-> My Collection, Also on

-> the Hathi Trust Digital Library Site; Link to article.

Desember 24, 1910

(pages 1251-1252)

Source had no pics, so I added from my collection

We are here tonightN.to help celebrate, starting into successful work the second unit of Stratton's Independence mill. We thus reach an important point, not alone in the history of our own mine, but also in the history of the Cripple Creek district; the pioneer work is accomplished and wet milling of $3 sulpho-telluride ores established as a profitable industry, away up here in the mountains where milling supplies are charged all the traffic will bear.

Most of you have contributed, in one way or another, your knowledge, strength and experience to help obtain this great result; though several of those who started out with us in the summer of 1907, in what was then called by hotel experts and club loungers "the metallurgical impossibility," have moved to other scenes and assumed new responsibilities, while others again are of the "eleventh hour," having but recently joined our ranks and taken up their positions in the mill; to these younger men we look with expectant interest, for new ideas and for renewed energy which may lead to greater efficiency in all departments.

At such a time as this one may be pardoned for pausing in retrospective mood to view again the point from which he journeyed and perhaps push the tentacles of thought out into the uncertain future, to see in vision, as it were, the ultimate metallurgical destiny of wet milling the sulpho-telluride ores of Cripple Creek.

EARLY WORK IN CYANIDATION

Eighteen years ago I first became interested in cyanidation and soon thereafter accepted the position of consulting engineer to the company holding the Mc-Arthur-Forrest patents for America.

I made my initial trip to Deadwood, S. D., to examine into, and advise on unexpected troubles that cropped up in the first cyanide mill built in the Black hills, the ores of which were so favorable to cyanidation; nevertheless, the first mill erected was for a time a failure and but few, if any, foresaw the brilliant future for the cyanide process in that great mining district.

My second trip was to Cripple Creek, where a small cyanide plant had been erected, later called the Brodie mill. This mill failed to give the results expected, as had also the one at Deadwood, and for precisely the same reason.

The ground ore could not be leached. Improved crushing machinery, however, solved the problem in both cases, and the Brodie mill struggled along for some time at a capacity of 15 tons per day, later raised to 30 to 50, and ultimately, I believe, to 100 tons per day.

In the spring of 1894 we had no difficulty in procuring a full supply of ore for the Brodie mill, containing about 1 oz. per ton, for which the mill received $15 per ton treatment charge and needed every cent of it. My connection with this mill, though short, was ample to convince me that cyanidation had a great future in the metallurgy of Cripple Creek ores.

I consequently experimented quite extensively with the telluride ores; worked out, wrote up and published the identical method of treatment now in use at Stratton's Independence mill and proclaimed the cyanide process the most suitable all-round method for treating Cripple Creek ores, a thesis I stoutly maintained with tongue and pen against all comers, until the use of cyanide became universal in the milling of Cripple Creek ores.

INTRODUCTION OF ROASTING

The fall of 1904 found me engaged in building the first large custom mill for the direct cyanidation of telluride ores, while the following year I introduced roasting as an important step in cyaniding sulpho-tellurides.

