-> My Collection; No source to show as I've not scanned the Mining Journal as an album.

But, here is a link to the first page on the Hathi Trust Digital Library website.

(page 1068-1069)

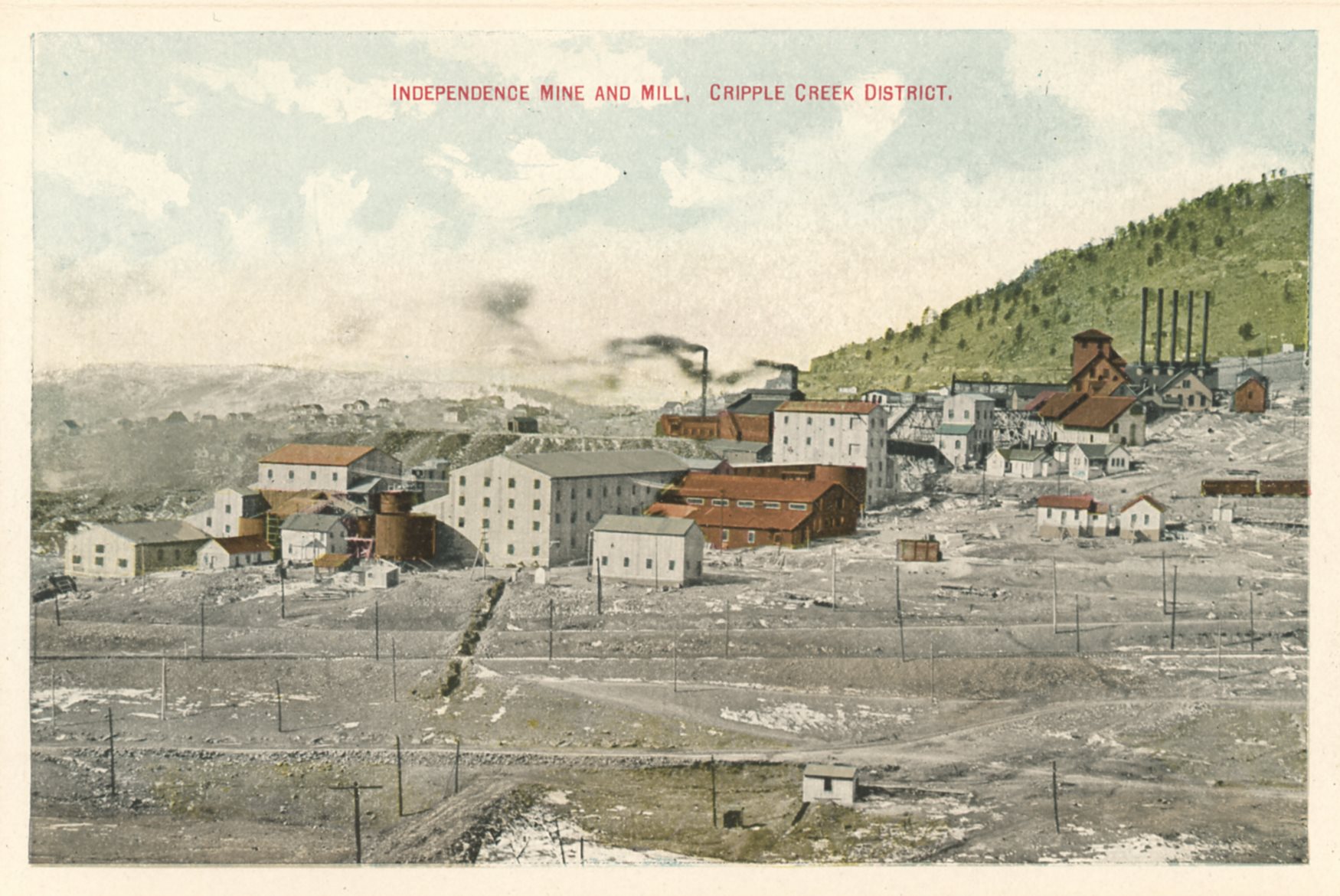

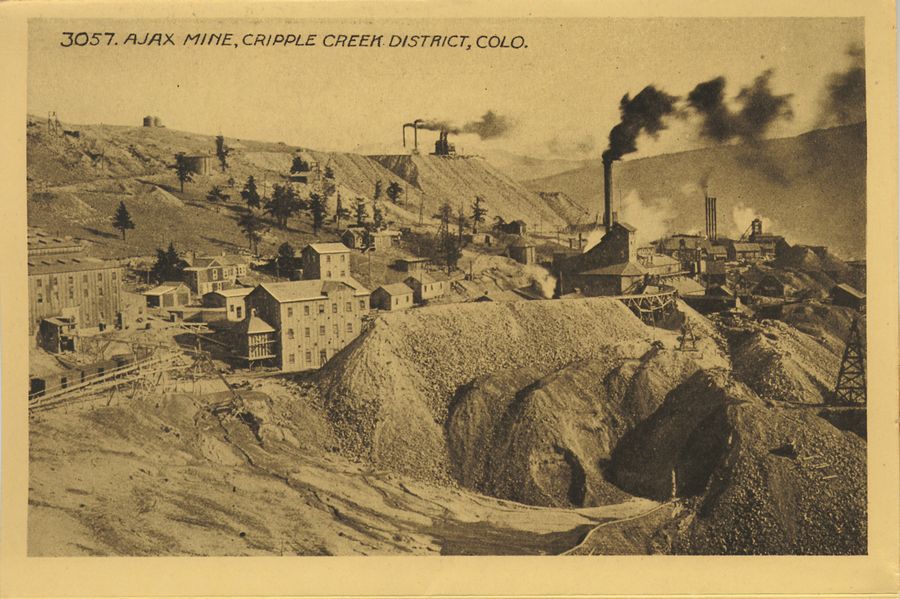

Images used not part of source, but from my own collection.

While the Cripple Creek district is justly noted for the large amount of gold it has produced, especially in its earlier years, it deserves lasting honor as being the scene of important metallurgical achievements.

From the earliest days of the district it has been the practice to sort the ore, shipping the high-grade to mills or smelteries out of the district and sending the waste to the dumps. At present the lower limit of shipping ore is about $10. Thus far it was clear sailing—but what was to be done with the ore running less than $5, which was fast building up the dumps to stupendous proportions?

The ore was of a highly refractory nature for the gold and silver were tenaciously held in a sulphotelluride combination that made treatment by direct cyaniding inefficient. The ore could be made amenable to cyanidation by roasting, but the high cost of fuel made this procedure prohibitive for much of the lower-grade ore.

The first answer to the perplexing question was advanced by Philip Argall, who, after much experimentation, evolved a scheme by which he proposed to make the million-ton dump of Stratton's Independence give up its treasure. His plan, which is the system now used at the mill, provided for crushing and grinding the ore, passing it over concentrating tables, cyaniding the tailings and, toward the end of the process, adding bromocyanide as a further solvent.

By this method the bulk of the refractory minerals and a fair proportion of the precious metals were obtained as concentrates to be shipped to the smeltery at Pueblo, or one of the mills at Colorado City. The record of Stratton's Independence mill for the last fiscal year shows that the ore averaged a little over $3 per ton and a 70 per cent. extraction was made.

A little over a year ago the Portland company started a mill for treating its low-grade ores, likewise employing a combination concentrating and cyaniding method, but substituting for bromocyanide a secret chemical.

Ajax Mill partly outside view left side, Ajax Mine more to the right & Portland Mines in background.

We now have to record the starting of the Ajax mill on still more revolutionary lines, for, by the Moore-Clancy process, which is to be employed, it is proposed to slime the ore, and, without preliminary roasting or concentration, subject it to a combined chemical-electrical process, thereby obtaining the gold and silver in solution. If this process produces the results on a commercial scale that its sponsors claim to have obtained in the laboratory, it may well be hailed as an achievement.

The first two mills mentioned are now acknowledged successes, having demonstrated that "the waste of yesterday is the ore of today." In the early days of each, however, there were not wanting the usual number of "doubting Thomases" ready to predict failure and to pronounce judgment before the mills were fairly adjusted.