by pine trees, and fringed with the sharp daggers of the yucca plant, we looked out upon what seemed at the first glance to be a green and boundless sea. Over and beyond it stretched the deep, intense blue of the Colorado sky, fading into a tender green upon the distant horizon, where sky and ocean seemed to meet.

Over all the picture shimmered a delicate opaline haze, as tender, faint, and illusive as a dream. Far, far below us yawned an apparently bottomless abyss, filled with bristling rocks and crags and waving trees, and away in the distance glittered a little crescent-shaped jewel, which, as we gazed, gradually resolved itself into a lake and, looking closer, we made out the trees and churches and houses of Colorado Springs; and a little further on the lake and pavilion and casino of the popular resort, Broadmoor, and realized with a start that our boundless ocean was no ocean after all, but the green, illimitable prairies, seen from thousands of feet above.

From this point on we played hide-and-find with Colorado Springs and the plains all the way to the summit, the frequent glimpses of the ever-receding view being among the most fascinating incidents of the journey. From Point Sublime the ascent is very rapid. The distant view of the plain is shut out, and the sublimity of the panorama which sweeps past the car windows is indescribable.

Mountains with great patches of snow up on their crests and sides, reared their proud heads before us, only to be gained, and scaled, and left behind. The earth seemed to drop away beneath us, and every moment we came nearer to the sky. We ran close to the edges of fearful chasms, skimmed along mountainsides, thundered over frail-looking trestles, and plunged through the very center of mountains, twisting, turning, and doubling back and forward upon our trail until all sense of direction was lost.

At one time four sections of the track were visible one above another, as looping and turning we wound in and out upon the ascent.

Pike's Peak, which we had always before regarded with awesome veneration, lost something of its sublimity as, climbing nearer and nearer to its level, it gradually flattened out and was left below. Away to the right of us a silvery waterfall plunged down the face of the sheer wall of rock, leaping from boulder to boulder, the spray blowing out upon the wind like a bridal veil, and hundreds of feet below us we looked downward into two stupendous gorges where North and South Cheyenne Canyons meet, and caught a faint, far gleam of white and silver, where the great Seven Falls roar down to the stream below.

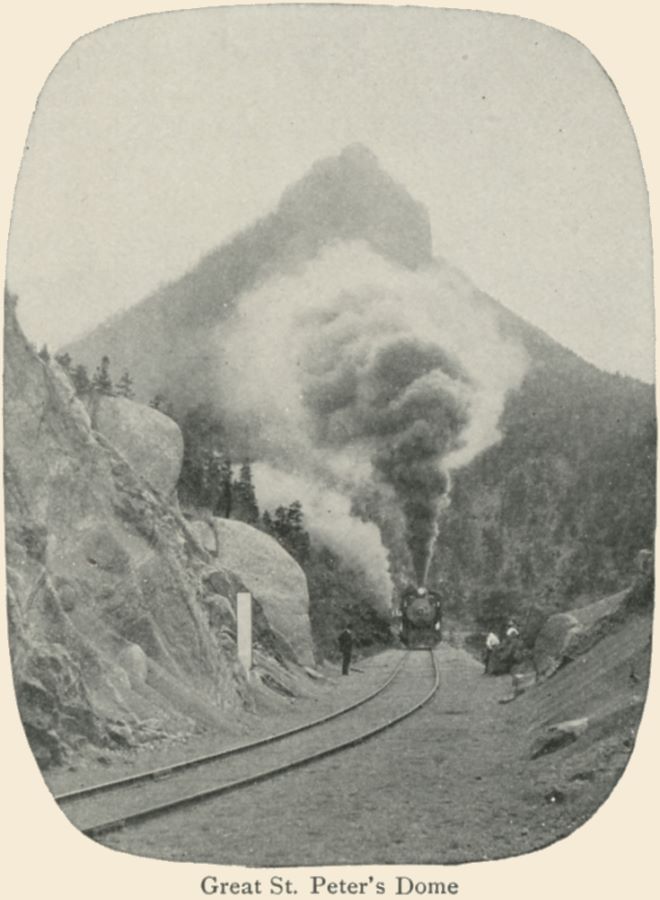

St. Peter's Dome

The mountain peaks, that had been so sharp and high above us, gradually dwindled to mere swelling hilltops, as, still ascending, great St. Peter's Dome came into view. This is a sharp, high peak, which, covered with forests of spruce and pine, and with masses of fleecy clouds tossing and rolling about its summit, is a glorious sight.

This was the last we saw of the beautiful evergreen trees for still rising they began to dwarf and soon disappeared as we got above timber-line.

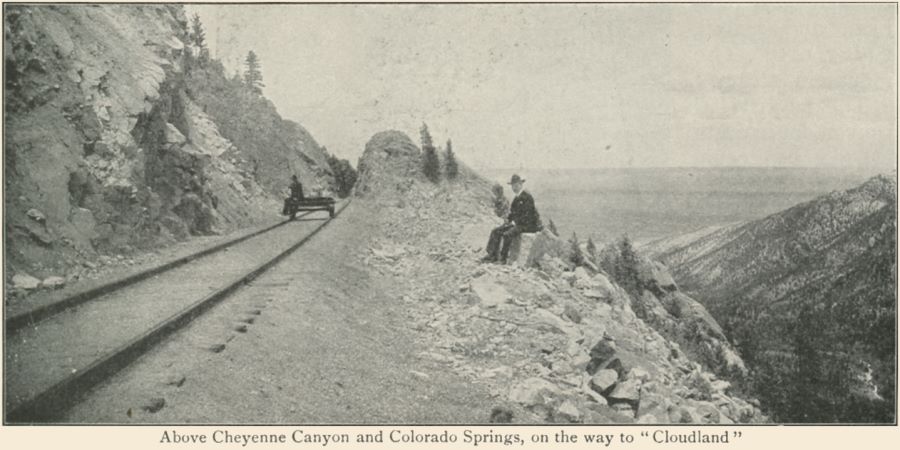

Above Cheyenne Canon and Colorado Springs, on the way to "Cloudland"