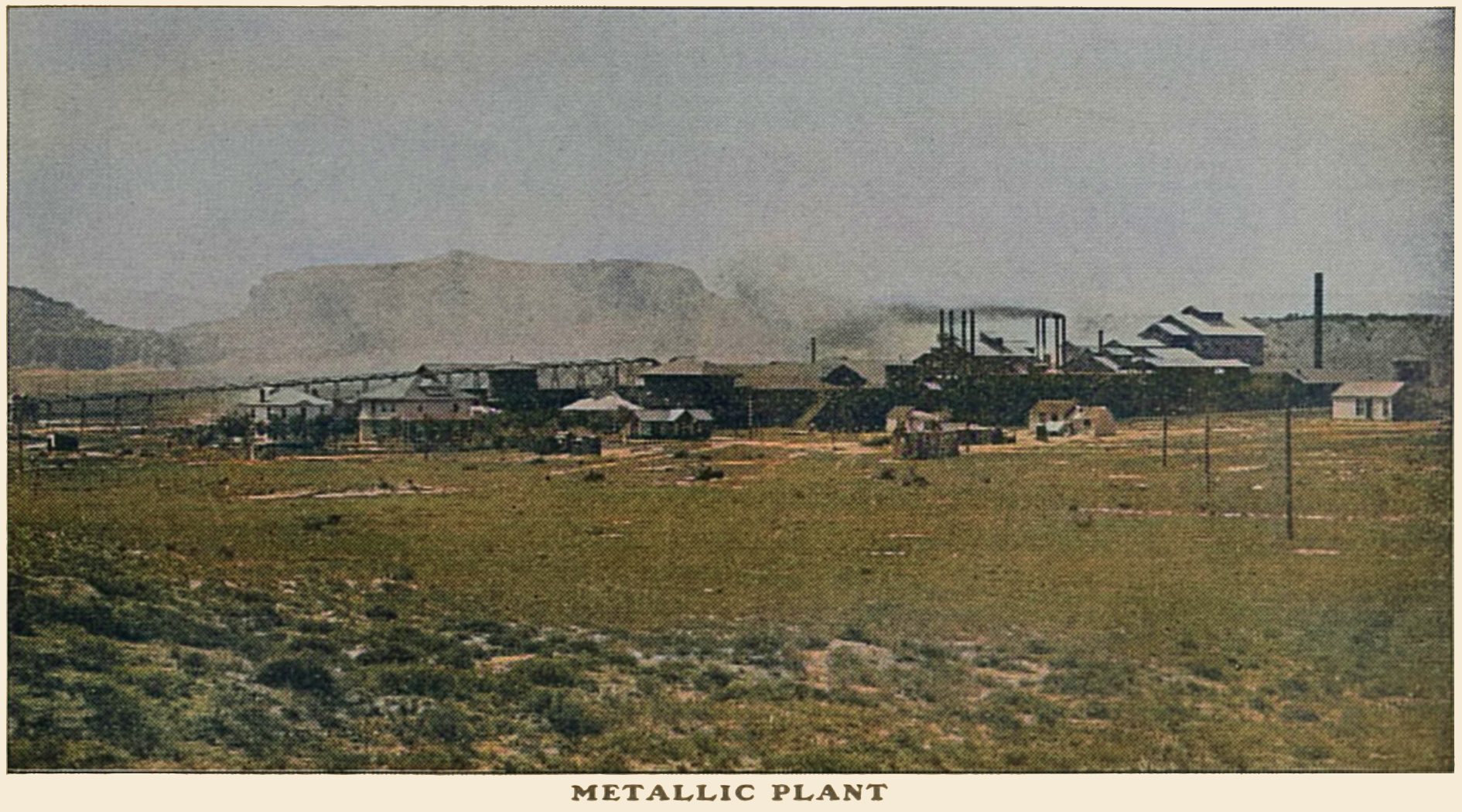

The Metallic works, also a pioneer in Cripple Creek metallurgy, ultimately reached a capacity of 10,000 tons per month and at the close of my engagement, January, 1901, had treated almost half a million tons of Cripple Creek ore, mostly by the roasting process, and had from the first earned good dividends on the investment, and this in the face of a steadily decreasing treatment charge.

From my first connection with Cripple Creek milling to the close of 1900, the average treatment charge had been reduced 50 per cent, and it must be conceded that the works of the Metallic Extraction Company were an important factor in this great reduction.

Were I relating a personal narrative or holding forth on my varied experience in cyanidation, I would next direct your attention to Mexico, to Canada and to other countries. I am, however, merely tracing the progress in cyaniding Cripple Creek ores and incidentally, though briefly, noting my own pioneer work in that connection.

Suffice it to say then, I returned to this field of activity in 1906 and early the following year took up the greatest ore-treatment problem of my life.

To understand it clearly, it might be permissible to say that at the Metallic Extraction Company's works near Florence, where fuel and general supplies were reasonable, the climate mild and water abundant, I had gotten the ore-treatment cost down to what I then considered a low figure.

PROBLEM AT STRATTON'S INDEPENDENCE

The problem involved in Stratton's Independence dump, however, contemplated the profitable treatment of an ore including mining it in the dump and conveying it to the mill - the total value of which was less than our average cost for treating a ton of ore in the Metallic works in the year of grace, 1900.

Here, then, was a problem of some magnitude and I will frankly admit that it was only the quantity available in the dump, something like a million tons, that induced me to tackle the problem at all.

Roasting was, of course, out of the question on account of the cost; so I went back to my old concentration tests of 1894, and found that modern concentrators and fine grinding, then possible, gave encouraging results, a long series of experiments proving to my satisfaction that 35 per cent, of the gold value could be removed as concentrate from average dump ore, and, strange to say, cyanide would extract a similar percentage.

