-> HathiTrust Digital Library Site; Link to First Page.

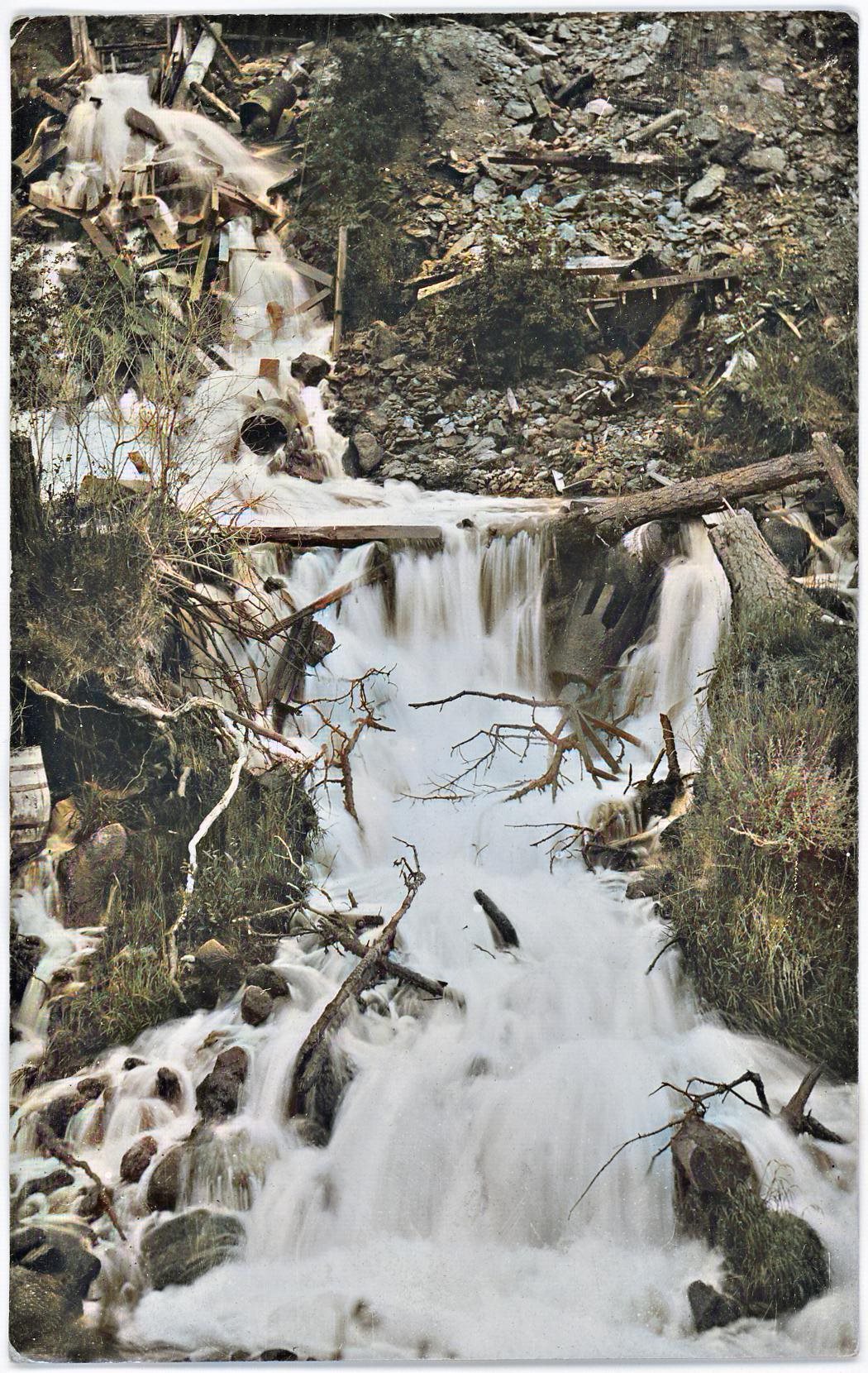

Source had no pics, so I used pics from my collection

The greatest improvement in Colorado to-day, the one venture that will be the most far-reaching in its effects, the one that will give new life and prosperity to our world famous mining camp, is the enterprise which we are here to-day to celebrate - the opening of the Cripple Creek drainage tunnel.

The history of this camp is unique. It was not discovered, nor developed, nor financed by the kings of Wall street. It came into being during a great financial crisis, when capital could not be obtained for any enterprise, no matter how alluring the profits.

Its geological formation was intricate and complex; few understood its mysteries. It was the most American of all mining camps in that it called forth all those rugged characteristics prominent in the Americans who crossed the plains to win from this mountain region the wealth nature has deposited here.

It was American spirit, American energy and American pluck that developed this camp, so that, when the history of Colorado is written you will find in its annals no sturdier group of men than those who had the courage and energy to be pioneers here - Womack, Frisbee, Harman, Doyle, Burns, Stratton, De La Vergne and Castello.

Before the advent of the railroads, placer mining was the leading industry in Colorado. Between 1860 and 1870 not far from $25,000,000 in gold was taken from the stream beds of the state. After the exhaustion of the rich placer deposits attention was directed to lode mining.

The first ores encountered were free milling and were easily handled in crude stamp mills. Later, when refractory ores were encountered and only a small percentage of the known values could be extracted, the mining industry was in danger of extinction.

Scientific knowledge, however, came to its aid, and a smelting plant of twelve-ton capacity was erected at Black Hawk by Nathaniel P. Hill, professor of chemistry in Brown university, Providence, R. I. It began operations in January, 1868, and was successful from the start. The difficulties which had to be surmounted were great. Every single fire brick used in its construction cost a dollar; iron cost 22 cents per pounds; skilled labor was paid $8.00 per day, and unskilled labor $4.00.