Above Cheyenne Canon and Colorado Springs, on the way to "Cloudland"

The canyons had by this time faded into mere little pathways, the trees on the mountainsides below to tiny shrubs, and the mountain stream to a little winding threadof silver. As we thundered over yawning precipices between the mountains the sight was one to appal the stoutest heart, as looking down into the chasm beneath us, the earth seemed to sink further and further away, and floating masses of fleecy, silvery clouds rolled down from the mountain tops and, tinted with every color in the rainbow, spread out below, above, and all about us, shutting us in a mysterious, ghostly world. We no longer seemed to be on the solid earth, but high up in heavens we drifted through a dizzy sea of space.

"It is what we came all the way from New York to see," quavered Elizabeth.

"We are really and truly up in the clouds," said I, my teeth chattering with cold and excitement.

A moment later the wind whirled the clouds aside, and as they rolled away, from a height of 10,000 feet, with nothing above us but the blue sky and the white crest of old Cheyenne, we beheld the Sangre de Cristo Range, snow-covered, pink-hued, and glowing with the rosy color that never fades. In the distance Pueblo, forty miles away to the south, was plainly visible, and off over the prairies rose the smoke of the smelters in Denver.

Once more, and for the last time, Colorado Springs came into view, so distant, so tiny, so far below, that for the first time I got a perfect idea of what a "bird's-eye view" must be.

Just above the summit of the range is Rosemont, a natural park, around which Mount Rosa, Big Chief, San Luis, and a number of other high peaks raise their lofty heads. From that point the road begins to descend, winding and looping in a manner which made us hold our breath and wonder at the temerity of the brain which conceived, and energy which executed, such a piece of work. At one point in the road a fairly good pitcher might throw a ball across the chasm which has cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and months of labor to get around, and which is only crossed after some twelve miles of travel.

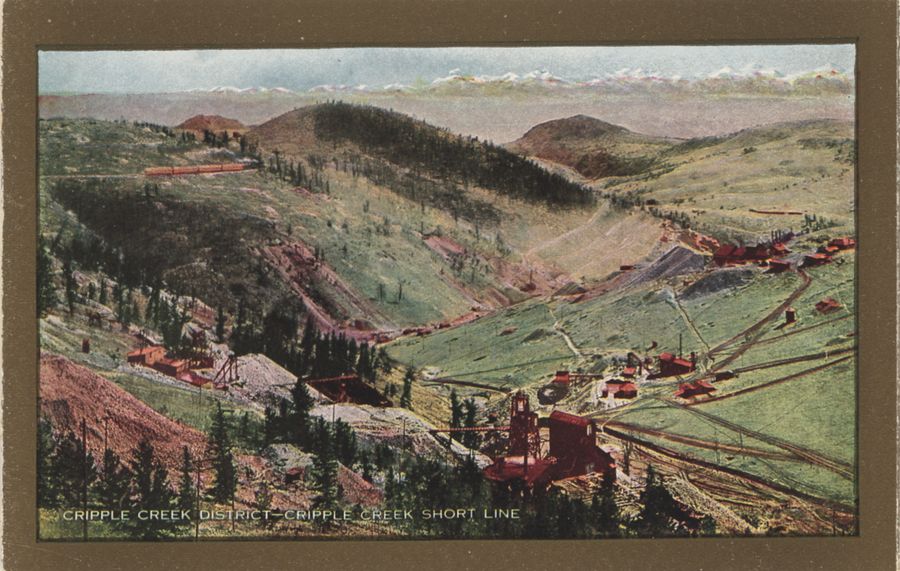

As the descent from the summit begins, the topography of the country is somewhat changed, and soon the sloping, barren mountainsides, gray and desolate, with outcropping rocks of a sort of bluish-white, showed that we were approaching the mining district—the great gold country of the West.

Suddenly, as the train rounded a curve, "Bull Hill" came in sight,and the treasure-field of the Rockies lay before us. The gaunt, gray proportions of the mountain, torn and riven by the covetous hand of man, were outlined against the sky, with not a tree, a shrub, or a blade of grass to relieve the barren monotony.

View from Bull Hill

View from Bull Hill

A little further on, the great mills began to be seen, surrounded by their hills of grayish-white quartz, which, ground and roasted, and robbed of its treasure, had been thrown out upon the dump to return to earth again. Away to the right, a queer little checker-board became outlined on the landscape, which, as we came nearer, gradually resolved itself into the world-famous gold camp of Cripple Creek.

First on one side of the train and then on the other the barren, desolate, box-like little city appeared—that camp from which some of the most fabulous fortunes of the world have come,—as, zigzagging down the mountainside, we slowly drew into the station at Cripple Creek, and the marvelous ride over the Short Line, which we shall always regard as one of the most interesting experiences of our lives, was ended.