Next came the cost of the method, to determine which I had to draw on previous experience in concentrating and cyaniding on a large scale.

Finally having proved my experimental work in all particulars, I cabled the company, in March, 1907, that a mill of 10,000 tons monthly capacity could treat the dump ore by the proposed method at a cost of $1.50 per ton, obtaining a yield of 70 per cent, of the contained gold.

Those figures, as you know, have been exceeded in actual milling results, and still higher extraction is attainable by finer grinding, but with the present cost of power and supplies is scarcely justified from a commercial point of view.

The method used in our mill—we have never called it a process—is but a combination of well known devices and chemicals to obtain the desired end; we have no secrets, chemical or otherwise, and from the first day the plant has been open to the inspection of metallurgists and all information or data asked for by responsible men have been frankly supplied.

COSTS REDUCED FROM $15 TO $1.50 PER TON

The stride from a $15 per ton milling cost in 1894 to a cost of $1.50 per ton in 1910 is a great and never-to-be-repeated one. Still, I believe the milling of low-grade sulpho-telluride ore is today in its infancy; improvements in machinery and methods will come along as surely as day follows night, making toward higher efficiency, better extraction and lower working cost.

For the straight wet milling of sulpho-telluride ores a $1.25 working cost is now in sight on a basis of treating 10,000 tons per month, while the dollar milling cost is perhaps not far distant and could possibly be attained in a well designed plant treating not less than 15,000 tons per month; in neither estimate, however, is amortization taken into account; they cover only the bare milling and maintenance cost.