The "matte" had to be hauled in wagons to the Missouri river, then taken by railroad to New York, thence shipped to Swansea, Wales, where the gold and silver were refined. So great were the expenses of smelting that in 1878 the ore treated had to produce $100 per ton in order to leave a profit to the miner.

The history of mining and of ore production in Colorado points out one lesson of more consequence than all others. The early problems in mining were simplicity itself, but since 1859 the problems have been growing more and more complex, requiring greater and greater engineering skill.

When only $100 ore could be treated at a profit, vast quantities of lower grades were left in the mines or on the dumps. With improved processes of treatment, with reduced cost of supplies, and with cheaper methods of transportation, the zone of profitable treatment has steadily gone down until even $3.00 ore can be treated at a steady profit.

Such results are only possible by cheap methods of handling due to advanced chemical knowledge. In 1868 the average smelting charges were about $30 per ton. Ten years ago the saving of the values in sulphide ores varied from 50 to 75 per cent, but now the percentage has reached 90, largely because of improved methods of concentration.

The value of the precious metals produced in Colorado during 1906 was $50,386,026. Of this amount four-fifths can be attributed to improved scientific and technical ability. When the precious metals were deposited, Nature paid no heed to the ease or difficulty with which man might recover them. Consequently, each rebellious ore is a problem in itself. It must be studied carefully, diagnosed as a physician would say, until the cheapest and most efficient method of reduction is discovered.

This is a scientific, a metallurgical problem. Millions of dollars could have been saved in Colorado if this simple truth had long ago been driven home.

This camp is still in its youth. Not only is old age far away, but even respectable middle-age is not in sight. It was born only sixteen years ago - in 1891. The child was only sure of its life fourteen years ago.

The production in 1891 was only about two hundred thousand dollars, but what strides it has made in its short life to show in 1906 a production of seventeen millions of dollars, a profit balance of six millions and a total production up to date of two hundred and twenty-five millions. Veritably this is "the richest six square miles in the world."

Is the ore all extracted? Has the camp reached its limit of production?

A thousand times no!

The sturdy American spirit of today, as pronounced as it was in the days of Womack and Stratton, is still in the camp and it has decided that the obstacles of to-day shall be overcome as were the obstacles of fifteen years ago by the pioneers of that day. It is not for the Americans of the Rockies to stand aghast at any obstacle no matter how stupendous it may appear.

Just as the pioneers of the 50s and 60s met and mastered the problems of their day, so we can rest assured that the brain and brawn of this district will conquer, and that the great prizes of permanency, prosperity and wealth - conservatively estimated at two hundred millions in the next decade - will be won.

The two great problems of this district are the scientific treatment of low grade ores and the disposal of water in the mines. There are no more interesting problems in the whole range of the mining industry than these, and on the solution of them rests the future prosperity of Cripple Creek.

With Colorado skill and energy in the contest there can be no question of the final result. Success is already in sight. Far from needing $100 ore in order to show profit, thanks to the cyanide process, even three dollar ore can now be treated successfully.

For general prosperity, for satisfactory returns, not to the stockholders, but to the engineers, the managers, the superintendents, the foremen, and the miners, as well as the merchants, the railroads, and, in fact, to all interested parties all along the line, the low grade propositions give the greatest amount of general prosperity and happiness.

To the solution of the low grade proposition must come the highest chemical and metallurgical skill. This is the problem of the age and Cripple Creek is rising to the occasion.

The other great problem - the one that calls us together to-day - is to unwater the mines so as to get at the ore. With characteristic energy this problem is being attacked and will certainly be solved.

To the layman the solution is simplicity itself - dig a tunnel and let the water run out. But such an enterprise requires in its plan and its consummation the highest engineering skill, to be found only in a man great enough to be not merely the engineer of a single mine but the engineer of the whole district - a prince in his profession - Mr. D. W. Brunton.

This tunnel which he conceived will be, when fully completed, about five miles long and will cost about a million dollars. It will unwater the entire district and will add from 700 to 1,200 feet of additional ore bodies below the present water level.

Will it pay?

Ask the owners of the El Paso, the Elkton, the Portland and the other great mines what ore bodies they now have under water and to what extent production would be increased if this water can be removed.

Their answer is their subscription to defray the cost of this tunnel.

Let us ask ourselves what this particular improvement, this great tunnel, means to us, to the district, to the state and to the nation. It will give new life and energy to all the instrumentalities of the district, it will close the mouths of the "doubting Thomases," those unfortunate creatures whose food is "wormwood and gall" and in whose soul the sun of hope never shines; it will call the attention of conservative eastern capital to the advantages of well established mining as a business; it will show to the world that the engineering, metallurgical and technical problems of mining and ore treatment can be solved, and upon their correct solution depends the stability of the mining industry.

Wherever Colorado is known, be it at the Bank of England, in the busy marts of Berlin or Paris, on conservative State street in Boston, or the "high finance" realms of New York city, there will Cripple Creek be known as the rejuvenated and long-lived gold camp of Colorado.

Of all the great accomplishments in Colorado during the next decade, none will circulate about the world more rapidly, none will redound to her glory more famously, none will make her richer or more prosperous than the completion of this magnificent enterprise - the Cripple Creek drainage tunnel.

*1 An abstract of an address delivered by the author (who was president of Colorado School of Mines at that time) at Cripple Creek on May 11, 1907, at the celebration attendant the inauguration of the driving of the deep drainage tunnel.

_map-drainage-tunnel_web.jpg)