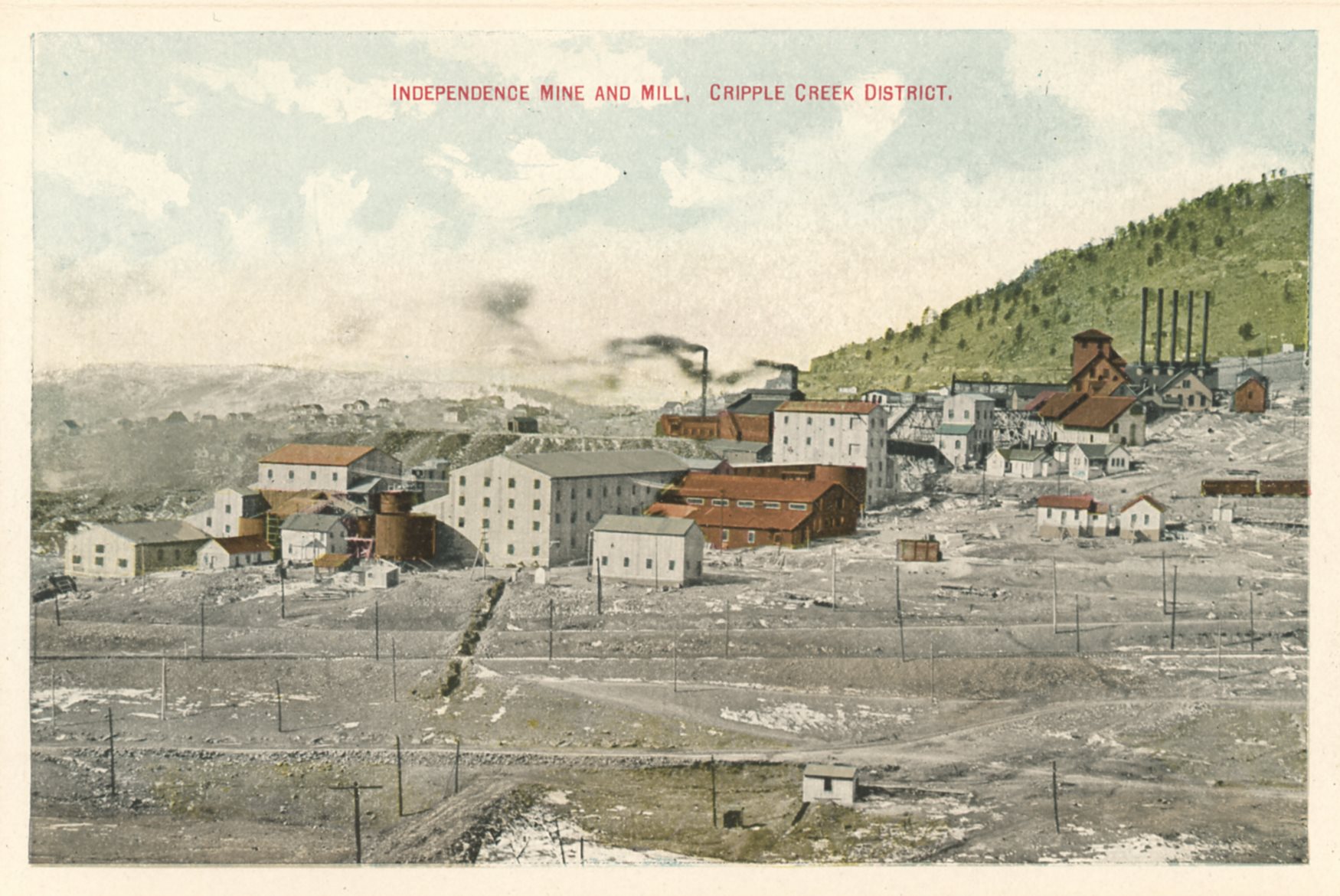

INDEPENDENCE MILL TREATING OLD DUMPS

Stratton's Independence mill, delayed for a time through financial reasons, started up in April, 1909, with a nominal capacity of 4500 tons per month, enlarged in December of that year to 7000 tons, and with the addition of the complete second unit last month, reached a capacity of 9000 tons.

The mill, through the energy and ability of the staff, was profitably operated from the start, and is now earning 10 per cent, per annum on the capital of the company, and has treated to date 120,000 tons of dump rock, sufficient. I believe, to take it out of the class of "metallurgical impossibilities," if not establish it as one of the chief industries of the Cripple Creek district.

We all, more or less, realize what the local milling of the low-grade ores means to Cripple Creek. It does not offer a large or immediate reward to the mine owner, but on the contrary calls for a considerable expenditure of capital; hence, the development of low-grade ore milling must proceed conservatively along the lines of consolidation of small properties or joint milling on a cooperative basis.

Milling the low-grade ores in the district does, however, mean the maintaining of, and possibly an increase in, the output of shipping ore; the prolongation of the life of the camp, I might say, indefinitely; the steady employment of large numbers of men in the mines and mills and the purchase of vast quantities of supplies.

In a word, high-grade production tends to make millionaires; the low-grade, a populous, prosperous and permanent community. The Cripple Creek district will, I hope, continue to give us both.

I believe, gentlemen, you will ever find cause for congratulation in the fact that you were pioneers in this low-grade milling industry. Your work has shown that sulpho-telluride ore can be concentrated, that the tailings from the concentrator can be cyanided and ores running less than $3 per ton can be milled at a profit; and I sincerely thank you for your cooperation and assistance in this great work—second to nothing that has ever been undertaken in the Cripple Creek district—where you blazed the way others can safely follow, successfully copy and, let us hope, in time improve.

VALUE OF AN INTELLIGENT BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Nevertheless. I would not have you forget that great as has been our responsibility and arduous the work, yet I believe the ultimate credit is due to the directors of Stratton's Independence Ltd., who eight years ago, realizing that one-fifth of the production of their mine was finding its way into the ore-house dump, started research work looking toward its recovery: first, by electro-cyanide methods, later by erecting and operating an experimental plant at a cost of nearly $60,000, and experimenting in various ways for fully four years; lastly, sanctioning the expenditure of more than a quarter of a million dollars in the plant we erected and are now operating.

At all times I felt I had in our board real men behind me, gentlemen who supported and encouraged me at every step and who never lost confidence in the ultimate outcome of the undertaking, even when advised by interested people from this district that they were wasting their resources in metallurgical impossibilities.

To these gentlemen is due, then, the full credit for introducing low-grade milling into the Cripple Creek district and it is through their keen business acumen that success has been achieved and that we are here tonight to celebrate it, even at a time when others continue to use their low-grade ore to ballast railways and fill waste places along the right of way.

Much has been said and written of late about the great and little-understood doctrine of conservation, but here is true conservation, the creation of a great and profitable industry from the waste rock of yesterday.

A new era is dawning over the Cripple Creek district, local milling is firmly established by two great mills, the largest ever erected in the district.

This, however, is but the beginning of home treatment, which, I believe, will rapidly expand in the near future and soon cover the entire field.

Cyanogen is king!

NOTE—Address at banquet in celebration of first month's run of the second unit of Stratton's Independence mill.

* Consulting engineer for Stratton's Independence, Ltd. (Philip Argall & Sons, Majestic building, Denver, Colo.)